Australia

came late to the game. Since 1948, Americans have been polled after

each election to find out why they voted as they did. The Swedes started

to take these national snapshots in the 1950s and the British in the

1960s. Belfast-born Ian McAllister began the Australian Election Study

after Bob Hawke’s third victory in 1987. From his post at the

Australian National University – where these days he is Distinguished

Professor of political science – McAllister has conducted a dozen of

these big, after-the-event surveys over 30 years. “We ask how people

made their choices: the effect of the election campaign, the effect of

the longer-term predispositions, the background characteristics, the

political socialisation. It’s about trying to unravel all of these

various things that come together to make simply a choice on a ballot

paper.”

McAllister’s questions are controversial. The political science industry feeds off the Australian Election Studies. Dinner parties break up in confusion as pollsters and academics bicker over questions asked and not asked. McAllister told me: “If I put in every question that everybody emailed me or wrote to me about, you’d have a thousand-page questionnaire and nobody would fill it in.” He says the point of the surveys sent to thousands of voters after each poll is continuity. “When you’ve got exactly the same question being asked consistently over a period of time using essentially the same methodology, you’ve got an unusually reliable measure of something.”

The Australian voter is a species he has come to admire deeply. “First of all they have to go to the polls more than any other voter in the world that I can possibly imagine. And secondly they have to deal with a range of complexity in electoral systems, in terms of casting a vote, which again defies anything in any other society. So the Australian voter, I think, is pretty overburdened by politics.” Yet they remain thoughtful. “People don’t make whimsical choices by and large. They do look at policies.” They are not volatile. “We found in our surveys early in the piece about 70% of people never ever change their vote from the very first election they voted in to the last election before they died. These days it’s around about 50%. So basically most people don’t change. And when people do change it’s a relatively small proportion that change from election to election.”

That we’ve been so stable makes McAllister particularly alert to “the unexpected long-term decline” of trust in the political class, in career politicians, in democracy itself. “Australia has stood apart from a lot of other countries because it’s had very high levels of satisfaction with democracy historically, some of the highest in the world, second only to one or two Scandinavian countries.” He dates the slide from 2010. Elections since then haven’t provided the usual upswings of faith and hope. The numbers have kept falling. “One of the things I observe in our surveys is the proportion of people that believe the government would have a positive effect on the economy in the future year was at its lowest level we’ve ever recorded in 2016. So people don’t have confidence in the government … They see this quick turnover in leaders. They see scandals to do with expenses, and so on. And they become very jaded. And then I think we’ve had a lack of decisive leadership as well. I mean Rudd Mark I was the last popular leader that existed in Australia. We haven’t had one since.”

McAllister’s questions are controversial. The political science industry feeds off the Australian Election Studies. Dinner parties break up in confusion as pollsters and academics bicker over questions asked and not asked. McAllister told me: “If I put in every question that everybody emailed me or wrote to me about, you’d have a thousand-page questionnaire and nobody would fill it in.” He says the point of the surveys sent to thousands of voters after each poll is continuity. “When you’ve got exactly the same question being asked consistently over a period of time using essentially the same methodology, you’ve got an unusually reliable measure of something.”

The Australian voter is a species he has come to admire deeply. “First of all they have to go to the polls more than any other voter in the world that I can possibly imagine. And secondly they have to deal with a range of complexity in electoral systems, in terms of casting a vote, which again defies anything in any other society. So the Australian voter, I think, is pretty overburdened by politics.” Yet they remain thoughtful. “People don’t make whimsical choices by and large. They do look at policies.” They are not volatile. “We found in our surveys early in the piece about 70% of people never ever change their vote from the very first election they voted in to the last election before they died. These days it’s around about 50%. So basically most people don’t change. And when people do change it’s a relatively small proportion that change from election to election.”

That we’ve been so stable makes McAllister particularly alert to “the unexpected long-term decline” of trust in the political class, in career politicians, in democracy itself. “Australia has stood apart from a lot of other countries because it’s had very high levels of satisfaction with democracy historically, some of the highest in the world, second only to one or two Scandinavian countries.” He dates the slide from 2010. Elections since then haven’t provided the usual upswings of faith and hope. The numbers have kept falling. “One of the things I observe in our surveys is the proportion of people that believe the government would have a positive effect on the economy in the future year was at its lowest level we’ve ever recorded in 2016. So people don’t have confidence in the government … They see this quick turnover in leaders. They see scandals to do with expenses, and so on. And they become very jaded. And then I think we’ve had a lack of decisive leadership as well. I mean Rudd Mark I was the last popular leader that existed in Australia. We haven’t had one since.”

