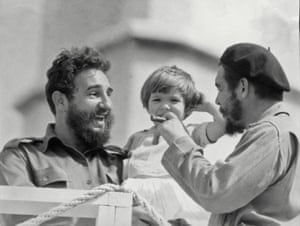

On the right is my father, cigar in hand, talking to his lifelong friend Fidel Castro,

a fellow communist revolutionary. The angle makes it look like my

father is holding out his cigar to me, but that’s not the case. It was

unusual that he’d smoke around me. I don’t remember this picture being

taken, or by whom; I was too young. I’d have been around three at the

time. I was born in November 1960, and I’ve since been told it was 1964

in Plaza de la Revolución in Havana.

I’m the eldest of Che’s four children with my mother. Papi was known around the world as the Argentine revolutionary, a guerrilla leader and major figure of the Cuban revolution, but we were just a normal family. I never felt special as his daughter. Where I did feel special was as the child of a couple who loved each other dearly.

As children, we enjoyed Papi very little. I was only six when he was executed in Bolivia 50 years ago, on 9 October, 1967. Our mother formed our values and kept him alive in our memory long after he died. She never used him as a way to tell us off or threaten us. Papi was always the good guy.

We never enjoyed any privileges: my father was opposed to that, and my mother maintained the line. When she became a widow with four small children, my father’s friends wanted to help. They couldn’t replace the affection that had been lost, so tried to give us material things. My mother wouldn’t permit anything at all. She told us, “You must have your feet firmly on the ground, and let pass everything you haven’t earned yourselves.” That was an important lesson.

We went through difficult periods. In my teenage years, she’d make trousers for my brothers with material from her old blouses. But we were happy: we’d play, we’d laugh. We grew up like Cuban children, alongside the people in our community.

I was close to Fidel and comfortable with him. I have very fond memories – I would call him “mi tío”, which means “my uncle”. I maintained a relationship with him right up until the end of his life last year. He’s holding me and I’m relaxed, smiling. My father and Fidel were always happy and joking together; there was much mutual respect and confidence there.

Fidel wanted to break the news to us children when Papi died, but my mother insisted it was her duty. But he told us that Papi had written a letter saying that if one day he fell in combat, we were not to cry for him: when a man dies trying to achieve what he wants to achieve, one doesn’t need to. The next day, I was called in to see my mother, who was in tears. She sat me on the bed and pulled out the farewell letter from Papi.

“When you see this letter,” it said, “you will know that I am no longer with you.” I started crying, too. The letter was very short. It ended with the words: “Here is a big kiss from Dad.” I understood I no longer had a father.

I still live and work in Havana, as a paediatrician, and feel hopeful for the future of Cuba. Do I have hope for humanity? None of us has a crystal ball, but if we want a different world, we need to work to achieve it. We can’t wait for it to fall out of the sky. We have a duty to forge that future ourselves.

I’m the eldest of Che’s four children with my mother. Papi was known around the world as the Argentine revolutionary, a guerrilla leader and major figure of the Cuban revolution, but we were just a normal family. I never felt special as his daughter. Where I did feel special was as the child of a couple who loved each other dearly.

As children, we enjoyed Papi very little. I was only six when he was executed in Bolivia 50 years ago, on 9 October, 1967. Our mother formed our values and kept him alive in our memory long after he died. She never used him as a way to tell us off or threaten us. Papi was always the good guy.

We never enjoyed any privileges: my father was opposed to that, and my mother maintained the line. When she became a widow with four small children, my father’s friends wanted to help. They couldn’t replace the affection that had been lost, so tried to give us material things. My mother wouldn’t permit anything at all. She told us, “You must have your feet firmly on the ground, and let pass everything you haven’t earned yourselves.” That was an important lesson.

We went through difficult periods. In my teenage years, she’d make trousers for my brothers with material from her old blouses. But we were happy: we’d play, we’d laugh. We grew up like Cuban children, alongside the people in our community.

I was close to Fidel and comfortable with him. I have very fond memories – I would call him “mi tío”, which means “my uncle”. I maintained a relationship with him right up until the end of his life last year. He’s holding me and I’m relaxed, smiling. My father and Fidel were always happy and joking together; there was much mutual respect and confidence there.

Fidel wanted to break the news to us children when Papi died, but my mother insisted it was her duty. But he told us that Papi had written a letter saying that if one day he fell in combat, we were not to cry for him: when a man dies trying to achieve what he wants to achieve, one doesn’t need to. The next day, I was called in to see my mother, who was in tears. She sat me on the bed and pulled out the farewell letter from Papi.

“When you see this letter,” it said, “you will know that I am no longer with you.” I started crying, too. The letter was very short. It ended with the words: “Here is a big kiss from Dad.” I understood I no longer had a father.

I still live and work in Havana, as a paediatrician, and feel hopeful for the future of Cuba. Do I have hope for humanity? None of us has a crystal ball, but if we want a different world, we need to work to achieve it. We can’t wait for it to fall out of the sky. We have a duty to forge that future ourselves.

No comments:

Post a Comment