Extract from The Guardian

Often referred to as Earth’s evil twin, Venus is

the solar system’s hottest planet. But research suggests that Venus

may have had vast oceans and a balmy climate

Artist’s concept of lightning on Venus. The

Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency’s Venus Climate Orbiter mission

is observing the planet’s weather system in unprecedented detail.

Illustration: ESA/ Christophe Carreau

Hannah

Devlin Science correspondent

Monday 17 October 2016 21.37 AEDT

Its surface is hot enough to melt lead and its

skies are darkened by toxic clouds of sulphuric acid. Venus is often

referred to as Earth’s

evil twin, but conditions on the planet were not always so

hellish, according to research that suggests it may have been the

first place in the solar system to have become habitable.

The study, due to be presented this week at the at

the American Astronomical

Society Meeting in Pasadena, concludes that at a time when

primitive bacteria were emerging on Earth, Venus may have had a balmy

climate and vast oceans up to 2,000 metres (6,562 feet) deep.

Michael Way, who led the work at the Nasa Goddard

Institute for Space

Studies in New York City, said: “If you lived three billion years

ago at a low latitude and low elevation the surface temperatures

would not have been that different from that of a place in the

tropics on Earth,” he said.

The Venusian skies would have been cloudy with

almost continual rain lashing down in some regions, however. “So

while you might get nice sunsets you would have mostly overcast skies

during the day and precipitation,” Way added.

Crucially, if the calculations are correct the

oceans may have remained until 715m years ago - a long enough period

of climate stability for microbial life to have plausibly sprung up.

“The oceans of ancient Venus

would have had more constant temperatures, and if life begins in the

oceans - something which we are not certain of on Earth - then this

would be a good starting place,” said Way.

Other planetary scientists agreed that, despite

the differing fates of the two planets, early Earth and Venus may

have been similar.

Artist’s impression

of an active volcano on Venus. The Akatsuki mission could answer

longstanding questions, such as whether the planet has volcanic

activity. Illustration: ESA/AOES

Professor Takehiko Satoh, who works on the Japan

Aerospace Exploration Agency’s Venus Climate Orbiter

(“Akatsuki”) mission, said: “Habitable or not, I’m not in a

position to answer. Environment-wise, probably Venus once had an

ocean and probably the environment of Venus and the Earth might have

been similar.”

With an average surface temperature of 462C

(864F), Venus is the hottest planet in the solar system today, thanks

to its proximity to the sun and its impenetrable carbon dioxide

atmosphere, 90 times denser than Earth’s. At some point in the

planet’s history this led to a runaway greenhouse effect.

Previous US

and Soviet landers sent to Venus have survived only a few hours

on the surface before being destroyed.

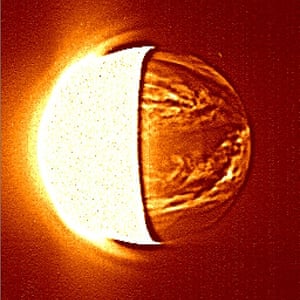

A image of the Venus’ night-side produced by the

Akatsuki mission. Photograph: JAXA

Way and colleagues simulated the Venusian climate

at various time points between 2.9bn and 715m years ago, employing

similar models to those used to predict future climate change on

Earth. The scientists fed some basic assumptions into the model,

including the presence of water, the intensity of the sunlight and

how fast Venus was rotating. In this virtual version, 2.9bn years ago

Venus had an average surface temperature of 11C (52F) and this only

increased to an average of 15C (59F) by715m years ago, as the sun

became more powerful.

More precise measurements of the chemical makeup

of Venus’s surface and atmosphere could help establish how much

water the planet had in the past, and when this began to disappear.

Some of this information may be filled in by the

Akatsuki mission, which is observing the Venusian weather systems in

unprecedented detail. The spacecraft was supposed to enter orbit

about the planet in 2010, but after its main engine blew out, it

instead spent five years drifting around the sun like a miniature

artificial planet. Last year, scientists used altitude thrusters to

redirect it into an orbit, and the mission could yet answer

longstanding questions about our planetary neighbour, including

whether it has volcanic activity, whether lightning strikes in the

sky and why its atmosphere is rotating 60 times faster than the

planet itself.

However, searching for traces of ancient microbial

life would need a lander, and would be significantly more

challenging.

“It would take a great deal of technology

development, and money of course, to build the requisite landing

craft to survive the surface conditions of present day Venus and to

be able to dig into the surface,” said Way. “But if the

investments were made it would be possible to search for such signs

of life, including chemical traces.” Details of the study are also published in the

journal Geophysical

Research Letters.

No comments:

Post a Comment