Extract from The Guardian

If the problem with Anthony Albanese is that he’s an unknown quantity, then the problem with Scott Morrison is that we know him all too well.

Morrison is hammering this because the observation has salience.

Voters in the marginal seats we’ve visited around the country say they don’t yet have a firm grip on the Labor leader, or his policy offering. The Labor campaign is taking a risk by not fleshing out their candidate – something I pointed out a month ago. The lack of definition around Albanese is, in fact, the bedrock of Morrison’s opening campaign pitch, which is better the devil you know.

Coming from Morrison, blank page is an ironic charge. He could easily be talking about himself in 2019. The last time Morrison faced an electoral contest, he donned a baseball cap and jetted around the country telling voters not to vote for Bill Shorten.

That was it. That was the pitch. The bill Australia can’t afford.

Morrison was the ultimate blank page. Apart from delivering tax cuts, what would happen during the prime minister’s first 100 days, or even the next three years, was a mystery to me in 2019, and I watch politics for a living.

Last time Morrison faced the people, he’d been prime minister for less than a year. After Malcolm Turnbull was bundled out of office, Morrison became Australia’s fifth prime minister in a decade. Four of the five had taken the job after a leadership spill. He wasn’t well known, and he certainly wasn’t fully fleshed out.

So this “blank page” narrative is not only self-serving, it’s hypocritical.

Being a blank page is also not a barrier to winning an election. Morrison himself is the proof point.

Morrison’s version of his record will doubtless be a cavalcade of achievements. But this telling will be selective, because the material is mixed.

Best to be direct. The worst of Morrison is right up there with the worst I’ve seen in two decades of political reporting. That’s the truth. Genuinely, terrible.

Let’s recap these past three years. After sailing back into government with no clear agenda, the government drifted. New MPs arriving served up an ideas boom. It wasn’t just the newbies. Frustration was building inside the government.

The frustration was about power without purpose. The economy was grinding, not thriving. There was angst about climate and energy policy and other hot button issues. Morrison was unhappy with the restiveness. As the months went on, the prime minister told the young and the restless to pull their heads in.

Then we hit the bushfires in late 2019-20. Morrison’s now infamous Hawaiian sojourn. Not holding a hose. The terrible body language in Cobargo. The inability to speak honestly and transparently about the obvious link between climate change and the catastrophe. That discordant interlude where a promotional video was issued on one of the most perilous days of the disaster. Morrison was in political freefall.

The coronavirus pandemic saved him, which seems an odd thing to say, given how much anxiety and adversity Morrison and his ministers faced, particularly over the first 12 months.

Morrison learned a critical lesson from the bushfires: don’t look impotent. He grabbed the second disaster and folded the premiers into a war cabinet. Morrison is task oriented. A pandemic generates an enormous number of tasks. The prime minister thundered through his daily to-do list like a man who would live and die politically by the decisions he was making.

During the first 12 months, he was rewarded for his pragmatism in the pursuit of saving lives and livelihoods. But in the second, things became more fraught, and not only because the government initially botched the procurement of life-saving vaccines.

Opinion polls suggested a majority of Australians were on board with the public health measures, and the government’s massive fiscal response minimised labour market scarring – an important policy achievement. But a vocal minority found the intrusions enraging. Some of the quiet Australians got noisy, and the pandemic, politically, for the Coalition transited from political plus to political risk.

As this played out, Morrison comprehensively botched his response to parliament’s #MeToo reckoning. The prime minister shrank, schemed and strategised when he should have listened, empathised and led.

He then dragged the Coalition into making a commitment to net zero emissions by 2050, which should have been one of his signature achievements, but he failed the future. Morrison discounted his own pivot by producing no credible policy to deliver the pledge. Humanity won’t be saved by a catchphrase. Ask the residents of Lismore.

Morrison ramped up the national security rhetoric, correctly identifying we live in the most dangerous geopolitical times since the second world war. But he also executed the Aukus agreement, which leaves Australia with a substantial defence capability gap, unless there’s something about this procurement the prime minister isn’t disclosing pre-election. In the process, Morrison enraged France, a significant Pacific power. In what remains an absolutely extraordinary geopolitical moment, Emmanuel Macron branded Morrison a liar.

