Extract from The Guardian

Spending is up. The world has been fighting a war against Covid, and in wartime the power of the state always increases.

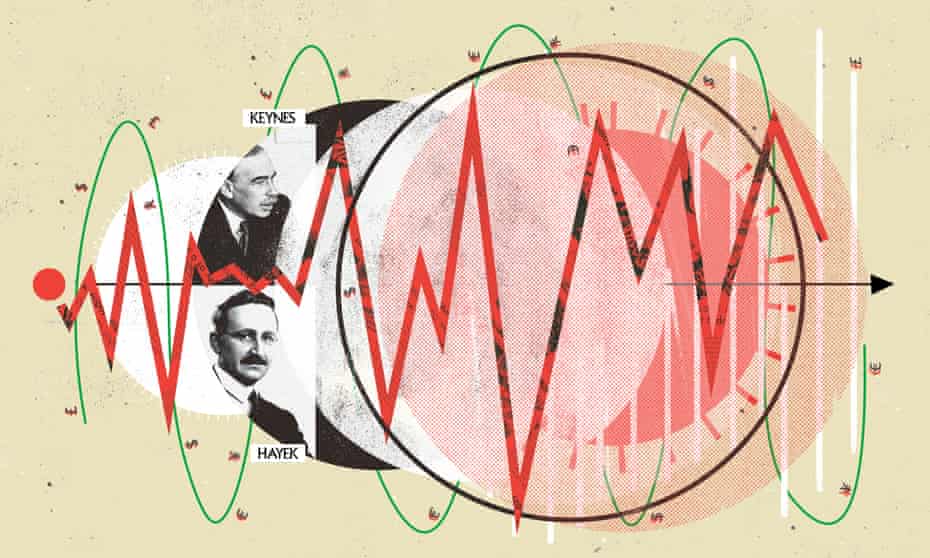

Illustration: Nate Kitch

Last modified on Fri 30 Jul 2021 21.12 AEST

Over the past 18 months, the world has been amazed at how slippery an enemy Covid-19 has proved to be. The virus first detected in China at the end of 2019 has mutated on a regular basis. Vaccines need to evolve because the virus is changing to survive.

The shock to the global economy from the pandemic has been colossal, but things are now looking up – especially for advanced countries. Some are surprised by the pace of recovery, but they perhaps shouldn’t be, because alongside new variants of the virus there has been a new variant of global capitalism.

This matters. For decades the Austrian variant of political economy – the small state, non-interventionist, trickle-down, free-trade, low-tax model based around the ideas of Friedrich von Hayek – was dominant. It replaced the Keynesian variant because in the 1970s a free-market approach was seen as the answer to the challenges of the time: inflation, weak corporate profitability, and a loss of business dynamism.

Not even the biggest fan of capitalism would say it is a perfect system, merely that – so far at least – it has proved more durable than its rivals. And the flexibility to adapt to changing circumstances is a big part of that. The state is now a much more powerful economic actor than it was before the pandemic, much to the disappointment of the free-market thinktanks which are home to Hayek’s disciples.

Change was coming even before Covid-19. In retrospect, the last hurrah for the Austrian variant was the aftermath of the 2008-9 financial crisis, a period when the economic orthodoxy insisted on austerity to balance the books.

The upshot was weak growth, low investment, stagnating living standards and a backlash from voters. Central banks found it impossible to raise interest rates from their rock-bottom levels, because so many people on low incomes were relying on debt to get by, and higher borrowing costs would have tipped them over the edge.

At the other end of the spectrum, corporate and personal taxes were cut, and the rich got richer. The big tech giants, minnows themselves in their early days, used their market power to prevent new startups from posing a threat. Voters started to get the impression that the system only really worked for those at the top: and they were right. The populist backlash was aimed primarily at governments, but the real problem was that capitalism was starting to eat itself.

There were signs of a shift, from the middle of the last decade onwards. Donald Trump was no believer in free trade and was proud to call himself “tariff man”. The unexpectedly strong performance of Jeremy Corbyn at the UK general election in 2017 – with his powerful anti-austerity message – moved the dial too. It led then prime minister Theresa May to pledge an end to the policy. Boris Johnson’s shtick at the 2019 election – and subsequently – has all been about levelling up, not about trickling down.

This process has accelerated since the start of 2020, both at a domestic and global level. Governments of left, right and centre have intervened in their economies in ways that would have been unthinkable two years ago: paying wages for furloughed workers; keeping businesses afloat through grants and loans; preventing landlords from evicting tenants; and generally throwing financial caution to the wind. The world has been fighting a war against Covid, and in wartime the power of the state always increases.

It has not just been about governments spending and borrowing more, though that is part of the story. Fiscal policy – which covers tax and spending decisions – has taken centre stage for the first time since the Keynesian model ran into trouble in the mid-1970s. Central banks have become bit-players, and are having to fend off the accusation that their prime role is to print the money needed to cover the vast sums finance ministries are spending. The European Central Bank, previously tough in acting against the threat of price rises, has said it will tolerate more inflation before raising interest rates.

The race to the bottom on tax is coming to an end. US president Joe Biden has said he will pay for his latest spending plans by raising income tax on Americans earning more than $400,000 (£290,000) a year. At least 130 countries have signed up to plans, put together by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, for a minimum global corporate tax rate. Critics say the proposal doesn’t go far enough, but it is a significant moment nevertheless.

Meanwhile, the International Monetary Fund is telling member governments that they need to tackle the entrenched power wielded by a small number of dominant companies – or risk stifling innovation and investment. The IMF says the tech giants are a case in point because “the market disruptors that displaced incumbents two decades ago have become increasingly dominant players”, and they “do not face the same competitive pressures from today’s would-be disruptors”. But it is not just the tech sector. The IMF says the same trend towards falling business dynamism can be seen across many industries.

The building blocks of new-variant capitalism are already there. Governments are going to tax and spend more, and they will use regulatory powers to weaken monopolies. There will be selective use of nationalisation – as happened with UK defence manufacturer Sheffield Forgemasters this week.

Governments will borrow money to invest in infrastructure projects and to increase the budget for science. Industrial and regional policies will be back in vogue. The idea is to harness the power of the state with the dynamism of the private sector and, as was the case with Keynes, to save capitalism from itself.

There will be pushback, and it would be naive to think otherwise. This is evolution not revolution, and many of the weaknesses of the old order – insecurity at work, for example – remain untouched. Enemies abound. The mixed-economy model is anathema to those who think state intervention is either unnecessary or harmful, and to those who think the demise of capitalism is merely a matter of time.

The new variant of capitalism may prove to be a dud, but for now it has things going for it. These are times that call for a multilateral, collaborative approach, in which rich countries dig deep to help poorer nations, and themselves in the process.

Failings of the old model were exposed in the run-up to the crisis, while the benefits of a more hands-on approach have been demonstrated during the pandemic response. Unsurprisingly, there is appetite for a different way of running the economy. The reason a new variant has emerged is simple: there is a need for something stronger and more resilient than the old model.