Extract from The Guardian

More and more Australian young people are entering adulthood with depression, debt and relationship breakdowns because of gambling in their youth.

Tue 3 Oct 2023 01.00 AEDT

Last modified on Tue 3 Oct 2023 07.25 AEDTHe remembers gambling away $500 in birthday money when he was 12. “I was late to school because I didn’t want to leave my computer,” he says.

Now 24 and living in Melbourne, he says the habit led to drug use, as well as mental health issues that he is “only just starting to recover from”.

A Guardian Australia investigation has revealed an increasing number of young people are entering adulthood with depression and anxiety, alongside debt and relationship breakdowns, because of gambling in their youth.

Data provided by Gambling Help Online revealed a 16% increase in the number of young people aged 24 and under contacting the help service in the 2022-23 financial year, with youth aged between 15 and 24 in Victoria accounting for about 600 of those 2,136 requests for help.

Public health experts say the data represents just a fraction of the young people being harmed, either from their own gambling or that of others. They have called for comprehensive bans on all forms of marketing for gambling products and say that trusting industries to self-regulate doesn’t work.

A joint study between Federation University and the coroner’s court of Victoria, released last month, found that between 2009 and 2016, 184 of 4,788 suicide deaths in the state were gambling related.

Fourteen of those were 17- to 24-year-olds.

More than monetary loss

Australians lose about $25bn on legal forms of gambling each year, according to the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare – the largest per capita losses in the world.

Children grow up with gambling enmeshed in the sports they play and watch, and the online environment offers innovative ways for gambling to be marketed to them. One study of Victorian secondary school students found almost a third had gambled in the previous 30 days.

Steven recalls first being exposed to gambling via influencers and advertisements in online video games. “People would also put gambling website links into their video game name to get extra credit on gambling websites,” he says.

“YouTube is very popular for influencers to promote gambling websites, and I’d watch other people gamble on YouTube using funds credited by the gambling website that sponsored them.”

Over the past decade, Deakin University’s Prof Samantha Thomas, a public health sociologist, has spoken with thousands of young Australians and their parents about gambling.

Children as young as eight find the content of gambling ads appealing and have high brand awareness and detailed recall of the content of those ads, her research has found.

“Celebrity endorsements, influencer endorsements and what we call risk-reducing promotions such as cash-back offers are having the most impact on young people, especially in terms of them thinking that gambling has no risk attached to it,” Thomas says.

“The gambling industry is one of the most agile, hi-tech, health-harming industries that we have probably ever seen.”

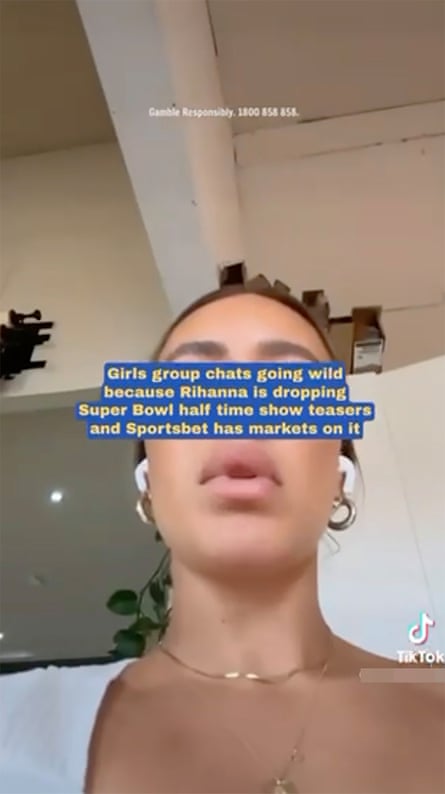

Thomas says gambling companies are constantly updating technology to enhance the social aspect of gambling. Innovations especially appealing to children include “chat with mates” functions within betting apps, and TikTok videos that subtly advertise betting by appearing as a sponsored post on children’s feeds.

‘If you have a debit card, you can bet’

Online video game casinos let gamers trade virtual items known as “skins” and “loot boxes” bought within video games for currency, and that currency can then be used to gamble.

“If you end up winning, you can use the website currency to buy virtual items to then sell for real cash,” Steven says. Some virtual items are considered so prestigious and uncommon that they have become a form of virtual currency that can be re-sold on secondary markets for thousands of real-world dollars.

“And if you lose the items, you can just buy more virtual items to gamble with,” he says. “It completely circumvents the 18-plus age requirement for gambling. I started gambling when I was 10 using these sites.”

James*, now in his early 20s and also from Melbourne, agrees it was easy to gamble money as a child – he started at 15.

“I had a part-time job at McDonald’s while I was at school, but also whenever I would receive money for things like lunches I’d often hold onto it,” he says. “There are no definite age restrictions on many gambling sites, and even if they say there are, if you have a debit card, you can bet.

“I don’t know if it directly led me to betting at the TAB, but I’m sure there is some correlation, with the dopamine receptors being reconfigured from a young age to feel a reward from gambling.”

Children also use the credit cards of adults to gamble, according to Helen Poynten, the Queensland regional manager for Relationships Australia. And because betting is such an ingrained part of Australian culture, Poynten says, parents are also downloading gambling apps and signing up on their child’s behalf to get around age restrictions.

