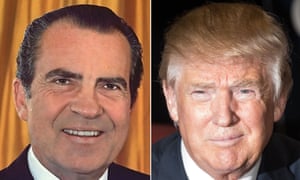

First there were the uncomfortable similarities. Then there were some striking echoes. Now, with the revelation that Donald Trump asked the director of the FBI

to shut down an investigation into his former national security

adviser, the parallels with Watergate are becoming uncanny – and full of

foreboding for the beleaguered president.

Plenty in Washington saw the connection immediately. No sooner had word emerged that in February Trump asked James Comey to shut down an inquiry into Michael Flynn, who had just resigned in disgrace for lying over his contacts with Russia, than former Republican presidential candidate John McCain declared that the Trump scandals were now of a “Watergate size and scale”.

Veterans of that affair know that what did for Richard Nixon was the so-called “smoking gun” tape recording, which showed Nixon ordering that the FBI, who were set to investigate the original break-in at Democratic party offices inside the Watergate building, be called and told, “Stay the hell out of this.” This time the smoking gun appears to be not a tape – though Trump has hinted there may indeed be recordings of his Oval Office conversations – but rather a memo written by Comey straight after his February encounter with Trump. The crucial words from the president to the FBI director: “I hope you can let this go”.

Trump defenders may try to say that that makes this a matter of Comey’s word against the president’s and that such a memo is not reliable. But recall that a contemporaneous note from even the lowest-ranking FBI agent is regarded as credible evidence in US courts – and Comey’s reputation as a truth-teller, whatever the doubts about his political judgment, is pristine. The same cannot be said of Trump. (It’s also clear that this is not the only such memo: Comey appears to have left an assiduous paper trail, guarding himself perhaps against precisely this eventuality.)

What it adds up to is evidence that Trump is guilty of the crime that formed the basis of the impeachment case against Nixon: obstruction of justice (to say nothing of abuse of power). Both men were accused of seeking to block an FBI investigation that was getting too close to home.

Day by day, hour by hour, the pieces are falling into place – together assembling a picture that looks eerily like Watergate. Then, as now, the whole affair originated in a break-in at Democratic HQ: a real one in 1972, a virtual one in 2016, in the form of the hacking of email accounts belonging to campaign staff. Then, as now, the real trouble centred not on the crime itself but rather on the attempt to cover it up – and to thwart those investigators looking into it.

In both cases, an apparent tipping point was a presidential firing of a lead investigator. For Nixon, it was the despatch of the special prosecutor, Archibald Cox. For Trump, it was last week’s sudden sacking of Comey himself.

Plenty in Washington saw the connection immediately. No sooner had word emerged that in February Trump asked James Comey to shut down an inquiry into Michael Flynn, who had just resigned in disgrace for lying over his contacts with Russia, than former Republican presidential candidate John McCain declared that the Trump scandals were now of a “Watergate size and scale”.

Veterans of that affair know that what did for Richard Nixon was the so-called “smoking gun” tape recording, which showed Nixon ordering that the FBI, who were set to investigate the original break-in at Democratic party offices inside the Watergate building, be called and told, “Stay the hell out of this.” This time the smoking gun appears to be not a tape – though Trump has hinted there may indeed be recordings of his Oval Office conversations – but rather a memo written by Comey straight after his February encounter with Trump. The crucial words from the president to the FBI director: “I hope you can let this go”.

Trump defenders may try to say that that makes this a matter of Comey’s word against the president’s and that such a memo is not reliable. But recall that a contemporaneous note from even the lowest-ranking FBI agent is regarded as credible evidence in US courts – and Comey’s reputation as a truth-teller, whatever the doubts about his political judgment, is pristine. The same cannot be said of Trump. (It’s also clear that this is not the only such memo: Comey appears to have left an assiduous paper trail, guarding himself perhaps against precisely this eventuality.)

What it adds up to is evidence that Trump is guilty of the crime that formed the basis of the impeachment case against Nixon: obstruction of justice (to say nothing of abuse of power). Both men were accused of seeking to block an FBI investigation that was getting too close to home.

Day by day, hour by hour, the pieces are falling into place – together assembling a picture that looks eerily like Watergate. Then, as now, the whole affair originated in a break-in at Democratic HQ: a real one in 1972, a virtual one in 2016, in the form of the hacking of email accounts belonging to campaign staff. Then, as now, the real trouble centred not on the crime itself but rather on the attempt to cover it up – and to thwart those investigators looking into it.

In both cases, an apparent tipping point was a presidential firing of a lead investigator. For Nixon, it was the despatch of the special prosecutor, Archibald Cox. For Trump, it was last week’s sudden sacking of Comey himself.

Leaks infuriated Nixon just as they enrage Trump. Key players in the Watergate saga were the White House group known as “the plumbers”, tasked with plugging the maddening series of leaks. Similarly, Comey’s memo shows Trump asking the FBI director to do something about the flow of unauthorised information from his fledgling White House – and, indeed, even suggesting that reporters who use such information should be jailed.

Many assume that a big difference between the two cases is the mood of public opinion. Support for Trump among Republicans remains resilient, while it’s commonly assumed that Nixon was instantly reviled. But polling data shows that, at the time rather than in hindsight, Nixon retained support, even as the end loomed. One month after senate hearings into Watergate began, Nixon enjoyed 76% approval ratings from Republicans (comparable to the 84% Trump scores with Republicans today).

Similarly, while plenty of us despair at the moral weakness of Republican leaders who stand by Trump, it’s worth recalling that many of their counterparts at the time were no less dogged in their loyalty, regardless of the evidence. Among those most stubbornly devoted to Nixon were future presidents George Bush and Ronald Reagan.

And at the centre of both extraordinary sagas is the figure of a volatile, unpredictable president – obsessed by his “enemies”, real and imagined, and callous in his disrespect for the US constitution, which he sees as a barrier to his rightful exercise of untrammelled power.

It ended in disgrace and resignation for Richard Nixon. Such a fate is becoming ever more imaginable for Donald Trump.

No comments:

Post a Comment