Extract from The Guardian

Wide-scale disruption from warming oceans is

increasing, but they could change our understanding of the climate

The Pacific coast has

witnessed record numbers of dead Cassin’s auklets this winter.

Photograph: D. Derickson/COASST

Monday 15 August 2016 06.20 AEST

First seabirds started falling out of the sky,

washing up on beaches from California to Canada.

Then emaciated and dehydrated sea lion pups began

showing up, stranded and on the brink of death.

A surge in dead whales was reported in the same

region, and that was followed by the largest ever toxic algal bloom

seen along the Californian coast. Mixed among all that, there were

population booms of several marine species that normally

aren’t seen surging in the same year.

Plague, famine, pestilence and death was sweeping

the northern Pacific ocean between 2014 and 2015.

This chaos was caused by a single massive

heatwave, unlike anything ever seen before. But it was not the sort

of heatwave we are used to thinking about, where the air gets thick

with warmth. This occurred in the ocean, where the effects are

normally hidden from view.

Nicknamed “the blob”, it was arguably the

biggest marine heatwave ever seen. It may have been the worst but

wide-scale disruption from marine heatwaves is increasingly being

seen all around the globe, with regions such as Australia seemingly

being hit with more than their fair share.

It might seem strange given their huge impact but

the concept of a marine heatwave is new to science. The term was only

coined in 2011. Since then a growing body of work documenting their

cause and impact has developed.

Coral on reefs around Lizard Island, on the Great

Barrier Reef in Australia in July 2016, following the worst mass

bleaching event in recorded history Photograph: Justin

Marshall/University of Queensland

According to Emanuele Di Lorenzo from the Georgia

Institute of Technology, that emerging field of study could not only

reveal a hitherto underestimated source of climate-related chaos, it

could change our very understanding of the climate.

The eye of the storm

On the other side of the Pacific from “the

blob”, Australia has been buffeted by a string of extreme marine

heatwaves. This year at least three parts of the coast have been

devastated by extreme water temperatures.

Australia, it seems, could be smack in the middle

of this global chaos. According to work

published in 2014, both the south-east and south-west coasts are

among the world’s fastest warming ocean waters.

“They have been identified as global warming hot

spots,” says Eric Oliver, an oceanographer at the University of

Tasmania. “The seas there are warming fast and so we might expect

there to be an increased likelihood or increased intensity of the

events that happen there.

“Certainly attention is being focused on ocean

changes on the south-east and south-west of Australia.”

A field born in the death of a forest

It was in

the study of a marine heatwave in southwest Australia that the

term was coined just five years ago. In

a report that still used the term “marine heatwave” in scare

quotes, scientists from the West Australian department of fisheries

found the heatwave off the state’s coast was “a major temperature

anomaly superimposed on the underlying long-term ocean-warming

trend”.

That year, the researchers found, Western

Australia had an unprecedented surge of hot water along its coast.

Surface temperatures were up to 5C higher than the usual seasonal

temperature. The pool of warm water stretched more than 1,500km from

Ningaloo to the southern tip of the continent at Cape Leeuwin, and it

extended more than 200km offshore. Unlike a terrestrial heatwave that

will normally last a couple of weeks at most, this persisted for more

than 10 weeks.

But five years later the full impact of that

marine heatwave have are beginning to be more fully understood.

Thomas Wernberg, an ecologist from the University

of Western Australia, examined the impact on the gigantic kelp

forests that line the western and southern coast of Australia,

publishing

his results in the prestigious journal Science.

“It got so hot that the kelp forests died,”

Wernberg says. For hundreds of kilometres, magnificent kelp forests

that line the coast and support one of the world’s most biodiverse

marine environments simply died in the heat

But it wasn’t just their death that was the

problem. While heatwaves on land can kill and destroy large sections

of terrestrial forests – usually by allowing fires to spread –

those trees normally grow back. What was disturbing about this marine

heatwave was that many of the vast underwater forests never came

back. The warming climate created changes that meant the kelp didn’t

recover. About 100km of kelp forests just disappeared, probably

forever.

Aerial footage of ‘unprecedented’ mangrove

die-off in the Gulf of Carpentaria in Australia. The die-off is

thought to be a result of low rainfall and warm temperatures.

