Extract from The

Guardian

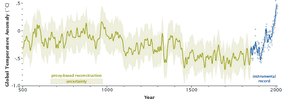

Records of temperature

that go back far further than 1800s suggest warming of recent decades

is out of step with any period over the past millennium

The sun sets beyond

visitors to Liberty Memorial as the temperature hovers around 100F in

Kansas City, Missouri, last month. Photograph: Charlie Riedel/AP

Tuesday

30 August 2016 20.00 AEST

The

planet is warming at a pace not experienced within the past 1,000

years, at least, making it “very unlikely” that the world will

stay within a crucial temperature limit agreed by nations just last

year, according to Nasa’s top climate scientist.

This

year has already seen scorching heat around the world, with the

average global temperature peaking

at 1.38C above levels experienced in the 19th century,

perilously close to the 1.5C limit agreed in the landmark Paris

climate accord. July was

the warmest month since modern record keeping began in 1880,

with each month since October 2015 setting a new high mark for heat.

But Nasa said

that records of temperature that go back far further, taken via

analysis of ice cores and sediments, suggest that the warming of

recent decades is out of step with any period over the past

millennium.

Proxy-based

temperature reconstruction. Photograph: Nasa Earth Observatory

“In

the last 30 years we’ve really moved into exceptional territory,”

Gavin Schmidt, director of Nasa’s Goddard

Institute for Space Studies, said. “It’s unprecedented in

1,000 years. There’s no period that has the trend seen in the 20th

century in terms of the inclination (of temperatures).”“Maintaining

temperatures below the 1.5C guardrail requires significant and very

rapid cuts in carbon dioxide emissions or co-ordinated

geo-engineering. That is very unlikely. We are not even yet making

emissions cuts commensurate with keeping warming below 2C.”Schmidt

repeated his previous prediction that there is a

99% chance that 2016 will be the warmest year on record,

with around 20% of the heat attributed to a strong El Niño climatic

event. Last year is currently the warmest year on record, itself

beating a landmark set in 2014.“It’s the long-term trend we have

to worry about though and there’s no evidence it’s going away and

lots of reasons to think it’s here to stay,” Schmidt said.

“There’s

no pause or hiatus in temperature increase. People who think this is

over are viewing the world through rose-tinted spectacles. This is a

chronic problem for society for the next 100 years.”Schmidt is the

highest-profile scientist to

effectively write-off the 1.5C target, which was adopted at

December’s UN summit after heavy lobbying from island nations that

risk being inundated by rising seas if temperatures exceed this

level. Recent research

found that just five more years of carbon dioxide emissions

at current levels will virtually wipe out any chance of restraining

temperatures to a 1.5C increase and avoid runaway climate change.

Temperature reconstructions

by Nasa, using work from its sister agency the National Oceanic

and Atmospheric Administration, found that the global temperature

typically rose by between 4-7C over a period of 5,000 years as the

world moved out of ice ages. The temperature rise clocked up over the

past century is around 10 times faster than this previous rate of

warming.The increasing pace of warming means that the world will heat

up at a rate “at least” 20 times faster than the historical

average over the coming 100 years, according to Nasa.

The

comparison of recent temperatures to the paleoclimate isn’t exact,

as it matches modern record-keeping to proxies taken from ancient

layers of glacier ice, ocean sediments and rock.Scientists are able

to gauge greenhouse gas levels stretching back more than 800,000

years but the certainty around the composition of previous climates

is stronger within the past 1,000 years. While it’s still difficult

to compare a single year to another prior to the 19th century, a Nasa

reconstruction shows that the pace of temperature increase over

recent decades outstrips anything that has occurred since the year

500.Lingering carbon dioxide already emitted from power generation,

transport and agriculture is already likely to raise sea levels by

around three feet by the end of the century, and potentially

by 70 feet in the centuries to come. Increasing temperatures

will shrink the polar ice caps, make large areas of the Middle East

and North Africa unbearable to live in and accelerate what’s known

as Earth’s “sixth

mass extinction” of animal species.

The CCA report, to be released on Wednesday, lands exactly on the spot where the major parties might, just might, be able to reach a compromise and finally end the barren years of climate policy “war”, policy reversal and time-wasting gridlock.

Guardian Australia understands the report recommends a type of emissions trading scheme for the electricity sector where generators are penalised for polluting above an emissions-intensity baseline.

It’s the policy Labor took to the last election and exactly what most observers assumed the Coalition’s Direct Action would morph into after next year’s review shows what everyone already knows, that it isn’t fit for purpose in its current form.

The CCA is also understood to recommend a strengthening of the current “safeguards mechanism” for other big polluters.

The dissenters argue the authority is supposed to make recommendations based on what is scientifically necessary and leave it up to the politicians to make the political compromises – and that the recommended policy cannot meet the increasingly ambitious greenhouse gas reductions that Australia agreed to in Paris last year.

They are probably right.

But over the past decade the undeniably necessary task of doing our part to avert global warming has become ever-bigger and the politically-possible solutions seem to have shrivelled. We’ve actually done very little.

The new energy and environment minister, Josh Frydenberg, started out in his new job saying Direct Action needed no change at all because it was “very successful”. An authority report pushing for change – backed by board members mostly appointed by the Coalition – could help make the case that that starting point was never tenable.

The last time a politically possible policy was defeated because it wouldn’t achieve the scientifically-necessary greenhouse gas cuts was when the parliament voted down Kevin Rudd’s emissions trading scheme. And that started the long and sorry story that led us here.