Extract from The Guardian

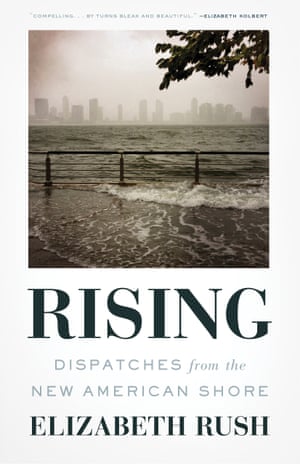

In this extract from Rising, Elizabeth Rush explains ‘sunny day

flooding’ – when a high tide can cause streets to fill with water

I spend the afternoon in Shorecrest, a neighborhood a couple of miles

north of downtown Miami. To get there I leave the beach behind and

drive past Arky’s Live Bait & Tackle, Deal and Discounts II, Rafiul

Food Store, Royal Budget Inn, Family Dollar and Goodwill. As I continue

north, the buildings all lose their mirrored glass and their extra

floors, until most are single story and made from stucco.

It isn’t raining when I arrive in Shorecrest, and there isn’t a storm offshore; the day is as clear and as blue as the filigree on a porcelain plate. But the streets are still full of water. I watch as a woman wades ankle deep across Tenth Avenue. She has gathered her long russet-colored skirt in her right hand, and in her left she holds a pair of Jesus sandals. When she reaches the bus stop, she sits and puts her shoes on.

“We get flooded with just about every high tide,” the woman tells me. “And if the moon is big it’s worse.”

In Shorecrest I spend a minute watching the bay burble up through the street grate and on to Northeast Little River Drive before whipping out my camera and snapping half a dozen photos. Just then a man walks up behind me, peers down, and says: “I’ve seen fish come swimming out.”

“No, you haven’t!”

“I have,” he says, pushing his sunglasses up. “I’ve been here 20 years. When I first moved we used to flood once a year, maybe twice. Now it’s constant.” His name is Robert Cisneros. He grew up in Cuba and moved to Florida in 1962, dropping the final “o” in Roberto. He thought the name change might help his fledgling boat repair company succeed.

It isn’t raining when I arrive in Shorecrest, and there isn’t a storm offshore; the day is as clear and as blue as the filigree on a porcelain plate. But the streets are still full of water. I watch as a woman wades ankle deep across Tenth Avenue. She has gathered her long russet-colored skirt in her right hand, and in her left she holds a pair of Jesus sandals. When she reaches the bus stop, she sits and puts her shoes on.

“We get flooded with just about every high tide,” the woman tells me. “And if the moon is big it’s worse.”

In Shorecrest I spend a minute watching the bay burble up through the street grate and on to Northeast Little River Drive before whipping out my camera and snapping half a dozen photos. Just then a man walks up behind me, peers down, and says: “I’ve seen fish come swimming out.”

“No, you haven’t!”

“I have,” he says, pushing his sunglasses up. “I’ve been here 20 years. When I first moved we used to flood once a year, maybe twice. Now it’s constant.” His name is Robert Cisneros. He grew up in Cuba and moved to Florida in 1962, dropping the final “o” in Roberto. He thought the name change might help his fledgling boat repair company succeed.

I ask if the city is helping the neighborhood come up with short-term solutions. Robert gets upset. “I think they need to raise the street. They need to install pumps. But those kinds of things only happen on the beach. They’re not giving any of us here any relief.”

Like Miami Beach, Shorecrest was built atop a former wetland. On the strip, where billions of dollars in real estate investment are at risk, the government is using a mixture of property taxes and municipal bonds to invest in formal sea level rise adaptation. But in Shorecrest, Hialeah, and Sweetwater – low to middle-income neighborhoods where the majority of residents are people of color – residents are expected to remove their shoes and wade through the water.

Robert shakes his head in disbelief. “I wanted to leave this house to my kids, but soon it’s going to be worthless,” he says. On his stoop sit two pairs of rubber boots, ready for the flood that is already here.

The following Friday I return to the Cox Science Center at the University of Miami. In the parking lot I sit in my rental car as the past decade of storms goes thundering through my mind. I see large waves pulsing into New Orleans’ Lower Ninth Ward. Roiling chocolate milk ripping homes off their foundations in Oakwood Beach, Staten Island. Family cottages in the Rockaways in New York turned into aquariums during Sandy.

I remember walking through the Lower Ninth five years after Katrina. The storm’s eerie language was still clearly legible on one house’s laminate siding: a painted X, its upper quadrant marked to show one dead in the attic. On the next building, a lighter, more haunting X showed two dead on the ground level. Someone had attempted to scrub it away, to remove the memory of the killing wind, the way the water deformed the foundation and window frames, the lives it took.

I start descending the poorly lit staircase to the basement of Cox, where the geology department is – fittingly – located.

The atmosphere down in the office of the department’s chair Harold Wanless, or “Hal”, is more in keeping with my mood. Perhaps it’s also in keeping with Hal, whose decades of research on sea level rise have earned him a reputation for cataclysmic prediction. He is wearing the same taupe suit as the week before. The skin below his eyes is the color of charcoal, and the rest of his face sags, too. Still he manages a smile. Up close it is hard to imagine that the media has nicknamed this good-natured septuagenarian “Dr Doom”.

Hal pushes some of his scattered papers aside so I can set up my recording device. I have my question, just one, prepared: “What single event woke you up to the reality of sea level rise?”

“You know, 20 years ago I never thought I would end up seeing the rise because everything, all the projections at that time, really didn’t ramp up until well into the 21st century. But then I started going out to Cape Sable.” Cape Sable is the southernmost part of the mainland; it reaches into the Florida Bay like a swollen hook. “Out there the beaches were disappearing, mangroves were moving in, tiny channels turned into huge rivers in a matter of years. Even the roseate spoonbills started abandoning their nesting grounds. I had never, in my life of studying the geology of the coast of Florida, seen anything like it. That is when I knew in my gut that the early predictions were wrong and that sea level rise was unfolding a lot faster than any of us ever imagined.”

“What comes next?” I ask.

“We have to start relocating the things we value,” he says. “Like the Smithsonian Institution, which is sited on top of an old marsh. We have to make seed banks, a global archive for the future, and we have to move our power plants, in order to maintain a functioning society. We have to start lining the trash dumps that line our shores, we have to start preparing for inundation. Remember, the last time carbon dioxide levels were the same as they are today, the ocean was one hundred feet higher.”

The last time carbon dioxide levels were this high was during the Pliocene epoch, 2.6 to 5.3 million years ago, when megatoothed sharks prowled the oceans. The last time carbon dioxide levels were this high, the tectonic plates beneath India and Asia collided, forming the Himalayas. The last time carbon dioxide levels were this high, California’s Sierra Nevada rose up and tilted its granite face west. The Alps folded and thrust their splintered rock toward the sky. The last time carbon dioxide levels were this high, armadillos migrated north across a newly formed land bridge between today’s North and South America. Dogs headed in the opposite direction. But no one can remember these things, because humans didn’t exist.

I leave Hal’s office and drive back across the bay. That night the moon is big and full, making the ocean weightier. The salt water unspools in the streets and continues drowning, by degrees, the low-lying land that lines our shore. Soon, I think, if Hal is right, all of this will be underwater, not just temporarily, but for good.

- This is an extract from Rising: Dispatches From the New American Shore (Milkweed Editions)

No comments:

Post a Comment