Extract from The Guardian

A year since he toppled

Tony Abbott, the PM must negotiate land mines and contingencies

everywhere, plus enemies inside the party and out

After just one year in the job, an Australian

prime minister in normal circumstances would be entitled to feel that

there wasn’t a sense of semi-permanent contingency. No such luxury

for Malcolm Turnbull. Photograph: Ye Aung Thu/AFP/Getty Images

Contact

author

Friday

9 September 2016 16.52 AEST

Malcolm

Turnbull had a terrible opening to the new parliament.

Pretty much everything went south.

The

prime minister had a better week this week. He could enjoy being out

of the Canberra crucible in

full geopolitical flight, happy in summit mode, and he could

enjoy the spectre of Sam

Dastyari’s imbroglio, an opposition imbroglio, rather than an

imbroglio of his own – a moment of pure refreshment.

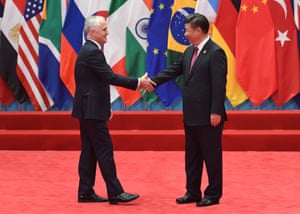

Malcolm

Turnbull shakes hands with China’s President Xi Jinping at the G20.

Photograph: Greg Baker/AFP/Getty Images

But

there’s no avoiding a return to the political fray.

Turnbull’s

plane will thud down on the tarmac at midnight on Saturday.

The

upcoming week marks not only the resumption of the parliamentary

sitting but the anniversary of Turnbull’s first year as prime

minister. Milestones inevitably prompt reflection and analysis, and

doubtless we’ll see a lot of it over the coming days.

After

just one year in the job, an Australian prime minister in normal

circumstances would be entitled to feel that the clock wasn’t

always ticking, that there wasn’t a sense of semi-permanent

contingency.

But Australian

politics hasn’t been normal for quite some time, and

sometimes it’s hard to see when or if it will ever be normal again.

Right

now, it is line ball whether the prime minister will survive in the

job long enough to see another election. His

enemies are massing in plain sight, not even bothering to be

covert in order to afford him a measure of dignity.

The Coalition remains

philosophically riven along the widest spectrum of representation

we’ve seen in the federal parliament in a generation, perpetuating

an internal dynamic of rolling contest and contention, and there are

no easy ways to paper over the divisions. The centre-right tribes are

fractured, which creates difficulties when attempting to seek an

organising principle, a campfire of common values.

Turnbull’s

personal objective over the last year was simple: wrest back the

leadership of the Liberal party from Tony Abbott, then try not to

repeat the mistakes of his last period of opposition leadership.

Rather than bend the Liberal

party to his will, this time he would try to build some

bridges.

The

concessions first up – bowing to the culture war preoccupations of

the party’s conservative wing: keeping

the marriage equality plebiscite, the hat-tipping to George

Christensen on the safe schools program, a

wink and a nod on reforming the Racial Discrimination Act,

keeping climate change on the absolute down-low. These were all an

effort to maintain internal equilibrium for long enough to get to an

election more or less in one piece, then seek a personal mandate,

which might allow a for a better balance between the Malcolm of old

the voters recognised – let’s call him Q&A Malcolm – and

the new prime ministerial construct he’d become.

The

second phase of leadership, after the emblematic genuflections to the

internal enemies, was supposed to be about resetting the economic

narrative. That was, after all, the

reason given for the brutal and meticulously planned

execution of Abbott. As well as driving the country mad with his

frolics and antiquated

crusades, Abbott had failed the fundamental test of economic

leadership.

Facing

reporters on 14 September, Turnbull declared: “It is clear enough

that the government is not successful in providing the economic

leadership that we need. It is not the fault of individual ministers.

Ultimately, the prime minister has not been capable of providing the

economic leadership our nation needs. He has not been capable of

providing the economic confidence that business needs.” There

were petty power struggles obvious enough to spill over into the

public domain

Everyone

could at least agree on that.

