Extract from The Guardian

Future in which global concentration of C02 is

permanently above 400 parts per million looms

‘We’re going into very new territory’: James

Butler, of the US National Oceanographic and Atmospheric

Administration, says the amount of carbon dioxide is locking in

future warming. Photograph: John Giles/PA

Wednesday 11 May 2016 18.11 AEST

The world is hurtling towards an era when global

concentrations of carbon dioxide never again dip below the 400 parts

per million (ppm) milestone, as two important measuring stations sit

on the point of no return.

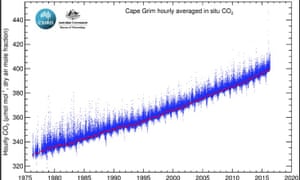

The news comes as one important atmospheric

measuring station at Cape Grim in Australia is poised on the verge of

400ppm for the first time. Sitting in a region with stable CO2

concentrations, once that happens, it will never get a reading below

400ppm.

An atmospheric

measuring station at Cape Grim in Australia is poised on the verge of

400ppm for the first time. Photograph: CSIRO

Meanwhile another station in the northern

hemisphere may have gone above the 400ppm line for the last time,

never to dip below it again.

“We’re going into very new territory,” James

Butler, director of the global monitoring division at the US National

Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration, told the Guardian.

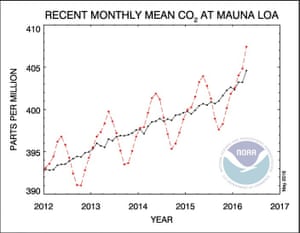

In Hawaii, the Mauna

Loa station is sitting above 400 ppm and might never dip below it

again. Photograph: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

The first 400ppm

milestone was reached in 2013 when a station on the Hawaii’s

volcano of Mauna Loa first registered a monthly average of 400ppm.

But the northern hemisphere has a large seasonal cycle, where it

increases in summer but decreases in winter. So each year since it

has dipped back below 400ppm.

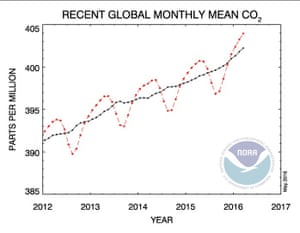

Then, combining all the global readings, the

global monthly average was

found to pass 400ppm in March 2015.

A National Oceanic and

Atmospheric Administration graph of global monthly mean carbon

dioxide. Photograph: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

In the southern hemisphere, the seasonal cycle is

less pronounced and atmospheric levels of CO2 never drop, merely

slowing in the winter months. This week scientists revealed

to Fairfax Media that Cape Grim had a reading of 399.9ppm on 6

May. Within weeks it would pop above 400ppm

and never return.

“We wouldn’t have expected to reach the 400ppm

mark so early,” said David Etheridge, an atmospheric scientist from

the CSIRO, which runs the Cape Grim station. “With El Nino, the

ocean essentially caps off it’s ability to take up heat CO2 so the

concentrations are growing fast. So we would have otherwise expected

it to happen later in the year.

“No matter what the world’s emissions are now,

we can decrease growth but we can’t decrease the concentration.

“Even if we stopped emitting now, we’re

committed to a lot of warming.”

Over in Hawaii, the Mauna Loa station, which is

the longest-running in the world, is sitting above 400 ppm, and for

the first time, might never dip below it again.

“It’s hard to predict,” Butler told the

Guardian. “It’s getting real close.”

Meanwhile, the global average, after controlling

for the seasonal cycle, popped above 400ppm late last year. Within a

couple of years, the seasonal dips will never drop below 400ppm in

the global average too.

Air samples collected at Cape Grim, Tasmania,

Australia, under clean air (baseline) conditions. Photograph: CSIRO

All together, the world is on the verge of no

measurements ever showing a reading under 400ppm.

“There’s an answer to dealing with this and

that’s to stop burning fossil fuels,” Butler said.

Butler also emphasised that this CO2 is locking in

future warming. “It’s like lying in bed with your electric

blanket set to three. You jack it up to seven – you don’t get hot

right away but you do get hot. And that’s what we’re doing.”

The CO2 concentrations are driving what appears to

be runaway climate change around the world.

This year has seen record hot global ocean

temperatures, which have caused coral reefs all around the world to

bleach and devastated Australia’s Great Barrier Reef.

Air surface temperatures have also been shocking

climate scientists. Yearly and monthly temperature records have been

breaking regularly, with many of the records being broken by the

biggest margins ever seen.

“It’s pretty ugly when you look at it,”

Butler said.

No comments:

Post a Comment