The

pallid blue light of my phone cut through the gloom of my bedroom. I

turned over, reached for it and read an email that had just come in.

Before putting my phone down again, I looked at the time. 2.03am. “What

am I doing?” I asked myself as I drifted back to sleep.

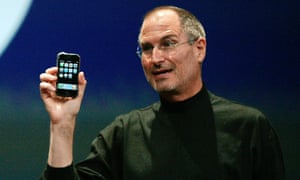

When I woke up four hours later, I reached for my phone – and, out of habit, I began to scroll through social media. One of the first news stories I noticed was that the Apple iPhone has turned 10 years old. I wondered how much our life had changed in that period thanks to this iconic piece of technology. After a quick Google search, I discovered that four in five adults in the UK now have a smartphone, and that the average US citizen looks at their device 46 times a day; if they are 18-24 years old, they look at them 74 times a day. We use our smartphones when walking down the street, watching films, or while in places of religious worship. One in three adults admits to checking their phone in the middle of the night; 12% admit to using their phone while taking a shower; and 9% say they check their smartphone during sex.

Putting down my phone, I started to get ready for the day ahead. As I showered I remembered a strange meeting I had attended a few months earlier. I was in a windowless room filled with top European banking executives. Before the meeting began, the bankers were each handed an envelope and told to put their phone inside. Each dutifully followed orders, sealing up their device and writing their name on the envelope. But within five minutes, I could see these seasoned bankers staring longingly at the package with their name on it.

After 10 minutes, many were physically agitated, drumming their fingers on the table or scribbling manically on the paper in front of them. After 30 minutes, the chairman of the board could no longer stand it – and he ripped open his envelope and began sending messages. When the coffee break finally came, all the others in the audience lunged towards their own envelopes and sighed with relief as they began to scroll through their emails. It was like watching crack addicts getting their first hit of the day.

After getting dressed, I headed out of the door. On the bus, I couldn’t get the memory of these smartphone-obsessed bankers off my mind. I opened up my phone again and discovered that there is an established affliction called “smartphone addiction”. There was even a scientifically validated test I could do to work out how addicted to my smartphone I was. As I read on, I found out that a national research agency in South Korea estimated that 8.4% of young people in that country exhibited smartphone addiction. I suspected the rates could be just as high in Europe and the US.

As the bus filled up, I read about how smartphones often trigger a dump of dopamine – the same hormone which is usually triggered by sex, food, drugs and gambling. I discovered that when addicts were separated from their phones, they would experience mounting anxiety, increase in blood pressure and heart rate – and even phantom sensations of mobile phone vibrations.

I knew that smartphone use was associated with sleeping problems. What I didn’t know was that heavy smartphone users were more likely to have high levels of anxiety and depression.

Getting off the bus, I started wondering why we were so addicted to our devices. As I walked towards my office, I continued my search. It seemed that in the past few years, psychologists have come up with some explanations. The most well-known is the fear of missing out, or Fomo. We keep looking at our phones to be sure we don’t miss out on something which is happening – whether that is an important message or just a piece of incoming news.

As I waited for the lift, I came across two other explanations for our dependency. One was that people just love to touch their phones. Indeed, psychologists have found that people who have very high need for human contact were likely to be even more addicted to their phones. Those with high levels of social anxiety were also more likely to develop a dependency. The socially anxious are people who worry about social interactions and tend to avoid them if possible – and smartphones give them the ideal way of avoiding an encounter they could find disturbing.

Opening my office door, I started to wonder which one of these reasons was behind my own tendencies towards smartphone addiction, which I had been struggling with since I bought my first iPhone 10 years ago. Has this magical little device done more harm than good?

When I woke up four hours later, I reached for my phone – and, out of habit, I began to scroll through social media. One of the first news stories I noticed was that the Apple iPhone has turned 10 years old. I wondered how much our life had changed in that period thanks to this iconic piece of technology. After a quick Google search, I discovered that four in five adults in the UK now have a smartphone, and that the average US citizen looks at their device 46 times a day; if they are 18-24 years old, they look at them 74 times a day. We use our smartphones when walking down the street, watching films, or while in places of religious worship. One in three adults admits to checking their phone in the middle of the night; 12% admit to using their phone while taking a shower; and 9% say they check their smartphone during sex.

Putting down my phone, I started to get ready for the day ahead. As I showered I remembered a strange meeting I had attended a few months earlier. I was in a windowless room filled with top European banking executives. Before the meeting began, the bankers were each handed an envelope and told to put their phone inside. Each dutifully followed orders, sealing up their device and writing their name on the envelope. But within five minutes, I could see these seasoned bankers staring longingly at the package with their name on it.

After 10 minutes, many were physically agitated, drumming their fingers on the table or scribbling manically on the paper in front of them. After 30 minutes, the chairman of the board could no longer stand it – and he ripped open his envelope and began sending messages. When the coffee break finally came, all the others in the audience lunged towards their own envelopes and sighed with relief as they began to scroll through their emails. It was like watching crack addicts getting their first hit of the day.

After getting dressed, I headed out of the door. On the bus, I couldn’t get the memory of these smartphone-obsessed bankers off my mind. I opened up my phone again and discovered that there is an established affliction called “smartphone addiction”. There was even a scientifically validated test I could do to work out how addicted to my smartphone I was. As I read on, I found out that a national research agency in South Korea estimated that 8.4% of young people in that country exhibited smartphone addiction. I suspected the rates could be just as high in Europe and the US.

As the bus filled up, I read about how smartphones often trigger a dump of dopamine – the same hormone which is usually triggered by sex, food, drugs and gambling. I discovered that when addicts were separated from their phones, they would experience mounting anxiety, increase in blood pressure and heart rate – and even phantom sensations of mobile phone vibrations.

I knew that smartphone use was associated with sleeping problems. What I didn’t know was that heavy smartphone users were more likely to have high levels of anxiety and depression.

Getting off the bus, I started wondering why we were so addicted to our devices. As I walked towards my office, I continued my search. It seemed that in the past few years, psychologists have come up with some explanations. The most well-known is the fear of missing out, or Fomo. We keep looking at our phones to be sure we don’t miss out on something which is happening – whether that is an important message or just a piece of incoming news.

As I waited for the lift, I came across two other explanations for our dependency. One was that people just love to touch their phones. Indeed, psychologists have found that people who have very high need for human contact were likely to be even more addicted to their phones. Those with high levels of social anxiety were also more likely to develop a dependency. The socially anxious are people who worry about social interactions and tend to avoid them if possible – and smartphones give them the ideal way of avoiding an encounter they could find disturbing.

Opening my office door, I started to wonder which one of these reasons was behind my own tendencies towards smartphone addiction, which I had been struggling with since I bought my first iPhone 10 years ago. Has this magical little device done more harm than good?

No comments:

Post a Comment