Photograph: Professor Norm Duke/James Cook University

“At the same time, there was a range extension

of tropical and subtropical fish that love eating seaweed. So that

basically means that, even when the temperatures came down, the kelp

couldn’t recover – there was a range extension of the herbivorous

fishes that were eating the kelp.”

In the place of the kelp forest, Wernberg found

coral was starting to emerge. It was as if the heatwave in 2011

bulldozed the area, making way for a shift in the ecosystem that

climate change was already trying to impose.

“It is probably too early to say if this will

eventually lead to new coral reefs,” Wernberg says. “However,

this is how I imagine the process would start.”

Wernberg estimated those kelp forests were

directly responsible for sustaining rock lobster and abalone

fisheries, as well as a tourist industry, together worth $10bn. If

they were lost, it would be a serious problem for Australia, not to

mention for the animals that rely on them.

Wernberg says the kelp forests in Western

Australia were likely to keep contracting. “I think the next big

heatwave is just going to push what we see in the north ultimately

further down and then it just depends on how bad that heatwave is,

whether we go all the way down to Perth or whether we just go another

10km,” he told

the Guardian when the study first came out.

2016: the year of marine heat

In 2015 Wernberg established a working group of

biologists, oceanographers and climate scientists in Australia to

examine marine heatwaves. He saw it as an exciting new field of

study.

That was timely, as less than a year later

Australia would find itself virtually surrounded by pools of warm

water that caused widespread and unprecedented destruction.

They were spurred on by a large El Niño, which

spreads warm water across the middle of the Pacific Ocean. But El

Niños had been seen before and these marine heatwaves appeared to be

unprecedented.

Perhaps most dramatically, 2016 saw the Great

Barrier Reef blasted by a marine heatwave that killed

22% of the coral there in one fell swoop. In the pristine

northern sections, about half the coral is thought to have died.

The hotter water that bathed the reef has now

subsided but the full damage is still being tallied. The immediate

death of the coral is one thing but the after effects are starting to

be seen, with a decline in fish numbers being reported.

And, unusually, there is continued

bleaching in parts of the reef, even now as the southern

hemisphere moves past the middle of winter.

Justin Marshall, of the University of Queensland,

has been studying the reef ecosystem around Lizard Island in the

remote northern part of the Great Barrier Reef and warns that there

appears to be “complete ecosystem collapse” there.

He doesn’t have the final numbers from the

surveys he is conducting but he says there are easily half as many

fish there after the bleaching as there were before, and there are

some species that were common before that are completely missing now.

Marshall says that could be the beginning of a

“regime shift” there – where the once magnificent and resilient

coral is replaced permanently by a bed of seaweed.

But as if disappearing coral reefs and kelp

forests aren’t enough for one country, a marine heatwave in

Australia in 2016 was also responsible for an unprecedented mangrove

die-off.

On the other side of Cape York from the Great

Barrier Reef, a related heatwave in the Gulf of Carpentaria spurred

along what one expert studying said was the worst

mangrove die-off seen anywhere in the world.

After hearing reports of the mangrove die-off,

Norm Duke, an expert in mangrove ecology from James Cook University,

got a helicopter and flew over 700km of coastline, to see what was

happening.

He says he was shocked by what he saw. He

calculated dead mangroves now covered a combined area of 7,000

hectares. That was the worst mangrove mass die-off seen anywhere in

the world, he says.

“We have seen smaller instances of this kind of

moisture stress before but what is so unusual now is its extent, and

that it occurred across the whole southern gulf in a single month.”

Duke is assessing the precise structure of the

die-off to figure out what the exact drivers were. By examining

exactly which mangroves died, and measuring how far they were from

the high-tide line, Duke hopes to figure out how much of the die-off

is attributable to hot water and air, and how much to the dry

weather. But, for now, Duke thinks all are to blame. “This is all

correlated, so it’s hard to separate,” Duke says.

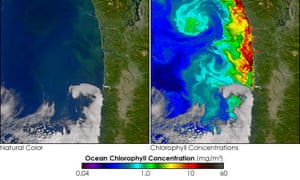

NASA’s image of the algal bloom. Photograph:

NASA images/SeaWiFS Project, NASA/Goddard Space Flight Centre and

ORBIMAGE.

Greg Browning from the Australian Bureau of

Meteorology says with all these changes in the water temperature and

the rainfall, big changes in ecosystems would almost be expected. “In

a nutshell, there have been significantly below-average rainfall

totals in the last two wet seasons ... and very warm sea surface

temperatures,” he told

the Guardian in July. “When you have those departures from

average conditions, it’s bound to affect the ecosystem in some

way.”

