Extract from The Guardian

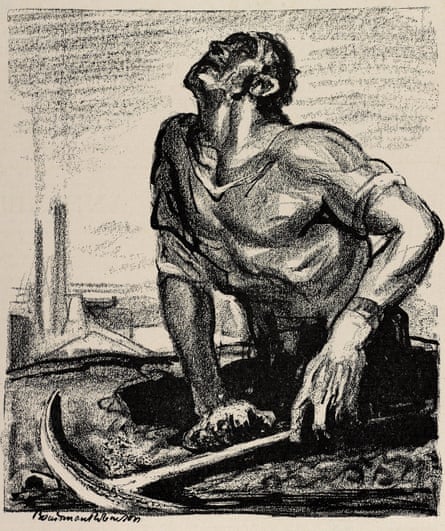

Altura Lithium Project at Pilgangoora in WA’s Pilbara region. Photograph: Altura

“Where are you going to find experienced lithium miners? That’s like finding unicorns,” laughs James Brown, the managing director of Western Australian resources firm Altura Mining.

Brown is the next best thing. Hailing from a family five generations deep in coal mining, the burly Queenslander never imagined he’d be applying his expertise to digging out a key building block of a low-carbon economy.

For a man not particularly fussed about the climate crisis, it’s an unlikely sector to have ended up in. But when it comes to lithium, the two factions of Australia’s climate wars have reached an uneasy truce.

On the one side, environmentalists are engaging with a resources sector they distrust to nudge it towards lithium, an element which is used in batteries for electric vehicles and renewable energy storage systems due to its remarkably high energy density.

On the other, miners like Brown are suppressing scepticism of green causes to carve out a future in a world aiming to divest itself of fossil fuels.

Brown joined Altura Mining in 2009, and set about helping the small coal miner diversify into other resources as a way of hedging against headwinds facing the fossil fuel.

Lithium, hyped as the “white gold” of the 21st century, seemed a promising investment. But securing investors for Altura’s exploration tenements in the remote ochre deserts of the Pilbara proved challenging.

“What I didn’t

realise was how difficult it would be to fund the project while

remaining a coal miner,” Brown says. “Our fund manager said: ‘you guys

owning both coal mines and lithium is like a health fund owning a

tobacco company.’”

And so lithium evolved from Altura Mining’s backup, to its main plan. Brown concedes the company still owns undeveloped coal assets, but he claims it is only because they’ve proved difficult to sell.

Despite the urgency of the climate crisis, the attachment to coal runs deep for Australians like Brown, and leaving it behind wasn’t easy.

His family connection to the fossil fuel stretches back at least to his great grandfather, who left the UK for Australia in the early 1900s during the turbulence of the coal strikes, when miners were fighting for the right to a minimum wage.

The family moved to Ipswich, Queensland, where Brown’s grandfather was sent to work in the mines from the age of 13.

The tradition continued with his father, who laboured for 40 years with local coal operator New Hope Group.

Brown’s childhood memories are of miners’ picnics, playing for the Coalstars soccer team, and dreams of joining his father in the mines when he was old enough. The union made sure family members got a look in.

When the time came, however, he was soundly rejected. Brown was left handed, but the equipment was designed for right handers. “As soon as they saw my watch on my right hand, nobody wanted me as an apprentice,” he says.

Brown was still able to work in the sector as a cartographer, and then as a civil engineer at New Hope. Brown’s son also went on to become a mining engineer.

All that experience has held Brown in good stead, with Altura Mining one of the few to transform Australia’s much-hyped lithium potential into commercial reality, in a sector littered with failed ventures.

The ‘white gold’ rush

Australia leads the world in lithium production and possesses an estimated 6.3m tons of lithium reserves.

The metal is fast becoming a geopolitical bargaining chip, as China, the US and other major powers jostle to secure access to an element expected to surge in demand as the global economy rapidly ramps up production of electric vehicles and renewable energy storage systems, not to mention lithium-ion mobile phone batteries.

Lithium is

abundant and even found in seawater, but at such low densities that

commercial extraction is not yet feasible. As such, a handful of

countries with extractable reserves in hard rock – like Australia – and

in the brine of salt lakes are growing in geopolitical importance.

Harry Fisher, senior consultant at business intelligence company CRU Group, believes the economic recovery from Covid-19 will be the moment the long-promised lithium rush finally gets underway.

“Governments continue to promote the merits of a ‘green recovery’, with EV subsidies being increased in Germany, France, UK and many others,” he says. “Policy is likely to continue to support demand.”

Australia has no formal green recovery plan, but Fisher suggests that might not matter if the rest of the world does.

Fisher forecasts that demand will grow to 830 kilotonnes by 2025, up from around 330 kilotonnes this year. In particular demand, Fisher says, is the spodumene that Australia specialises in.

A smaller footprint

The Covid-19 shutdown has presented challenges, and with lithium yet to hit the heights projected, the sector is doing it tough. Altura Mining is currently restructuring its debt arrangements and has suspended shares from trading as it navigates the crisis.

