Extract from The Guardian

The One Nation senator dismisses the conventional

scientific view of climate change. Here are the holes in his most

commonly deployed arguments

One Nation senator Malcolm Roberts argues that all

the major science organisations around the world have collaborated,

manipulating climate data to suppress temperatures in the 1930s and

40s, thereby making today’s temperatures look unusual. Photograph:

Phil Noble/Reuters

Wednesday 14 September 2016 10.33 AEST

The election of Malcolm Roberts as a One Nation

senator has put Australia’s media in a difficult spot.

In his first

speech to Parliament on Tuesday, Roberts made many false claims

about climate change. He said that climate change was a “scam”

and implied that it was some sort of conspiracy between all the major

international research agencies. “ ... there is no data proving

human use of hydro-carbon fuels affects climate,” he said.

Most news outlets had stopped covering the views

of climate science deniers in regular reporting. There is a clear

scientific consensus that the world is warming and that human carbon

emissions have caused it, so reporting the views of a few non-experts

who push fanciful theories with no credible evidence is seen as

“false balance”.

But journalists are in a different position when

someone in an important office holds such views.

Discussing whether the Guardian would publish

letters from climate change deniers, the readers’

editor wrote in 2013: “Sometimes the identity of a person

expressing an opinion is as interesting as the thing being expressed.

If a member of the royal family wrote a letter denying that climate

change exists the Guardian would almost certainly run it.”

Some have argued the media should ignore the views

of Roberts. But as a senator his views may affect legislation and the

terms of the debate that influence it. So those views are newsworthy,

particularly in the early part of his term when many Australians will

be becoming aware of him for the first time. Guardian Australia will

report them when that is warranted on grounds of public policy

debate.

But to avoid repeatedly having to debunk Roberts’

views, we have produced a handy reference list of his main arguments,

as

outlined on the ABC’s Q&A program on 15 August. This list

may be updated if he introduces new elements to back his claims.

One Nation’s Pauline Hanson with fellow senator

Malcolm Roberts, who is a climate science denier. Photograph: Dan

Peled/AAP

The ‘pause’

Another inconvenient fact, temperatures statistically have not been warming since 1995

One main strategy used by climate change deniers

is to argue that there is no trend in warming, or that the recent

trend is not at all unusual.

They often point to what has been called by some a

“pause” in global warming – also sometimes called the “hiatus”

or “slowdown”. They point to temperatures in 1998 (or sometimes

a bit earlier) and say they were similar to today’s

temperatures. They conclude that therefore global warming has

stopped.

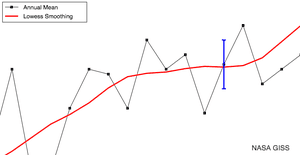

If you look just at the temperatures in the graph

below, ignoring the red trend line which is averaged over longer time

periods, there doesn’t seem to be much warming.

Global surface air and sea surface temperatures

between 1998 and 2013. Photograph: Nasa

The most obvious thing wrong with this argument is

that no climate scientist thinks global warming means temperatures

will always increase at the same rate. The climate has many natural

sources of “variability”, which push temperatures up and down

over months, years and decades. Superimposed over global warming,

that variability can speed up or slow down the warming trend we see.

Short periods of slower cooling are expected as a

result of weather events such as La Niña.

This probably happened between 1998 and about 2013

(although some scientists have controversially suggested

it may not have happened at all). 1998 was a record hot year, and

if you look only at the 15 years that followed, temperatures didn’t

increase much.

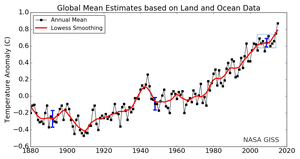

Of course, choosing a record hot year as your

starting point is cheating – just as choosing a record cold year

would be. When you zoom out and look at the longer-term picture,

there is a clear trend. And since 2013, temperatures have

skyrocketed, with 2014 and 2015 (and almost certainly 2016) each

setting new records.