Just like the kelp forests and the coral reef,

there is a distinct possibility some of these mangroves will be lost

forever. Duke says if the disruption is severe enough, the

mangrove-dominated regions can become salt pans – flat, unvegetated

regions covered in salt.

And he says the most recent satellite images show

the mangroves still haven’t recovered their leaves, suggesting they

really are dead.

And last, but not least, Tasmania has been

virtually poached this year.

Tasmania was bathed in an unprecedented

pool of warm water that was 4.5C higher than average, devastating

lucrative oyster farms, causing a drop

in salmon catches and killing swathes of abalone.

Are marine heatwaves on the rise?

With two of the world’s global warming hot spots

sitting just off the coasts of Australia, the country is likely to

continue seeing these marine heatwaves bring chaos and destruction.

But the big question facing researchers is if they

are increasing in frequency or severity or both, as a result of

global warming.

Wernberg says it’s the apparent increase in the

effects of marine heatwaves that has driven him and others to study

them in more detail than ever before.

“It’s not that they’ve been understudied in

the past,” he says. “It’s that they didn’t occur to the

extent they are now.

“It seems like there are more and more extreme

impacts attributed to them.”

Wernberg says it’s difficult to say “because

you have one, then you have another one and then eventually you

realise you are having more than you used to”.

Di Lorenzo, an oceanographer at Georgia Institute

of Technology in the US, conducted a major

study of “the blob”, which, at least by some measures, was

the worst marine heatwave ever seen.

He says his study suggested it was made about 16%

more likely as a result of climate change – but he warns that while

he’s confident that the results show it was made significantly more

likely by climate change, he’s not very confident with the precise

figure. “I would feel comfortable with the sign of the effect, not

necessarily with number.”

But generally, Di Lorenzo says, looking at what is

happening, he thinks climate change is increasing both the frequency

and severity of marine heatwaves. So much so, he wonders if climate

models are wrong, and underestimating the fluctuations in temperature

that will occur as the globe warms.

“The real system – if you look at the

observations, and this is a paper I will publish very soon – the

increase in variance is much much stronger than what models are

predicting,” he says. “Maybe our models are too conservative.”

Di Lorenzo says this sort of “variance” –

including things like heatwaves – will always be stronger in the

ocean, because the ocean has a kind of “memory” that means events

build on top of each other, multiplying their effects.

That memory is a result of temperature changing

much more slowly in the ocean, as well as the ocean being able to

absorb more heat in general.

Oliver, from the University of Tasmania, would not

discuss the results because they were under review at a journal but

data he

presented at a conference, he and colleagues including Wernberg,

found “more, longer, and more intense” marine heatwaves over the

past century.

The results have not yet undergone peer-review but

they found the same trend in many parts of the world. Since 1920,

they found some regions were seeing an increase in frequency of about

one extra marine heatwave every 20 years. But the plots show most of

that increase happened in the past 30 years.

They also found they’re becoming hotter,

increasing by almost 0.4C per decade in some regions. And they’re

lasting longer – an extra 0.4 days per decade.

Putting it all together, the results globally were

even more significant. Around the world, marine heatwaves were

increasing by two days every decade since 1900.

Over that time, he found the frequency and

duration had doubled. As a result, the number of days in which there

was a marine heatwave somewhere in the world had increased four-fold.

“On average, there are 20 more [marine heatwave]

days per year in the early 21st century than in the early 20th

century,” the presentation concluded.

Oliver and Wernberg declined to comment on the

results, since some scientific journals refuse to publish results if

the authors have already discussed them with the media.

But Di Lorenzo, who wasn’t involved in Oliver’s

study, said the increasing frequency of these events is well outside

of what anyone predicted, and he’s excited to see how it turns out.

“I personally, as a scientist, I’m curious to

see what happens. I hope to live long enough – maybe 20 or 30 years

– to see what this experiment is going to turn into.”

He said the situation is very grave for humanity

but exciting for scientists. He compared the situation to a surgeon

being faced with a sick patient. “If he has a very complicated

surgery, of course he cares for the patient, but on the other hand he

is very excited about trying a new surgery and potentially solving

it.”

No comments:

Post a Comment