Stories from the Archives

Queensland State Archives

The 1891 shearers’ strike is one of Australia’s earliest and most important industrial disputes. The quarrel was primarily between unionised and non-unionised wool workers, and sabotage and violence issued from both sides. The strike is seen as one of the factors that led to the formation of the Australian Labor Party.

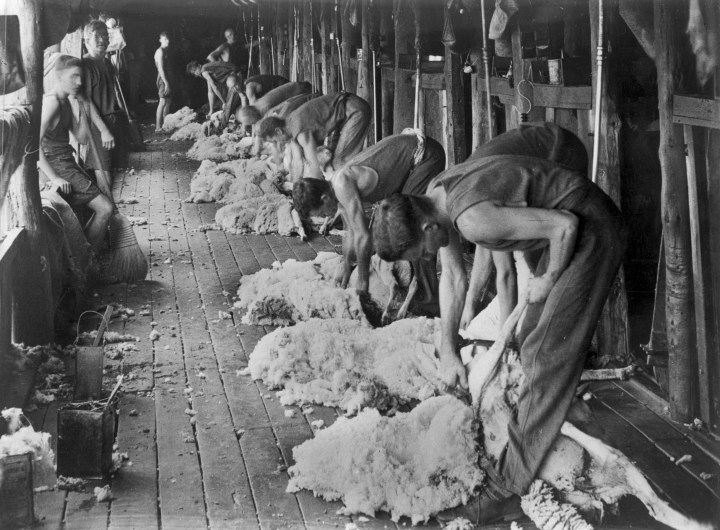

Throughout the 1870s and 1880s, Queensland had enjoyed growth and economic prosperity. During this same period, socialist ideas and the development of various trade unions enabled workers to band together to establish conditions for fair work. Sheep shearers, whose roving lifestyles and key functions in the pastoral industry provided them with formidable bargaining tools, were particularly confrontational in their efforts to achieve fair working conditions.

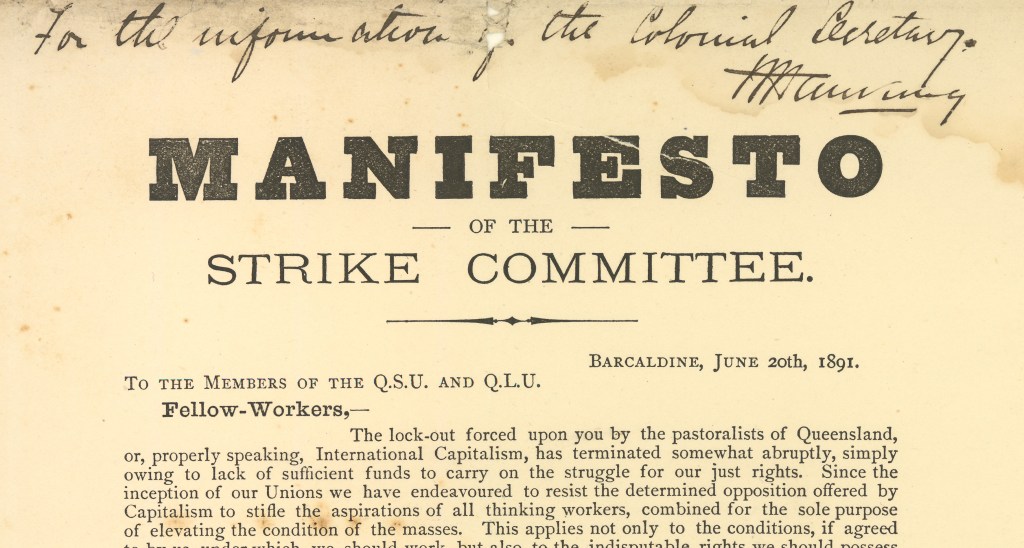

In late 1890, as the international depression caused the price of wool to fall, rural employers drastically reduced wages and entitlements for shearers. On 5 January 1891, the Queensland Shearers’ Union and the Queensland Labourers’ Union gathered in Barcaldine, the centre of a rich pastoral district, to set up a strike committee headquarters. Strike camps were formed throughout Queensland and New South Wales. For months, negotiations between employers and unions were unsuccessful.