Global surface air and sea surface temperatures

since 1880. The blue box indicates the small region used to suggest

global warming had stopped. Photograph: NASA

Understanding the precise causes of that short

period of slower warming was of interest to scientists but it was not

a challenge to the general picture that the globe was warming – and

continued to warm – on larger timescales.

For what it’s worth, a lot of work suggested the

“hiatus” was a result of an extended La Niña-like period in what

is called the Pacific decadal oscillation, in which heat from the

atmosphere was being stored just under the surface in the Pacific

Ocean. That process now looks as though it has reversed, releasing

the heat and causing a sharp temperature rise.

‘Manipulation’ of the data

MALCOLM ROBERTS: Yeah, 1930s and 40s were warmer than the current decades … The original records are … first of all, that the data has been corrupted and we know that the 1930s were warmer than today.

BRIAN COX, fellow Q&A panellist and physicist: What do you mean by corrupted? Corrupted? What do you mean corrupted?

ROBERTS: Been manipulated.

COX: By who?

ROBERTS: By Nasa.

COX: Nasa?

ROBERTS: Yes.

This is an example of two strategies in one. The

first is to deny there is a warming trend, or that it is unusual, as

in the “hiatus” claim.

When scientists point out that the data

contradicts the claim, climate change deniers sometimes resort to

conspiracy theories. In this case, Roberts argues that all the major

science organisations around the world have collaborated,

manipulating climate data to suppress temperatures in the 30s and

40s, thereby making today’s temperatures look unusual.

The weird thing here is that Roberts isn’t even

getting the conspiracy theory right. The theory he is thinking of –

which even most climate change deniers now reject – is not that

global temperatures were higher in the 30s and 40s, but that

specifically temperatures just in the US were higher than today.

Climate scientists used to believe that was the

case. Even then, they knew the world as a whole was warming, so the

scientific discussion revolved around trying to explain the spatial

variation – why temperatures in the US were different. It was in no

way a challenge to the clear observation that global temperatures

were rising sharply.

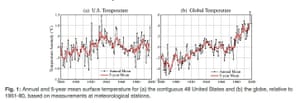

The chart below is from a paper

published in 1999 discussing this issue and comparing the known

global temperature rises with the understanding of US temperatures at

the time.

Graphs from a 1999 Nasa paper comparing how

scientists then interpreted US temperatures with global temperatures.

The problem was, records going that far back are

based on all sorts of measurements that are difficult to compare –

some are taken at different times of day or at different altitudes.

And many locations or times change over the period.

Figuring out how to put them all on the same scale

involves complex calculations. More than 15 years ago, Nasa’s

method of doing so resulted in the conclusion that US temperatures

were unusually high in the 30s and 40s.

Then Nasa expanded the data set it used to include

information about ocean temperatures and corrected for the then

well-documented “urban

heat island” effect.

The changes didn’t alter the trend much but did

mean that the hottest year on record in the US became 1998 rather

than 1934. As data and understanding improved, further adjustments

were made by Nasa in 2011, which revealed more of a warming trend

across the US.

All the changes were

discussed by Nasa at the

time but more than a decade later climate deniers picked this up

and claimed it was a conspiracy.

There is no such thing as meaningful raw data when

it comes to historical temperature records – they must be

interpreted. With more data and better understanding, that

interpretation will change. And since several different organisations

around the world do their own interpretations of the data and agree

on the outcome, confidence in their results can be high.

In any case, Roberts’ claim that global

temperatures were higher in the 30s and 40s is not even a conspiracy

theory that is held by anyone. And the claim that Nasa secretly

manipulated data to hide the fact that those decades were warmer than

today in the US is plainly false.

Even if temperatures in the US were higher then

than they were recently – as scientists thought in 1999 – it

wouldn’t change the global picture, which for a long time has

clearly shown increasing temperatures.

Trashing the models

The models have already been proven wrong, hopelessly wrong.

The truth is that climate models have been shown

to work remarkably well.

Models predict trends in climate, not particular

events. So a few years – even up to a decade or so – that isn’t

quite what a model predicted is not evidence the model is flawed.

