Extract from The Guardian

But instead, I sat on the bottom step and cried.

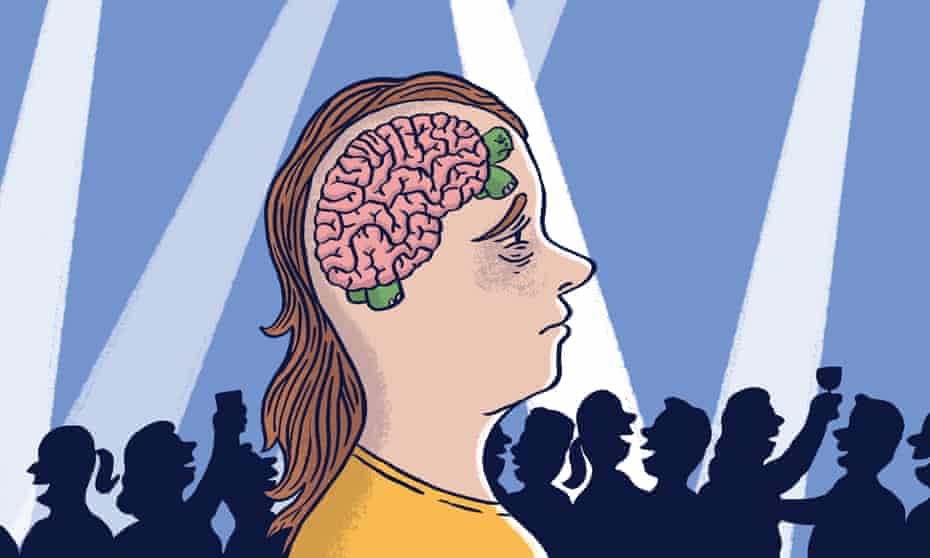

These past two years have pushed us to our limits and, at times, beyond. We have lived in an environment of constant and invisible threat. That sense of threat triggers the limbic system. The limbic system is awesome: it conveys information to us without it having to take the long route through the more sophisticated parts of our brain. That means that we can react to things in an instant – that old gut feeling.

When we are under stress, we rely on this part of our brain far more. That is great for dodging out of the way of oncoming buses, but less great when we are trying to do complicated things such as remembering that the kettle does not go in the fridge, good grief!

‘When you live through what we have lived through, the net result means being broken by tiny catastrophes.’ Photograph: Dominic Lipinski/PA

Our prefrontal cortex, that sophisticated part, is losing out in the great brain battle. It shows less activity when we are under stress. And so we become more error-prone, find rational thinking harder, decisions too complicated to process. And so, when the limbic system is in charge, what is left is emotion.

And a woman, sitting on the bottom step, crying over a lost shoe.

We think that we should be better at this stuff by now. And yet, for so many of us, our brains remain on high alert. Our limbic system still runs the show. That’s OK. It’s literally what it was designed for.

But what it means is that we might react more emotionally than we did before. That we will remember less, lose our tempers more. We try to talk ourselves down from whatever step we find ourselves sitting on today.

A proved technique for countering this is called reappraisal and it works by getting the prefrontal cortex to talk to the limbic system – in essence telling it to calm the hell down. Trouble is, the prefrontal cortex struggles to do that when we are tired or sick or… yes, you guessed it, stressed.

What psychological research tells us is that this – this phase we are in now, where everyone feels kind of on the edge but no one can really articulate why – is what happens when you survive a disaster. When you live through what we have lived through, the net result means being broken by tiny catastrophes.

It will pass. The research tells us that too. The brain is immensely adaptive and will figure out a way through this phase. In disaster survivors, PTSD is seen in a small proportion. For the vast majority, they will return to functioning as they did before. For another proportion, they will experience what is known as post-traumatic growth, a positive often overlooked. This breaking will make them stronger. (For instance, in studies of first responders, post-traumatic growth following a distressing incident showed prevalence rates of between 40-75%.)

It’s still early in our analysis of the effects of the pandemic, but there’s no reason to question the argument in a paper by Emma PeConga and others that “long-term resilience will be the most common outcome”. For the moment, I can’t make it better. I can’t take away what you have endured and what you still endure. What I can tell you is this – it’s OK. It is OK to sit on the step and cry over a lost shoe. It is OK to feel intense fatigue after a short period of concentration or to feel that you simply can’t concentrate at all. It is OK to feel broken.

Emotions feed off attention. When we scold ourselves for feeling them, we add to that attention

Psychological research has shown that when we do this, when we accept our emotions rather than trying to rail against them, it has a couple of effects. It reduces that secondary stressor – being stressed about being stressed. Emotions feed off attention. When we scold ourselves for feeling them, we add to that attention. We are then more likely to ruminate and feel increasingly negative.

Our memory works in what is known as a state-dependent way, which means that when you are feeling sad it is easier to remember other occasions on which you were sad. And round and round we go.

Naming the emotion, in a non-judgmental way, can help. When we name how we are feeling, we drag that prefrontal cortex back online, allowing it the opportunity to quieten the limbic system. And remembering there are no bad emotions. Emotions are there as signposts, indicators to us that there is something within our environment we need to pay attention to. Recognising how we feel, allowing ourselves to feel that way, is important.

I cry over a lost shoe not because I have entirely lost the plot. Or not yet, at least. I cry over a lost shoe because it is one tiny catastrophe too many for my poor, tired brain. And when your brain is pandemic-tired, sometimes that is all you can do. Allow yourself to grieve those tiny catastrophes and remind yourself that you are not alone.

No comments:

Post a Comment