Extract from The Guardian

Psychology researchers say health-related conspiracy theories appeal to but do not satisfy a need to make sense of the world.

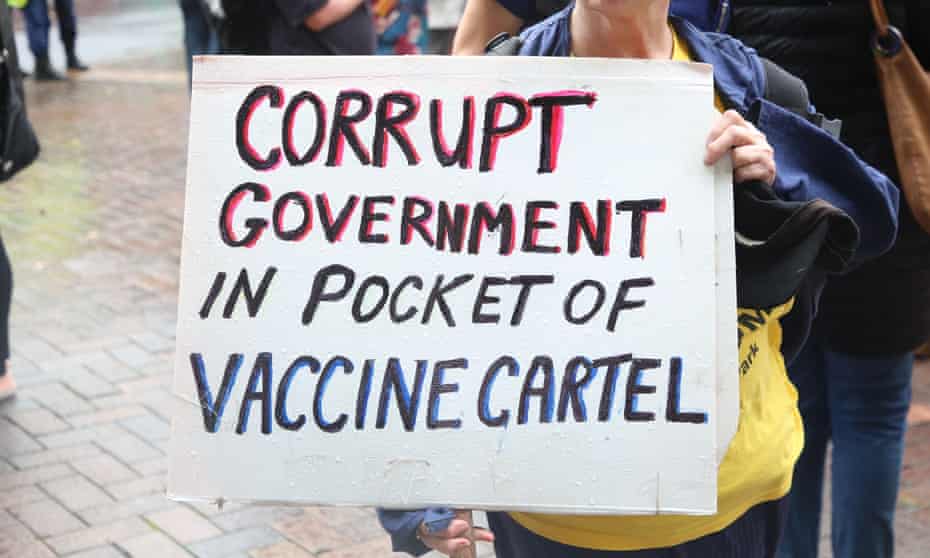

Medical misinformation has spread widely during the coronavirus pandemic, contributing to higher Covid death rates among the unvaccinated and causing frayed relationships between friends and family members with opposing views.

Writing in the Medical Journal of Australia, psychology researchers have suggested practical tips on how to talk to someone who firmly believes in health-related conspiracies.

Especially during times of social unrest or uncertainty, people may turn to conspiracies to explain large-scale events, said Dr Mathew Marques, a co-author of the paper and a lecturer at La Trobe University.

Conspiracy theories appeal to – but fail to satisfy – three universal psychological needs, according to the paper’s authors.

These include a “need to make sense of the environment around us … [and] an existential need to reduce the threat and the vulnerability faced in everyday life”, Marques said. “We know that people, when they’re made to feel more anxious, are more likely to believe in conspiracy theories.

“These underlying needs tend to better explain belief in conspiracy theory than … not rationally processing [things] or some sort of ‘faulty mechanism’ that in the past people have made suggestions [about].”

The researchers suggest listening empathically to individuals who believe in health-related conspiracies such as Covid-19 being a hoax. “Often, people’s reaction is to tell somebody that they’re wrong … or ridicule them. That’s not going to really cause anybody to change their mind,” Marques said.

Marques advocates “really trying to understand the motivations for when somebody’s speaking to you – whether it’s a patient or if it’s a close family or friend”.

“Maybe they’ve had a previous poor experience with medical authorities or practitioners, and so will be highly suspicious of those authorities and individuals.”

Other suggestions include making social contact and offering support to people that may help to redress a sense of lack of control in their lives. For someone who has lost a job, for example, aiding them financially could be helpful, Marques said.

For conspiracy believers who perceive themselves as critical thinkers, the researchers suggest it may be helpful to appeal to this characteristic and encourage thorough evaluation of information.

Evidence has also shown that “inoculating” people against misinformation before they are exposed to it – often called “pre-bunking” – can help prevent people falling for health conspiracies. The technique involves countering myths and lies before they are presented unopposed.

This can be challenging because specific conspiracies change over time, Marques said, but they often portray “a powerful group involved in a malevolent cover-up against an unsuspecting public”.

No comments:

Post a Comment