But the performance of climate models over the

past few decades has been amazingly accurate.

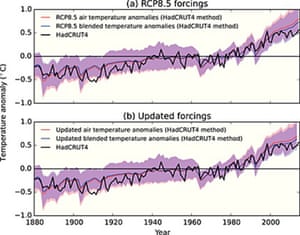

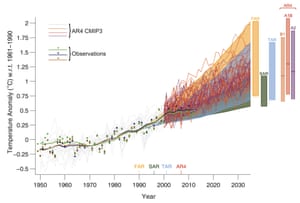

The image below comes from the latest report of

the UN’s intergovernmental panel on climate change. It shows how

observations

of temperatures have compared with climate models since 1990.

There are a lot of graphs floating around the

climate denier corners of the internet that cherry-pick some of the

observations and compare them with just some of the model

simulations, and usually don’t include the shading to show the

uncertainty in those projections.

Between 1998 and 2013, the observed temperatures

were towards the lower end of the models’ predictions. That is not

surprising, and it doesn’t mean the models aren’t working – the

temperature rise has still been within the expected range.

But a

paper last year showed the difference between prediction and

observation has been exaggerated, since while models are all about

surface air temperatures, the observations they were compared with

have traditionally been a combination of air temperatures over land

and sea surface temperatures, which are warming more slowly than the

air above the seas.

Correcting for that created a model that let

scientists to compare apples with apples, which showed the difference

between the simulation and observations shrank considerably. That can

be seen in the image below, where in the lower panel the shaded area

drops a bit lower, putting the observed temperatures closer to the

centre of the modelled temperatures.

The difference that was left was likely to be

simply a result of natural variability, which caused warming to slow

slightly and temporarily.

Before (top) and after (bottom) adjusting the

models so they projected temperatures in a way that could be compared

like-for-like with observations. Photograph: Schmidt et al. (2014)

Historical distractions

The latest warming cycle in the 17th century going into the 18th century was faster and greater than the latest warming …

It’s not clear what Roberts is talking about

here.

In the northern hemisphere there was a period of

relatively cold weather between about 1550 and 1800, known as the

“little ice age”.

No recent or even outdated studies suggest it was

warmer around 1700 than it is today. One book from 1965 – one of

the first works to suggest there was a “little ice age” – did

suggest some rapid warming towards 1700 in the northern hemisphere as

the world emerged from the cold period. But that was based on very

limited data and, even in that work, temperatures were not thought to

have risen to unusual heights. And newer work based on much more

detailed records suggests any cool period at roughly that time was

much less pronounced than previously thought.

This statement highlights another strategy used by

climate deniers. Making a spurious claim about temperature records

attempts to put the onus of proof on the interlocutor. It is so

unclear what Roberts is talking about that it is hard to make a case

against him.

‘It’s basic’

It is basic. The sun warms the earth’s surface. The surface, by contact, warms the moving, circulating atmosphere. That means the atmosphere cools the surface. How then can the atmosphere warm it? It cannot. That is why their computer models are wrong.

It’s honestly just not clear where to start with

this quote. Is he doubting that the sun can warm the atmosphere? If

so, then why is the atmosphere not freezing? Is he arguing that

because the earth’s surface is warmer than the air above it (which

is true over land), that the atmosphere can’t warm?

How should the media cover Roberts’ claims?

Media outlets are drawn in two competing

directions when deciding how to cover Robert’s false claims.

On the one hand, it has become common practice not

to report climate change denier views as a matter of course. And so

editors might be drawn to ignore his claims. But as discussed above,

his views could now have relevance and importance – not because

they are potentially true, but because they could influence the

workings of parliament.

On the other hand there can be the opposite drive

too. His views can be such good fodder for headlines, that there is a

temptation to cover everything he says. But taking that path allows

politicians to manipulate the media, driving them to say even more

outrageous things to garner even more headlines.

Roberts’ views should simply be reported when

they are newsworthy, no more and no less. Of course this can be a

tricky thing to judge, but newsrooms should be experienced at making

such decisions.

No comments:

Post a Comment