With

the emphatic sweep of Team Turnbull back into power in the capital,

confidence was to be king. We moved into the Exciting Times, and the

relief around the country was palpable. It was as if a dark cloud,

slung low across the landscape, misting out the sun, had suddenly

lifted. Business could barely contain its rejoicing, the polls

soared, the country was permitted to think beyond the cartoonish

black and white propositions of the Abbott era. A quick package on

science and innovation, a couple of passions. Then a swerve into the

tax reform debate, which was supposed to be about reinforcing

Turnbull’s intrinsic strengths as some kind of futurist guru, a

seer with the mental acuity and entrepreneurial capacity to know how

to recalibrate Australia’s economy from a mining boom to something

else.

Malcolm

Turnbull announces his new cabinet at a press conference with Julie

Bishop on 20 September 2015. Photograph: Peter Parks/AFP/Getty Images

But

the tax debate quickly fell into chaos. Turnbull’s tendency to want

100 flowers blooming simultaneously, his venture capitalist instincts

to extend mightily, contract sharply when reaching the limits of a

concept and recalibrate instantly into the next thought, looked more

unsteady than bold. The brash and the rash collided inelegantly into

the punishing demands for simple answers generated by a news cycle

that throbs in the thrall of the new, lives to punish, and never

sleeps.

It

also became clear that Turnbull and his treasurer, Scott

Morrison, were not really on the same page. There were petty

power struggles obvious enough to spill over into the public domain.

Then competitive federalism enjoyed a short boom, bust cycle. The

states would levy their own income taxes. Actually they wouldn’t,

because they didn’t want to.

The

gloss was coming off, and the stampede to an early election was

gathering pace. Magic bullets started to look enticing – a Senate

reform debate, presaging a run to a double dissolution election, that

would deliver that magic mandate where everything could become a

little easier.

The

mandate was supposed to be emphatic. It was an illuminated landmark

on the horizon, encouraging steady marathon swimming in choppy

waters.

But

of course the mandate didn’t materialise. After an eight week

campaign that comprehensively failed to detect and speak to the

national mood, Turnbull is back in power by a whisker. His fury at

the apparent indifference of fate to what is supposed to be the

inexorable rise of Malcolm rang out just after midnight on election

night on 2 July: shock, anger, disbelief, utterly unvarnished; the

director’s cut. Once seen, never forgotten.’

Malcolm

Turnbull addresses party members during the Liberal party election

night event at the Sofitel Wentworth hotel in Sydney. Photograph:

Lukas Coch/AAP

The

complexity of governing in the contemporary era swallows prime

ministers whole. Being freed of responsibility confers a kind of

lightness. While Turnbull has been executing his complex gambit, Tony

Abbott has been running his own.

Labor’s

last term in office tells us all we need to know about the dangers of

former prime ministers remaining on in public life, thwarted

political ambition metastasising into some hydra-headed monster. We

know how the story can go, the recent experience remains visceral.

Abbott

spent a period lying low after his public execution, watching the

Turnbull ascendancy soaring overhead, watching on unhappily as

colleagues trashed his period in government as an abject disaster,

which, of course, it was. The conservative wing, apart from the loyal

old factional generals, Eric Abetz and Kevin Andrews, switched over

into post-Tony mode, moving on to next generation options, cutting

their losses with a person who had failed their common cause.

But

Abbott is a politician of vaulting ambition. As a person, he’s

driven and hyper-competitive. He pushes himself to physical

extremity. The events of last September proved to be not an end, but

the opening of a new phase.

Abbott’s

first cycle of rapprochement with colleagues has been contrition. The

second has been public forays that are designed to have demonstration

effects: they are designed to show that he can lob simple rhetorical

bombs that resonate with the base, and pierce the default distraction

of ordinary voters going about their lives. Colleagues are invited by

inference to compare and contrast the style with the current occupant

of the Lodge.

Word

around the Coalition is Abbott is writing a book about how to be a

conservative political party, a new manifesto post Battlelines. The

internal feedback in the Coalition suggests Abbott is currently

feeling out the landscape, working out where various people are,

building bridges, trying to cultivate networks.

But

Abbott is not the only person positioning out of a calculation that

the Turnbull experiment won’t last.