Poynten says she was recently approached by a grandmother asking for help as her 13- and 14-year-old grandchildren had taken her credit card to use for online gambling, putting her $12,000 in debt. She didn’t want to report her own grandchildren to police, but was trying to pay the debt off on her pensioner income, Poynten says.

“She was devastated. I referred her into our Gambling Help Service. But she owns the debt.”

Conditioned to gamble as though it’s normal

Children and young people are not only gambling online. The Growing Up In Australia Longitudinal Study of children found the most common gambling activity for 16- to 17-year-olds was private betting with friends or family, but they also reported betting on sports games, and horse and dog races.

Despite proof of age being required for entry into gaming venues, about 9,000 teenagers who took part in the study reported having spent money on poker machines, casino table games and Keno. The Victorian Gambling and Casino Control Commission in September charged Tabcorp and eight venues for allegedly allowing a minor to gamble on 27 separate occasions.

A spokesperson from the NSW Office of Responsible Gambling said the primary mode of gambling reported by under-25s who reached out for help were poker machines and sports betting.

Jordyn*, who has gambled since the age of 14 and now works in the poker industry, says: “Some of our most regular clientele that are increasingly gambling in a way that concerns me are youth players under the age of 24.”

“Younger people I see are more likely to gamble more often and compulsively than I ever did, even at my worst,” the now 28-year-old says.

“They are much more likely to bet in smaller amounts every few minutes, with little thought.”

He says young people who play the poker games he runs often come in as groups of high-school or university friends.

“They play the pokies, roulette, blackjack et cetera as a social activity. They’re more likely to not buy dinner or beers, easily spending their money on gaming machines instead.”

Jordyn believes advertising by the gambling industry is leading to “hundreds of young, inexperienced gamblers placing bets they think are good bets but are in reality promotions that just get them further hooked”.

He says young people have been conditioned to gamble on pokies and betting tables in a rapid and reckless way by apps and websites where betting is instantaneous.

“By the time you’re 18, [opening an online or app-based betting account] is almost as easy as opening an email account,” he says.

“I’ve seen some absolutely braindead betting, such as teenagers betting on a random horse race in Korea because it just happened to be the next to jump. The ease of app betting does lead to a more compulsive and more social-focused gambling style than I’ve otherwise seen.”

‘I was in a trance’

Robbie*, now 24, says his addiction started at age 16 playing online games, acquiring skins and gambling with them online. “There was a night where I lost all my savings at the time, which was around $8,000,” he says.

“I was in complete despair and I felt as if my hands were moving by themselves, almost as if I was in a trance.”

He says that when he turned 18 he went to Crown casino with only $20, including the free $10 worth of table vouchers the casino gave to new members at the time.

“That night I came home with almost $1,000 in cash. In reality, the lucky ones are the ones that lose, as the real addiction hits harder on the ones that win. It is so hard to shake off and becomes a lifetime issue.”

Thomas says although her research with young people has found that they perceive gambling as “very normal”, they are also incredibly critical of the industry.

“They are particularly critical of the advertising strategies, but that doesn’t mean to say that they’re not influenced by them,” she says.

“And they are very aware that this is something that the government should be doing more about in order to protect them.”

It echoes findings from research under way by the Curtin University’s school of population health examining the impact of gambling industry marketing on young people.

In a series of interviews the researchers conducted with 12- to 17-year-olds, one young person said the gambling industry making donations to politicians was “like bribing a referee”.

Another young person told the researchers political donations from the gambling industry “shouldn’t be allowed because people should make decisions about restrictions and laws and stuff based on what they think is right, not on who is giving you the most money”.

Organisations and individuals linked to the gambling industry have made at least $80m in political donations to political parties across a 22-year period, an ABC investigation found last year.

Industry self-regulation ‘doesn’t work’

Prof Steve Robson, president of the Australian Medical Association, described youth gambling as “a massive public health problem”. “It needs to be taken very seriously, and independent regulation [is needed] that puts the vulnerable person who’s being harmed at the centre – rather than company profits.”

Curtin University’s Dr Jonathan Hallett says it is concerning that many governments don’t treat the gambling industry with the same urgency they do other harmful industries, such as tobacco, and allow the industry to make donations, self-regulate and develop their own harm minimisation strategies.

“Most of the time gambling is overseen by agencies focused on regulation rather than prevention,” Hallett says.

“It’s even more concerning when these bodies see the gambling industry as a partner in developing policy. Based on our experience with other harmful products, simply trusting industries to self-regulate doesn’t work. It can backfire or be used simply to delay effective regulation.”

Robbie says he wants governments to hold to account “these sites that take advantage of people and prey on people by giving them perks and rewards the more they wager”, so that other young people don’t face the debts and despair he did.

“I’d also like to also emphasise to the youth that wins from gambling are not worth the lifetime of struggle from addiction that is likely to come with it.”

* Names of young people interviewed have been changed to protect their identities

Are you a parent or teacher concerned about youth gambling? Tell us your experience

Gamblers Help: 1800 858 858. Other crisis support services can be reached 24 hours a day: Lifeline 13 11 14; Suicide Call Back Service 1300 659 467; Kids Helpline 1800 55 1800; MensLine Australia 1300 78 99 78; Beyond Blue 1300 22 4636

No comments:

Post a Comment