Extract from The Guardian

Major Tim Peake became Britain’s first career

astronaut to make it into orbit – but scientific advances and Pluto

discoveries were even bigger news

Russia’s Soyuz

TMA-19M spacecraft carrying Tim Peake, Russian cosmonaut Yuri

Malenchenko and US astronaut Tim Kopra blasts off from Baikonur.

Photograph: Kirill Kudryavtsev/AFP/Getty Images

Science editor

Saturday 26 December 2015 05.00 AEDT

When the Soyuz rocket carrying Britain’s Tim

Peake blasted

off from Baikonur cosmodrome in Kazakhstan this month, he took

much

of the nation with him. He is not

the first British astronaut and not

even the first from Sussex, but he is the only one ever admitted

to the European

astronaut corps. That makes a difference. As a career astronaut

for the European Space Agency, Peake is uniquely placed to inspire

British children for many years to come. The launch was a

historic moment, but far from the only highlight of 2015.

It was already an exceptional year in space. The

face of Pluto

emerged from the gloom to reveal a dazzling landscape of ridges, ice

mountains and plains of solid nitrogen hundreds of miles wide. Robots

on the ground and in the sky above Mars found ancient water marks and

then evidence that water flows there today, leaving dark streaks on

the walls of craters and gullies. Another probe plunged through

frigid geysers that spray from Enceladus, one of Saturn’s moons :

the vapour propelled by hydrothermal energy in a global ocean under

the surface.

For one group of British scientists 2015 began

with a bittersweet discovery. Images from Nasa’s Mars

Reconnaissance Orbiter revealed the fate of the Beagle 2 spacecraft.

Not

seen since Christmas 2003 when it parted from the European

orbiter, Mars Express, the pictures showed the unmistakable Mickey

Mouse-shaped remains of the little lander. Partially opened, its

outer cover apparently nearby, the images showed how close the budget

mission had come to success. “I had given up on ever knowing what

happened to Beagle. After so many years you think you’ll never

know,” said Mark

Sims, the project’s mission manager at Leicester University.

“It had obviously gone through its whole landing sequence and had

started to deploy itself. When I first saw the images, I thought ‘My

God, it might actually have made it’.”

An artist’s impression of Beagle 2.

Photograph: European Space Agency/PA

Photograph: European Space Agency/PA

It was not the last we heard from Mars. In March,

Nasa drew on the world’s most powerful telescopes to show that the

red planet once hosted a vast,

ancient ocean that covered nearly half of the northern

hemisphere. That Mars had once been warm and damp was nothing new,

but the amount of water was a revelation. The scientists envision the

north of Mars under around 20 million cubic kilometres of water, more

than is found in the Arctic ocean. The huge body of water stood for

millions of years but as the atmosphere thinned the ocean was lost to

space. What remains, a mere 13% of the water, is locked up in the

planet’s polar ice caps.

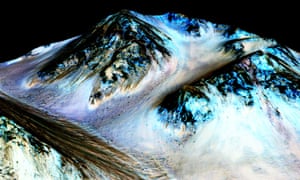

More breathtaking, though, was the finding in

September that there is liquid

water on Mars today. The Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, the same

probe that found Beagle 2, had swung around the planet taking

pictures of strange dark streaks that appeared on crater walls and

canyons during the planet’s summer months. Infrared analyses of the

images found the hallmarks of hydrated salts on the surface, but only

when the streaks were present. It looked a sure sign that liquid

water was either condensing on the surface, or rising up from the

briny reservoirs in the ground.

Hale crater on Mars, showing Nasa’s Mars

Reconnaissance Orbiter signs of liquid water. Photograph: NASA/Getty

Images

Water is regarded as a prerequisite for life, or

at least for life on Earth. The discovery that water flows on Mars

means the planet may, in some parts, harbour niches where microbes

evolved and exist even now. That would be in line with the discovery

of methane

plumes on Mars last year, though chemical reactions on rocks can

release the same gas.ment

The prospect is tantalising but the practicalities

are frustrating. To find life elsewhere would answer one of the

greatest questions of human existence. But there is a glitch.

Planetary protection guidelines say that robotic landers must not

spread Earthly microbes to sites where life might exist on other

planets. Nasa’s

Curiosity rover was not sterilised before launch and so is not

clean enough to venture on to Mars’s damp patches. Nor is its twin,

a rover planned for launch in 2020. It is a quandary that scientists

may work around though. Trundle about on Mars for long enough and the

radiation may kill off any microbes that hitched a ride. Expect more

in 2016.

“It looks more and more like Mars was a very

habitable world three to four billion years ago,” said Monica

Grady, professor of planetary science at the Open University.

“What we don’t really know is: did life develop there? If you

asked me 20 years ago I’d have bet heavily against the possibility

of life. But nowadays we know Mars was a pretty habitable place. The

question is: did it start and did it go anywhere?”

