Extract from The Guardian

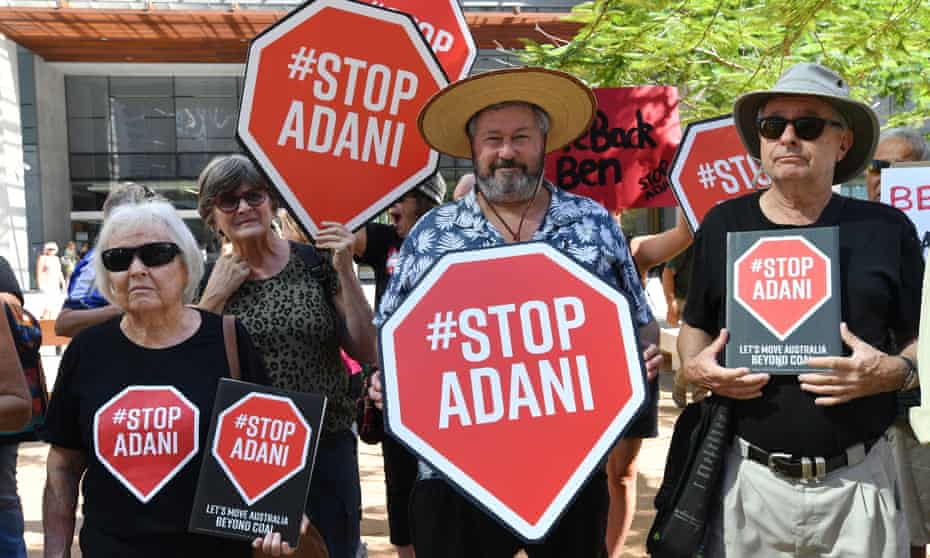

The controversial and politically divisive Carmichael mine has been locked in a battle with an uncompromising two-word slogan.

That purchase, by the conglomerate Adani Group, kickstarted one of the most controversial and politically divisive resource projects in Australia’s history – the Carmichael coalmine and rail project.

Before the year is out, and about eight years behind schedule, Adani says it will finally export its first coal, destined to be burned in a power station.

The moment will be celebrated as a victory by its supporters, including many regional Queensland MPs and senators and conservative commentators.

Australia’s resources minister, Keith Pitt, was at the mine site in October – about 300km west of Mackay – to record a video celebrating the first coal being dug. It would mean jobs and prosperity, he said.

Earlier this week, Adani Australia chief executive Lucas Dow told the ABC that coal had already been delivered to the company’s port at Abbot Point as the company runs tests of new trains along 200km of new railway lines. “We’re very excited as the project is nearing completion,” he said.

So as the first coal waits to wind its way through the Great Barrier Reef’s shipping channels, what now for that campaign?

“We would prefer to have stopped Adani when it went through approvals, or when it was looking for financing and then in construction. If we have to wait until the project is moving coal, then that’s what we’ll do,” says Julien Vincent, executive director of Market Forces, a campaign group that has worked to remove Adani’s opportunities to finance and insure the mine.

“There’s no asterisk or caveat or fine print. There’s no conditions. It’s just Stop Adani,” he says.

Carbon bomb

The Galilee basin has an estimated 23bn tonnes of coal.

When the first mine was proposed in 2012, Adani was one of about nine projects targeting the basin.

At the time, Greenpeace estimated if all the mines went ahead, the burning of the coal would release about 700m tonnes of CO2 into the atmosphere – almost one-and-a-half times Australia’s annual greenhouse gas emissions.

But while Adani wasn’t the first company to declare an interest, it is the only one to dig coal from the massive Galilee basin.

Success for Adani could mean opening up the entire basin for coal development.

After almost a decade – and an almost eight-year delay to the initial schedule for extracting coal – the company now says it has downscaled the project to about 10m tonnes. But Adani still holds approvals for those higher levels.

In some narratives, the Adani mine helped tipped the balance at the 2019 federal election. Final approvals from the state government were pending and Adani launched an advertising and letterboxing campaign criticising the Labor state government over its handling of the project.

Central and north Queensland marginal seats swung heavily to the Coalition and within days of the election, state Labor moved to hand Adani its required approvals, in some cases despite concerns from the government’s own experts about threatened species management plans.

Susan Harris Rimmer, the director of the Policy Innovation Hub at Griffith University, says the mine became emblematic of a broader debate about jobs and climate action in regional Queensland.

“Politicians up there use strong binary language,” she said.

“They’ll keep doing it, because it worked. It’s the same with immigration or terrorism. It works [as a political strategy] so people will fall back on it. There is a playbook, they’ll try it again.”

Harris Rimmer said the anti-Adani convoy, led by the former Greens leader Bob Brown, became a flashpoint and helped spread “us and them” rhetoric in parts of Queensland.