There were the sports grants. The car park grants. Excoriations by the Australian National Audit Office. Morrison promised to deliver a federal anti-corruption watchdog and failed to deliver. Morrison also promised to protect religious freedom. That promise was whittled back to an anti-discrimination package that some of his own people refused to support because of their moral discomfort about allowing vulnerable transgender kids to become casualties of concocted woke wars.

I said earlier Morrison was a blank page in 2019.

Perhaps this isn’t quite right. Perhaps a better analogy is a mirror. To stay in power, Morrison disappeared behind a reflective surface and positioned Shorten in front of it.

When Morrison did present himself to the community, what they saw was themselves, because he mirrored them. Avuncular suburban dad who mans the barbecue all day at the school fete, with a cheery wife who does the carpool. Those endless, looping TV pictures – prime ministerial wallpaper. Hands on hips, head nodding, a consoling arm draped around a shoulder, a simulacrum of listening. A Christian for Christians, but not too churchy. Saturday night curry chef. Go Sharks.

All this probably sounds like I think Morrison will lose the coming election.

That’s not right actually. As this contest opens, I think it’s entirely possible, perhaps even likely, he’ll win.

Morrison is relentless on the stump. Labor’s pathway to victory is narrow. In the absence of outsized anti-government swings, Albanese will struggle to pick up seats in Queensland. There will also likely be a high non-major party vote. How will those preferences distribute?

So the devil you know might prove the winning pitch.

But voters are fatigued by Morrison’s shtick.

Polls show that. Vox pops around the country record the frustration. The Liberal candidates in marginal seats busily distancing themselves from him demonstrate that Morrison is a drag on their campaigns.

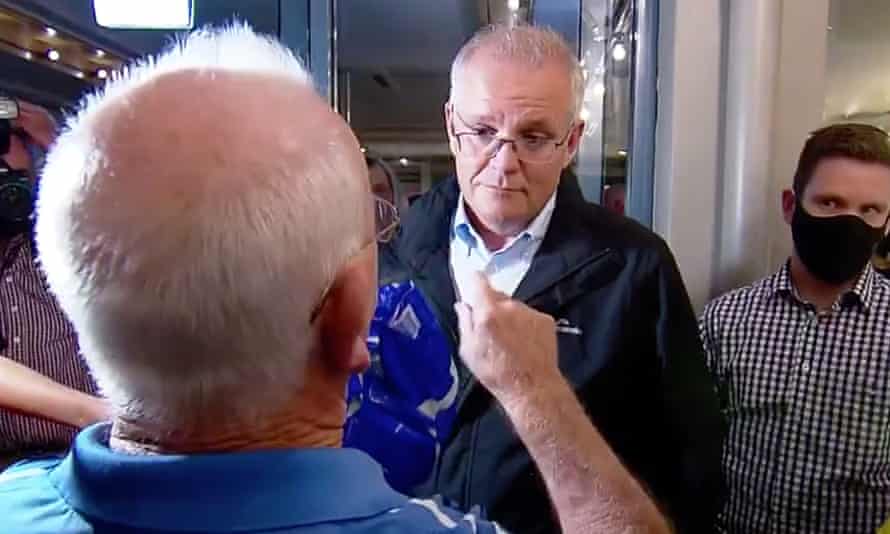

After three years of adversity, Australians lack appetite for a political circus. An impromptu excoriation Morrison copped on Thursday night from pensioner Ray Drury was potent because it nailed the prime minister’s chief vulnerability – the measurable gap between rhetoric and delivery.

In their darker moments, ambitious leaders wonder how things end. Is it with a stab in the back by a colleague? A loss to a lesser opponent? Because of happenstance, or events? Or does it end because Australian voters lack mercy when they believe a leader hasn’t met the moment? Political endings can be pitiless. The world shrinks until it’s just you, and the indignity of rejection, a loss so intense it transforms some discarded prime ministers into miserable ghosts.

Drury gave Morrison a harbinger of how public life can end this week. Drury told Morrison he had promised that people who had a go would get a go. “Well, I’ve had a go, mate, I’ve worked all my life and paid my taxes,” the pensioner said.

When Morrison tried to talk him down, Drury gave it to him straight: “You better fucking do something, I don’t care.

“I’m sick of your bullshit.”

No comments:

Post a Comment