Turnbull’s

relationship with his deputy, Julie

Bishop, suffered a blow post-election when he very obviously hung

her out to dry during the cabinet deliberation about whether or not

to anoint Kevin Rudd as Australia’s candidate to lead the United

Nations. Bishop is an incredibly hard worker who is assiduous with

the backbench, doing what needs doing, being where they need her to

be, and in politics, that counts for a lot.

Peter

Dutton is the most important conservative figure in the

parliament. Scott Morrison’s ambition is ever present on Ray

Hadley’s morning program on 2GB, more present, in fact, than the

consistency of his performance as treasurer.

In

the next generation Josh

Frydenberg is a man on the move if we’ve ever seen one, an

relentless networker, a builder of bridges between the moderate wing

and the conservative wing. It was notable Turnbull gave Frydenberg

climate change when he refashioned his ministry post election,

something of a poisoned chalice. A meaty conundrum to occupy a fellow

of momentum.

Christian

Porter also has a lot of fans internally because of his grasp of

complex and complicated policy issues. Of the generation beyond,

Angus Taylor is one of those parliamentarians who succeeds in putting

himself on a travelator, understanding the art of the calculated

intervention on issues that colleagues care about.

This

catalogue of ambition is not meant as one of those dispiriting race

call assessments that now pour out of Canberra in substitution for

investigations or deep policy analysis, it is not meant to be another

manifestation of our apparently endless appetite for instability –

in truth, I’m exhausted by it. The whole system feels diminished

and frayed and rudderless.

Politicians

live to plot, but the political class is also exhausted by the

relentless zero sum of the past few election cycles. That exhaustion

factor is one component that makes Turnbull’s future hard to

predict.

"Turnbull

has been too preoccupied righting the wrongs of 2009 to understand

that he’s now in a wholly different phase"

But a

few things are clear one year down the track.

There

were always people inside the Liberal party who were going to resist

the Turnbull experiment, because they view him as an interloper, a

person in the wrong party, too centrist, too dismissive of

conservative shibboleths, too unbound by the conventions of the

institutional game of politics, a person without a power base, a

person too intent on a frolic of his own.

Those

people were never going to shift. They were never going to be

pacified by charm, or appeasement, by genuflection, or collaboration,

they would take it as weakness, and use the weakness to wear him down

before tearing him down. Turnbull’s appeasements to enemies have

disconcerted the public, damaging the source of his power, his

bankable currency for the Liberal party, which has been his strong

connection with the public.

Turnbull

has been too preoccupied righting the wrongs of 2009 to understand

that he’s now in a wholly different phase of operation, and time

has already wrenched him past the zenith of his authority.

Currently

he seems preoccupied with having an ideal prime ministership, the

prime ministership you would have in the best of times, except

there’s a persistent, gnawing vacuum. What is he about? What is

this period in government about? What’s the agenda, what will he

live to achieve, or die trying? Can the Liberal party agree on

anything sufficiently to face the voters with anything approximating

a compelling reason to govern?

How

does the government grapple with the big questions of the age – the

rise of protectionism, the post global financial crisis lapse

into xenophobia, the question of how the centre right develops an

active agenda to better distribute the benefits of globalisation in

order to maintain the fracturing public consensus around the open

markets model, how will we face up to the

shameful way we treat asylum seekers in offshore detention, how

will we fix that sub-optimal

climate policy that either won’t see us meet our

international obligations, or do it at a cost the budget can’t

afford, how will political consensus be reached around fiscal repair

in this term so we can safeguard the country in the event of another

economic shock?

Turnbull

has been acting like a prime minister with time on his hands – time

to recover from an election setback, time to plug in to the great

geopolitical developments of our age, time to play a part, time to

determine a new agenda for a new parliament, time to do some good on

a range of fronts, time to fight on and live another day, another

week, another month, another term.

Perhaps

he’s acutely aware of the difficulties he’s in, yet he’s seemed

slow to grasp the harsh political realities of his post election

position – land mines everywhere, contingency everywhere.

Here

is the brutal reality facing Malcolm Turnbull as he faces his first

anniversary in the job he’d always wanted.

He

doesn’t have time.

He

has now, and he wastes now at his peril

No comments:

Post a Comment