“I think that convoy became an image of people from the south, who lose nothing, making us [in regional Queensland] look like the villains.

“That’s what it looked like, I’m sure that’s not the way it was meant, but it looked like [people] coming to tell this stupid community not to do this.”

‘A crap moment’

In 2020, the Adani Group started to remove its own name from its Australian operations. First, the company renamed its Adani mining operations to Bravus.

Then it changed the name of the Adani Abbot Point Terminal, north of Bowen, to North Queensland Export Terminal (the words Adani and coal don’t appear on the corporate website).

“That name change definitely gave the impression the name Adani was becoming an impediment,” says Vincent. “If you’re confident in your brand you don’t change it to something else.”

Vincent says the campaign has had other knock-on effects well away from the Adani mine.

“It’s been the catalyst for dozens of financial institutions around the world to rule out thermal coal projects,” he says. “The risk of being associated with large [coal] projects has become reputational kryptonite.”

In May, fossil fuel producers complained to a parliamentary inquiry that campaigns against the industry were now making it harder to finance and insure major projects.

Adani told the inquiry it had been refused loans and insurance, and contractors and business partners had walked away.

In a submission, the company said “the boycotting of Australia’s thermal coal industry by Australian banks and insurance companies is misconceived and indifferent to the manifest damage their decisions will have on the industry’s ability to remain globally competitive” and it would impact Australia’s economy.

Vincent says while the first coal being shipped is “a crap moment for the campaign”, major financial groups continue to distance themselves from the project, joining scores of others.

Last month one of the world’s biggest banks cut ties with the project saying the venture is incompatible with its environmental, social and governance rules.

Activists

continue to target the project – locking themselves on to rail lines

and rolling stock and suspending themselves from cranes at the company’s

port. Two protesters clambered aboard one of the project’s trains this

week and spent a day allegedly shovelling coal over the side.

Separately, some Wangan and Jagalingou traditional owners have long opposed the project,

saying it will destroy their cultural lands and risk the sacred

Doongmabulla springs. The miner has a formal land-use agreement with the

Wangan and Jagalingou people but the agreement is opposed by some

traditional owners.

Traditional owners have been carrying out continuous cultural ceremonies on the mining lease for more than 90 days.

Adrian Burragubba, a traditional owner who has battled Adani for years, says Adani “should not be celebrating”.

Wangan and Jagalingou traditional owner Adrian Burragubba speaks during a rally at Queensland parliament in August. Photograph: Russell Freeman/AAP

His family and other traditional owners are concerned cultural sites with “literally thousands of artefacts” are being disturbed.

Burragubba says his son Coedy McAvoy has been on the land since 28 August performing ceremonies. “He declares he’ll remain there,” says Burragubba. “It’s our duty to take care of the land and monitor what the mining company is doing.”

Adani has been calling for the police to step in to remove McAvoy, as well as to take stronger action against different protesters targeting the railway.

In October, police told McAvoy and others camped on the company’s mining lease they would not remove them “at this time”.

Litmus test

The Australian Conservation Foundation, a member of the Stop Adani Alliance, successfully overturned federal approval for the mine’s water scheme earlier this year, with the issue still unresolved.

The ACF chief executive, Kelly O’Shanassy, said the campaign still had much to achieve. As insurers, financiers and contractors walked away, there were “still questions about the viability” of the project.

She says the group will work “incredibly hard” to stop the Galilee basin opening, but Stop Adani is a defining climate campaign.

“Your position on Adani indicated your position on climate, particularly politically. It became a litmus test.

“ACF has been switching the focus to escalating the clean future and we couldn’t have got people interested in that unless there was an end to coal and gas. I think we’ve won the public argument on that.”

Since the campaign against Adani began, the world’s financial markets have shifted away from coal. At the Glasgow climate summit, more than 40 countries agreed to phase out coal power.

“If we decide that in 2021 we cannot be adding more coal to the global market, then that’s a decision we have to hold ourselves to,” Vincent says.

Over the course of the campaign, there have been scores of other fossil fuel projects that have been announced, developed and approved. Did the focus on Adani shift the campaigns – and the eyes of the public – to just one spot in north Queensland?

“Even a dark firmament needs its darkest stars,” says David Ritter, the chief executive of Greenpeace Australia Pacific.

“The scale of the Galilee Basin demanded that attention.

“But the campaign drew attention to the overall issue and hopefully generated the kind of community enthusiasm to oppose [fossil fuel projects] everywhere else in Australia, not just at the Adani mine.”

The Guardian asked Adani Australia when it expected to export its first coal from the Carmichael mine and requested an interview with its chief executive, Lucas Dow.

A spokeswoman sent a short statement, saying: “The Carmichael Mine is on track to export coal in 2021.”

No comments:

Post a Comment