In early February, pastoral employers began importing non-unionised free labour by train from Victoria. Strikers intercepted these new arrivals by detaching carriages and even attempted to destroy a railway bridge. The dispute escalated rapidly. Torchlight processions of over a thousand men began in Barcaldine, and on 10 March 1891 the conflict came to a head as nearly 1,500 unionists blocked the railway platform.

Consequently, a military camp was set up near the Barcaldine courthouse and roughly 1,000 military personnel were distributed to monitor strikers’ camps throughout Queensland. Thirteen of the strike’s organisers were arrested in March 1891 and sent to St Helena Island prison for three years hard labour. Following this setback, and with increasingly poor conditions, the strike began to lose momentum. By mid-June, the strike was called off and the defeated unionists went back to work on the pastoralists’ terms.

Although unsuccessful, the legacy of the shearers’ strike lies in the interests of workers becoming part of the political agenda. In 1892, unions met in Barcaldine to form the ‘Workers Political Party’, which later became the Australian Labor Party. Its vision included using parliamentary power to achieve decent working conditions for all. And ever since the days of the 1891 shearers’ strike, workers have come together to demand their right to fair employment.

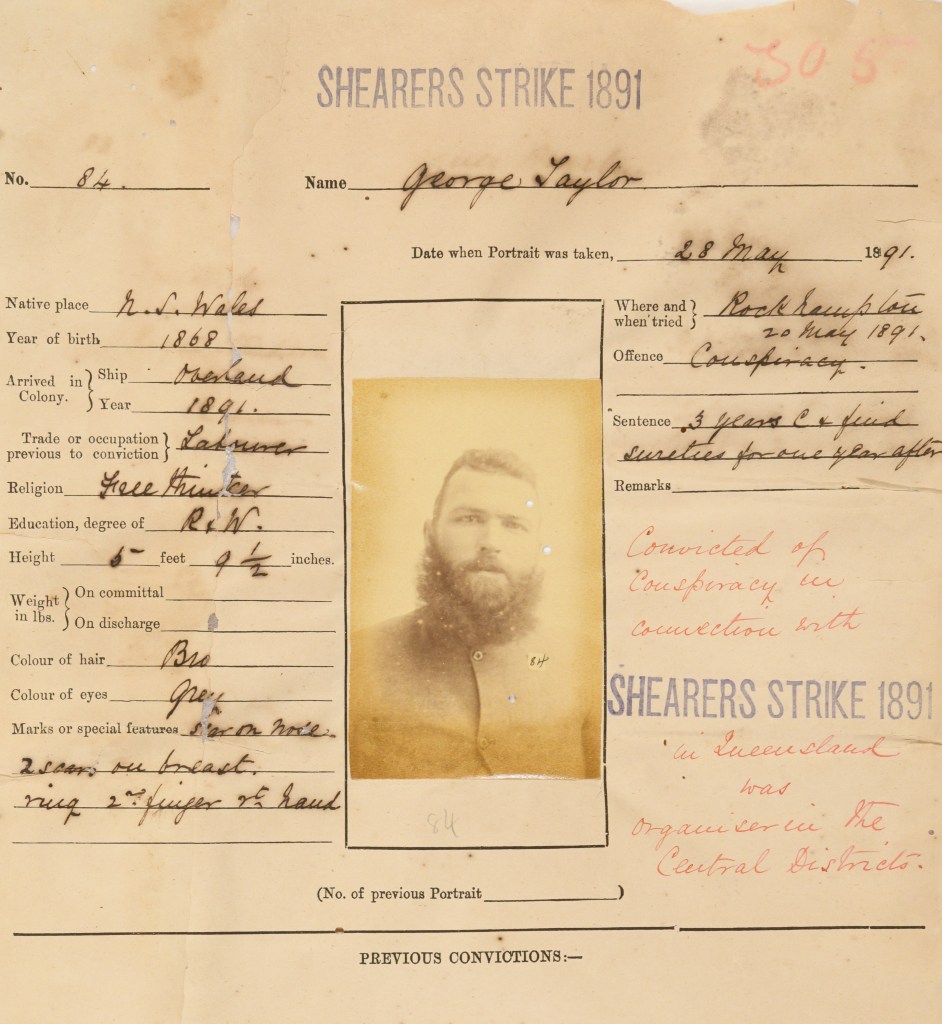

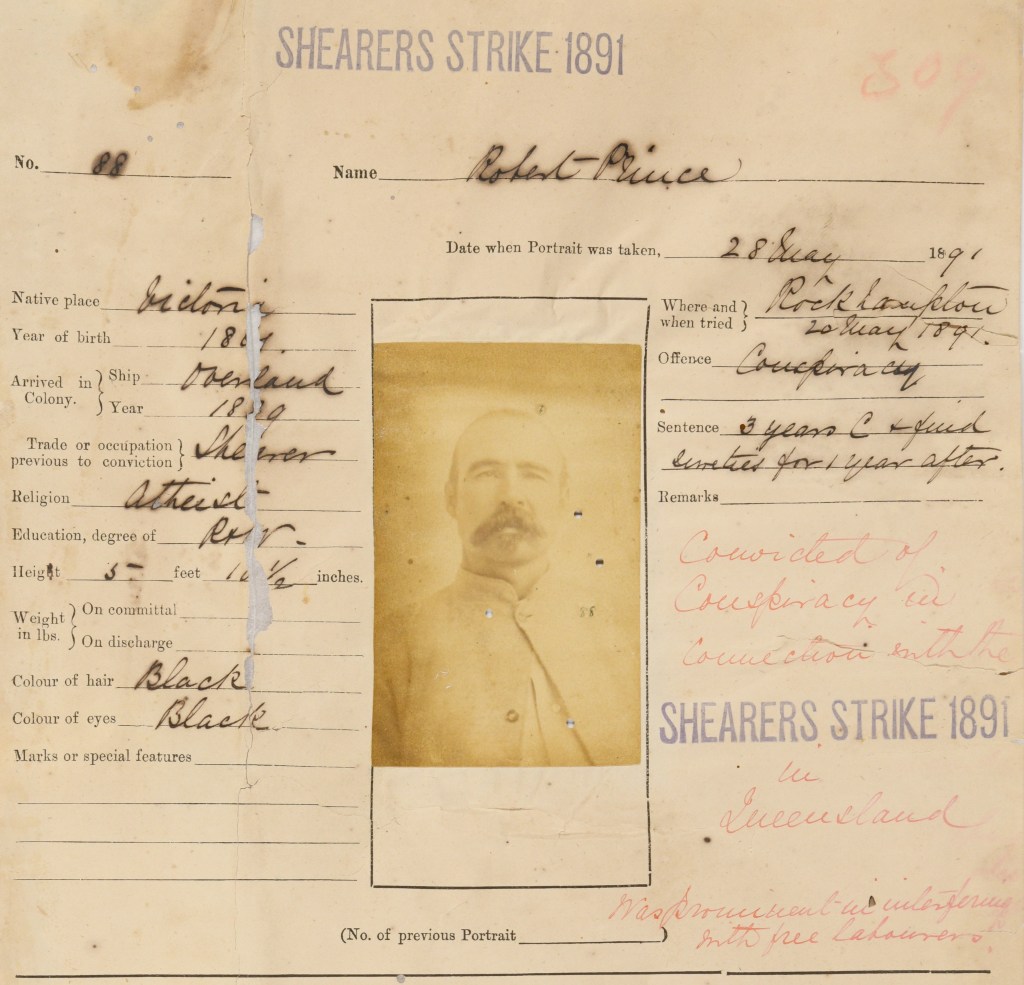

Convicted of conspiracy

They called them snaggers, snappers and learners. In the shearers’ strike of 1891, ‘free labourers’ poured into Queensland under the protection of police troopers.

‘It doesn’t bother us in the least, they would not shear as many sheep in a day as one competent workman’ wrote a unionist.