Between Mars and Jupiter, a spacecraft named Dawn

became the first to visit a dwarf planet. At 300 miles wide, Ceres is

the largest object in the asteroid belt. As Dawn approached, two

mysterious

shiny spots became clear on the surface. The nature of the bright

patches sparked a debate among astronomers, with the latest spectral

images from the spacecraft suggesting they are not ice, as some

suspected, but salts.

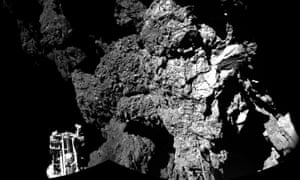

The surface of the 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko comet

as seen from the Philae lander, which stirred back to life this year

after extra sun fell on its solar panels. Photograph: Handout/ESA via

Getty Images

The European Space Agency’s Rosetta

spacecraft, the first to drop a lander on a comet, continued to orbit

the body, sniffing

oxygen in its gas cloud and flying close enough to film its own

shadow on the comet’s surface. The Philae lander which landed not

once, but thrice, fell silent three days after touchdown. But as the

comet neared the sun and more light fell on its solar panels, Philae

stirred to life again, long enough to call Rosetta. The moment

was the highlight of the year for Grady, who works on the Ptolemy

instrument onboard. “It powered up and it could still happen

again,” she said. For now, the comet is too active for Rosetta to

fly close enough to make contact.

Cassini spacecraft image of Saturn’s moons Dione

and Rhea. The distance between Dione and Rhea was roughly 330,000km

(205,000 miles). Photograph: HO/Reuters

Meanwhile, on the sixth moon of Saturn, Nasa’s

veteran Cassini probe went looking for signs

of life. The spacecraft dived

down to Enceladus and passed through geysers that erupt from a

saline

ocean under the surface. Scientists are still analysing the

chemicals detected in the plume. If they turn out to include hydrogen

gas, researchers would have good evidence for hot vents at the bottom

of the moon’s ocean and good reason to consider Enceladus the most

promising place to find life beyond Earth.

Orbiters and rovers have peered and poked at Mars

for a long time. But other corners of the solar system had gone

unexplored until this year. As John

Bridges, a planetary scientist at Leicester University, puts it:

“2015 was the year of the outer solar system.” It was an

important year for images too. For 85 years, the best pictures we had

of Pluto

showed no more than a blurred blob. In July, the US space agency’s

New Horizons probe changed

all that. Barrelling past the dwarf planet on the edge of the

solar system, the spacecraft captured Pluto in all its staggering

beauty.

“It’s opening up our view of the outer solar

system,” Bridges said. “We have this idea of the outer solar

system being this cold, inert place of dust and ice. But the key

thing now, when we get a close-up view, is that there’s geological

activity going on out there.” Inactive planets and moons are pocked

with ancient impacts but active ones look different: the ground is

turned over and refreshed. The Pluto images showed clear signs of

activity in the form of giant regions of smooth, young terrain.

“These are halcyon days for planetary science,” said Bridges.

“There’s no question about that.”

The year produced, a fine demonstration of the

fates of space hardware. In April Nasa crashed its Messenger

probe into Mercury

once it was done mapping the planet. A month later, the Russian cargo

ship, Progress

59, fell back to Earth after going wrong en route to the

International Space Station. In the race to develop a reusable

rocket, Elon

Musk’s SpaceX failed

to land its Falcon 9 rocket on a barge at sea and then succeeded

on land, while Jeff

Bezos’s Blue Origin company landed its New

Shepard rocket at a West Texas launch site. He

made sure the world knew, too.

Elon Musk’s SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket lights up the

sky. Photograph: Craig Rubadoux/AP

With ever more powerful telescopes on the ground

and in space, astronomers added to the haul of thousands of planets

spotted beyond our own solar system. One is Kepler 438b, claimed by

Kepler mission scientists to be the most

Earth-like planet found to date. But the alien world, which lies

470 light years away, is not the most habitable. Intense blasts of

radiation from the planet’s host star are thought to have stripped

the atmosphere, leaving the planet Earth-sized but less than

Earth-like.

The search for life beyond Earth took an

extraordinary turn in October when an astronomer from Penn State

University suggested that strange signals around a distant star might

be the signature of a swarm

of alien “megastructures” in orbit around the planet. In

December the possibility, which was seriously speculative from the

start, was dealt a blow. Scientists dedicated to the search for

extraterrestrial intelligence (Seti) used an observatory in Panama to

look for signs of life around the star and found

none.

Those impatient for contact with alien life should

not lose heart though. The world’s

most comprehensive search for ET begins in earnest in January

with backing from Yuri Milner, the Russian internet billionaire.

Backing the launch earlier this year, Stephen Hawking said: “Mankind

has a deep need to explore, to learn, to know. We also happen to be

sociable creatures. It is important for us to know if we are alone in

the dark.”

No comments:

Post a Comment