Despite the challenges, the company shipped a record 60,950 wet metric tonnes of spodumene concentrate for the June 2020 quarter. The lithium is mined at the company’s flagship Altura Lithium Project at Pilgangoora.

Brown in June signed a five-year offtake agreement with a subsidiary of Ningbo Shanshan, one of the world’s major suppliers of battery components for electric vehicles and green energy storage.

Altura will be a key supplier to Shanshan’s new lithium chemical plant in China, which plans to produce 25,000 tonnes per annum.

The deal came, says Brown, thanks to China’s two-year extension of state subsidies and tax breaks for electric vehicles until the end of 2022.

The subsidies were also cited by Pilbara Minerals, the operator of a neighbouring Pilgangoora lithium mine, as a reason for optimism.

Australia’s

major competition in the global market is the “lithium triangle” of

Bolivia, Chile and Argentina, which extracts the metal out of the

region’s salt lakes.

This form of lithium mining has attracted criticism for drawing on water supplies in the region, encouraging companies such as BMW to point to use of Australian hard rock lithium in their electric vehicles to burnish their sustainability credentials.

Elsa Dominish, research principal at the Institute for Sustainable Futures, said the environmental impact of lithium mining is similar to other forms of hard rock mining.

She says Australia has an opportunity to establish the world’s best practice for lithium mining by monitoring water and energy use, management of waste, and impact on sacred cultural sites.

Dominish emphasises that lithium’s footprint pales in comparison to the impact of coal. “In addition to emissions … coal mining is one of the most damaging forms of mining considering health and environmental impacts, particularly respiratory impacts from exposure to coal dust,” she says.

Coal miners v inner-city progressives

Lithium doesn’t just offer a practical solution to carbon emissions; it also represents a political solution.

The Australian Labor party has twisted itself into knots trying to appeal to both working class coal miner workers and progressive inner-city voters concerned about climate change.

The party is looking to make the case for a just transition for miners into work with emerging metals like lithium.

The Greens have similar ideas. When Adam Bandt assumed the Greens leadership in February, he immediately went to work spruiking a Green New Deal.

Bandt had even planned to visit the Greenbushes Lithium Mine in south-west WA, the largest hard rock lithium operation in the world, to sell the message of transitioning coal miners into jobs in new energy metals. The trip was called off due to the Covid-19 crisis.

Miners have long moved to where the resources are, and Queensland and New South Wales coal workers might need to relocate to the Pilbara for new lithium mining gigs. In the case of Greenbushes however, there is a coal mining community right on its doorstep.

Unions and the Western Australian government are pushing for a planned Greenbushes expansion to employ coal workers from the nearby Collie mine and power plant, in a bid to secure a future for them as the local coal industry withers away.

Industry analysts, lithium miners, and green groups also agree on something else: simply digging the lithium out of the ground and exporting it with minimal processing is a wasted opportunity.

According to the Million Jobs Plan report, produced by climate thinktank Beyond Zero Emissions, Australia earns only 0.5% of the value of its exported lithium ore, with the remainder going to overseas companies that further refine it and manufacture lithium-ion batteries.

South Australia, home to Tesla’s Big Battery, is developing battery manufacturing capacity, and BZE argues Western Australia could invest in lithium refinement, battery component manufacture, and recycling, to contribute towards 100,000 new jobs nationally by 2025. The state is already host to several processing facility projects.

Heidi Lee, project lead for the Million Jobs Plan, says the Covid-19 shutdown is a generational opportunity for the Australian government to set signals to unlock investment, such as a new renewable energy target.

“This is the moment we’re all sitting back, having to rethink what good looks like,” she says. “It’s not lithium for the sake of lithium mining, or processing for the sake of processing. It’s how these pieces all come together. So many parts need to move simultaneously to make this happen … the world has to move to all-electric [vehicles] to mitigate climate change, and that needs to happen quickly at scale.”

In response to questions about how the federal government is supporting the sector, a spokesperson for the Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources pointed to examples of general government support for resources that the lithium sector is eligible for, and the establishment of the Critical Minerals Facilitation Office and the Critical Minerals Portal.

Investments include $20m in Cooperative Research Centre Projects funding towards critical minerals, and a $25m spend on the Future Battery Industries Cooperative Research Centre, which seeks to “optimise value creation in downstream mineral processing, battery manufacture, deployment, reuse and recycling”.

Back at Altura Mining, Brown warns there are challenges in building up more of the lithium supply chain in Australia due to high energy and labor costs.

He’d like to see the federal government help the sector access low-cost capital.

“Australia has a habit of being just the raw material supplier, but if that’s the case we have to accept we’re buying the products back at a higher price,” he says.

Brown might not be buzzing about his role in addressing the climate crisis, but he is excited about what lithium represents – in his own way.

“Few people get the opportunity to be involved in new commodities,” he says, proudly. “That’s what we’re doing: we’ve gone from a rock chip sample to a mine. And it’s great to see that come to fruition.”

The coronavirus pandemic has devastated the economy but also presented a unique opportunity: to invest in climate action that creates jobs and stimulates investment, before it’s too late. The Green Recovery features talk to people on the frontline of Australia’s potential green recovery.

No comments:

Post a Comment