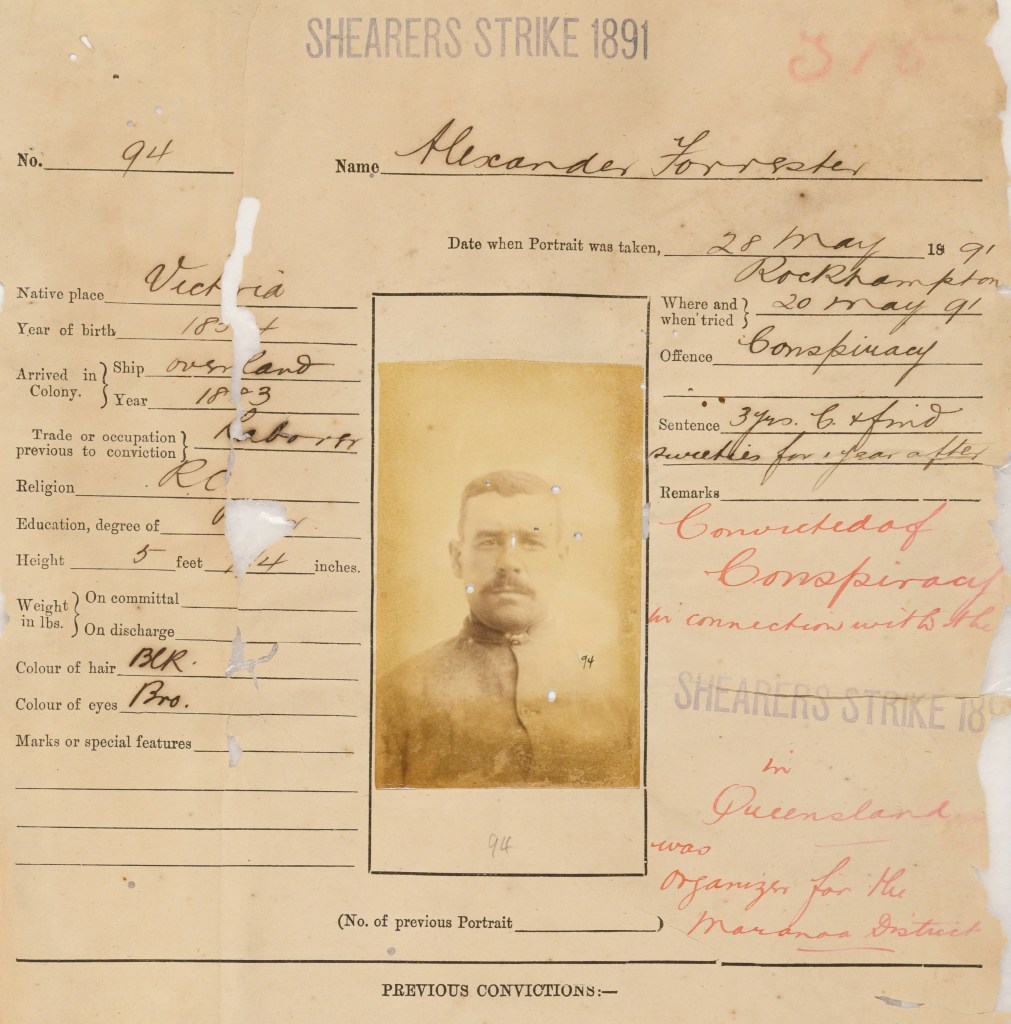

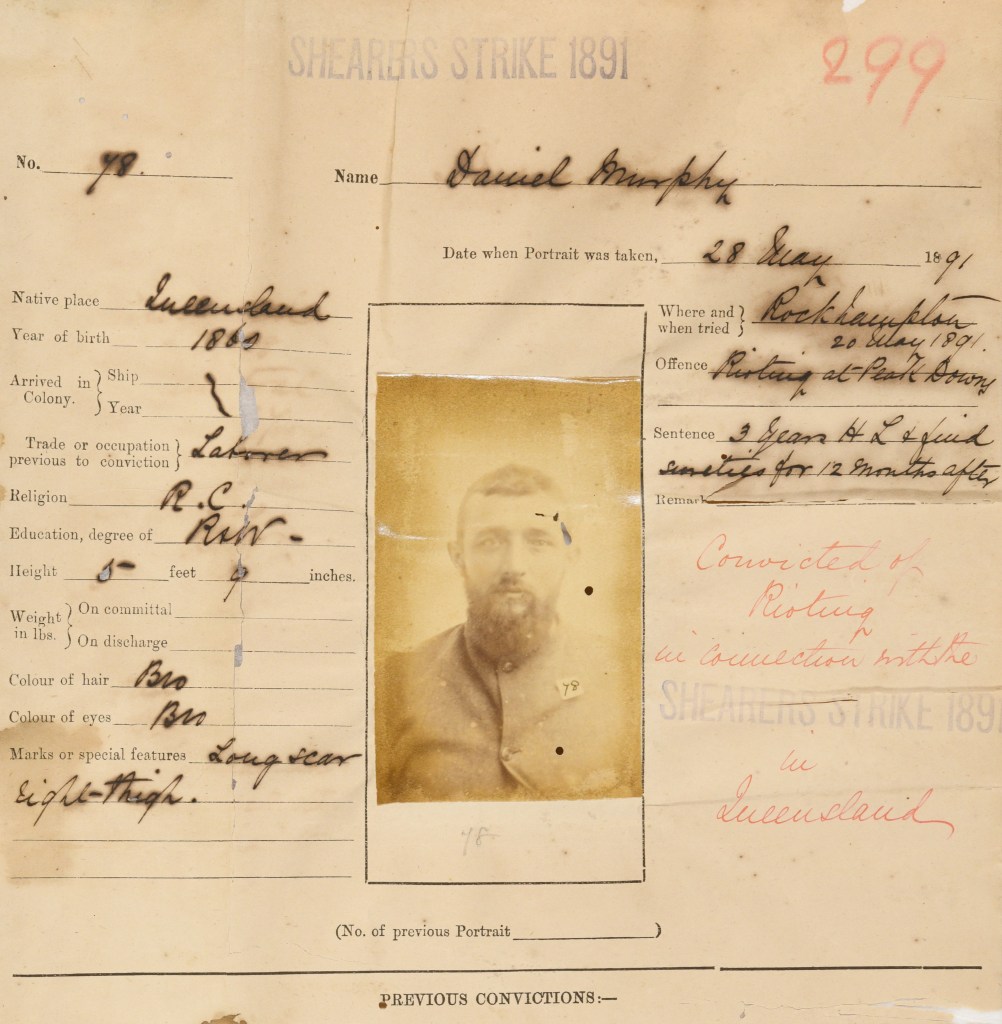

After four long months of rallies, strikes and protests with wealthy squatters about working conditions, it was all over. At 9 o’clock on 26 May 1891, a van drove the conspiracy prisoners from the gaol at Rockhampton to the wharf, where 150 people yelled cheers of encouragement as 21 men boarded the Government steamer Otter and were taken to St Helena Island.

While some shearers had been charged with riotous conduct, unlawful assembling or arson, the leaders were charged with sedition and conspiracy. The statute penalised workers, either as individuals or groups of individuals, for trying to improve their conditions at work. For this crime, they were sentenced to three years imprisonment on St Helena Island, also known as ‘Queensland’s Inferno’.

Strike leader Julian Stuart recalled that shearers’ strike prisoners were taken directly from Rockhampton to St Helena Island ‘because the authorities feared a demonstration.’ As the prisoners arrived, they were brought into the stockade on horse-drawn trams and moved into separate cells. They were then photographed. Each prisoner at St Helena was required to work a trade on the island. William Hamilton worked pipe-claying steps and cleaning windows with the Housemaids Gang, Julian Stuart laid a floor in the pigsty and George Taylor worked in the tailor’s shop.

Cover image: Shearing sheep, Barcaldine District, 1948; ITM1154347

No comments:

Post a Comment