Extract from Eureka Street

- Tim Dunlop

- 15 November 2021

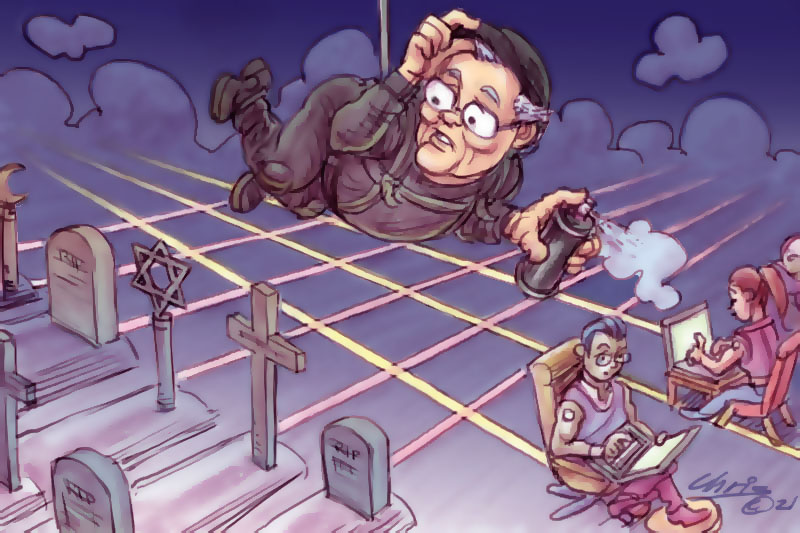

The experience of the Covid-19 pandemic has been like the aerosol used in those heist movies, where the cat burglar breaks into the museum and sprays the air to reveal the invisible lines of power that criss-cross the space between the door and cabinet where the treasure is kept.

The pandemic has exposed all the lines of power and inequality in our society and has set off alarms everywhere. A recent OECD webinar gives us a good idea of the range of that inequality, and participants discussed gender and spatial inequalities — everything from the global south versus the global north, to those who can work from home versus those who can’t — to issues around mental health and access to services, housing, and matters to do with education, employment generally, and migrant labour issues.

Covid’s exposure of these ley lines of inequality is, in other words, a global phenomenon. But I think it is has been particularly eye-opening for Australians, as we still flatter ourselves with the view that ours is a uniquely egalitarian society, one where the fair go, for the most part, still reigns.

As federal Labor MP Ed Husic noted in his recent Jack Ferguson Memorial Lecture, Covid showed us unequivocally that this isn't true:

At the start of the lockdown, some of the wealthiest suburbs in the city had vaccination rates three times higher than the west (and with a better ability to work from home). By the end of our lockdown, 60 percent of the deaths were experienced in the west and southwest of Sydney. Many of these deaths were preventable.

Melbourne suffered similar problems, with insecure workers in poorer areas forced to pursue risky work outside the home, often to allow those in richer areas to work from home in relative safety, while some groups, particularly those in public housing, were subject to more extreme forms of policing.

'The bonds of social coexistence are weakened as we allow those with means to opt out, to choose the nature and extent of their support for various policies, rather than just insist that they pay their tax like everyone else.'

The Covid-19 pandemic, then, has provided a wake-up call about the nature of inequality in our society, and what has become apparent, I think, is that we need to give some thought to our underlying values.

The point I want to make is that public policy and underlying values can’t be separated, and this has implications for how we approach inequality. Our values affect the policies we design, and the way we design policy influences how we are able to enact our values.

Neoliberalism rewired egalitarian Australia, coded a certain selfishness into our social operating system, and it has taken a society-wide disaster such as Covid to expose what has happened.

This rewiring is most obvious in regard to privatisation, a key plank of neoliberalism, where public ownership and service delivery has been replaced with for-profit corporations running everything from power and water supplies to the provision of retirement income in the form of superannuation, or the running of aged-care facilities.

At every level of society, privatisation enforces competition rather than cooperation, turning what were once services for the many into a means of making profit for the few. Even the chair of the ACCC, Rod Sims, has said that he no longer supports privatisation ‘because it’s been done to boost...asset sales, and I think it’s severely damaging our economy.’

The perniciousness of the neoliberal mindset is apparent when you hear Scott Morrison, then Minister for Social Services, tell an ACOSS conference that, ‘welfare must become a good deal for investors — for private investors.’

The idea that what governments used to do for all of us should now be the province of individual decisions and private profit even shows up around the issue of philanthropy, where the superrich get to arrange their wealth to maximally avoid tax, and then decide on their own terms to ‘give something back’.

In such ways, the bonds of social coexistence are weakened as we allow those with means to opt out, to choose the nature and extent of their support for various policies, rather than just insist that they pay their tax like everyone else.

Worst of all, in the words of academics Dick Bryan and Mike Rafferty, we have finacialised society, and in so doing, normalised the values that govern the competitive marketplace, turning them into social values.

In their book Risking Together, Bryan and Rafferty point out that the ‘underlying issues are... not so much to do with income inequality’ but with what they call the hidden inequality of ‘how financial volatility and risk ...impact differently on people of different incomes, wealth and life circumstances.’

Whether or not Australia was ever the classless nation of legend is a favourite debate in some intellectual circles, but it always missed the point. Any complex society is likely to stratify; what matters is how that stratification is managed, and I think a good case can be made that the way Australian governments, of any persuasion, handled that stratification, from Federation and into the 1980s, was fundamentally more egalitarian than Britain (our obvious point of comparison), and even than the United States, which remains in thrall to a form of hyper individualism that, until recently, never gained much traction here.

'Once market values are used to guide policy, they tend to override egalitarian intent, and we can see this with everything from the NDIS to unemployment benefits.'

Even our form of neoliberalism, instigated by the Labor Party, was ringfenced with various social policies — from Medicare to the pension — the so-called ‘third way’ of balancing market reform with a commitment to social welfare, and a key tool of that process was the move from universal benefits and entitlement to targeted welfare spending.

As political economist, Ben Spies-Butcher argues, ‘Australian reformers did not reject ...egalitarianism as an objective. Instead, reform sought to combine greater competition with compensation, generating larger inequalities in market incomes alongside growing social spending.’

And this is what I mean when I say neoliberalism coded selfishness into our social operating system: once market values are used to guide policy, they tend to override egalitarian intent, and we can see this with everything from the NDIS to unemployment benefits. Harsh conditionality and tight targeting undermine the social goals of such policies, turning the safety net into an obstacle course, a process that of itself tends to marginalise people rather than bring them in from those margins.

In a democratic society, government is meant to manage risk for all of us, to pool that risk and the resources necessary to deal with it — everything from national defence to public health to the challenges associated with old age — to even things out, so that no-one is left behind, no matter which LGA they live in.

Instead of managing risk through public policy, however, we are increasingly heightening it in private markets, and inevitably, and by design, creating winners and losers around the necessities of life.

As Bryan and Raferty note, ‘the growing vulnerabilities of ordinary people are systematic, not accidental’ and under such circumstances, risk ‘is framed in wider discussion as their personal problem, to be privately managed or endured.’ This is the flipside of the neoliberal deification of individuality and choice: increasingly, you are on your own.

Again, Covid has been the great revealer, and if we want to move to being the fair society of our (alleged) dreams, then matters of universality and non-conditionality around various welfare payments need to be on the table again. It will be interesting to see if the experience of the pandemic reignites Australia's egalitarian spirit.

No comments:

Post a Comment