Ever since McAllister gathered the first set of One Nation numbers in 1998, political scientists have been disputing what they mean. Do they show people flocking to Pauline Hanson because of the flags she flies – particularly on race – or are they falling in with her simply because they’re disenchanted with the political system? McAllister sees a shift from one to the other: “My sense this time is that ONP#2 doesn’t really stand for much, other than being anti-establishment, whereas ONP#1 had a more definable policy basis. So Pauline Hanson is tapping into the prevailing political distrust in career politicians from both sides.” But others citing the same material come to the opposite conclusion. More of this dispute later. It’s fundamental to understanding the challenge Hanson poses to public life in this country. Is she a party of policy or protest? Hanson is a puzzle with consequences.

National background

Liberal 78% native-born

Labor 79%

Greens 82%

National 91%

One Nation 98%

Age and sex

One Nation is a party of old people but there’s no sign they are dying out. According to the AES figures, roughly a third of Hanson’s voters in 2016 were under the age of 44. And women are voting One Nation. Back in the 1990s, voters were mostly men. That’s shifted. Here’s the split:1998 male 65%, female 35%

2016 male 56%, female 44%

Reports from focus groups suggest these are working women, better educated than the men. “They looked like nice Labor voters working in nice jobs,” said one researcher. “We had a childcare worker, two government workers, and I think there was a teacher. Yet they like Pauline.” Other reports from focus groups suggest contradictions here: “Women like her because she’s a woman who speaks her mind. Men like her because she’s a woman who stands up against feminism.” That she’s a woman from the “life doesn’t owe us anything” school is a key aspect of her political makeup. Raising four children from two husbands hasn’t softened her heart towards single mothers. Twice divorced, she backs men burnt by the divorce courts. She opposes extending paid parental leave by two weeks: “They get themselves pregnant and have the same problems did with the baby bonus, with people just doing it for the money.”

Class

Most One Nation voters see themselves as working class. McAllister calls that “pretty clear”. This hasn’t changed in 20 years. Hanson’s people may have aspirations but they don’t see themselves coming up in the world.Greens 24% identify as working class

Liberal 32%

Labor 45%

National 46%

One Nation 66%

Religion

Hanson is not pulling the religious vote. Rebecca Huntley, social researcher and former director of Ipsos Australia, says: “We’re a little shielded from the worst implications of the rise of the Trump vote by the fact that this is not a highly religious group.” Hanson’s staunch defence of Christianity in the face of Muslim hordes isn’t about faith but preserving our way of life. Hanson’s moral agenda is to punish welfare bludgers not perverts. One Nation voters rarely worship. While 48% of Australians never attend church – not even for weddings and funerals – the figure for One Nation voters is 60%. Breakaway Cory Bernardi is pursuing a tiny constituency who believe in small government and high Catholic morality. Hanson backs neither: she’s a secular, big government woman. That’s a big constituency.Where do they live ?

Both the city and the bush. One Nation has always had a strong city presence despite its image as a bush party. Labor party research and focus groups report strong growth of support for One Nation in seats on the fringe of big towns and capital cities, seats on the edge of – but not actually among – migrant suburbs. This appears to be a pattern across Australia. On the edge of Sydney in 2016, One Nation picked up more than 6% of the Senate vote in Lindsay (75% Australian-born) but only 3% a few kilometres away in Greenway (58% Australian-born). In Lindsay they have fears rather than experience. As one researcher told me: “When you probe for personal experiences on anything they say about welfare or immigration, it’s always second- and third-hand.”How educated are they? Then and now, the figures show the typical One Nation voter didn’t finish school. Yet they are not unqualified. They make an effort. Tradespeople are strongly represented in party ranks. But eight out of 10 have never set foot on a university campus. “That’s the big political effect,” says McAllister.

That about eight out of 10 One Nation voters dropped out of school doesn’t mark them as dumb. Queensland, the party’s heartland, made it extraordinarily hard for a long time for poor kids to get to university. But for whatever reason, few of Hanson’s people have been exposed to life and learning on a campus. Huntley wonders if “the persistent attachment to clearly illogical connections between, say, asylum seekers and crimewaves, and also the interest in non-official online content, is because they never had never had at least some exposure to what happens at higher education”. What strikes her in focus groups is the One Nation attitude: “I can work this all out by myself.”

Have they been ruined by globalisation?

No. They are in work and middling prosperous. They aren’t on welfare. McAllister’s figures suggest there’s nothing particularly special about the pattern of employment for Hanson’s people. One Nation voters are no more likely to be at the bottom of the management heap than anyone else. There’s a tiny – and perhaps unreliable – skew away from government employment. McAllister says, “That’s a reflection of the fact that they tend not to have higher education.”But Hanson’s people are oddly gloomy about their prospects. One of the questions always asked in the AES is: “How does the financial situation of your own household compare with what it was12 months ago?” This is the breakdown by party of those who thought things were now “a little” or “a lot” worse for them than a year ago:

National 25%

Greens 27%

Liberal 29%

Labor 38%

One Nation 68%

The same gloom is apparent when Hanson’s people are asked about the state of the economy. This is the breakdown of those who thought the national economy was “a little” or “a lot” worse than it was a year ago:

National 35%

Greens 44%

Labor 46%

Liberal 47%

One Nation 73%

So while there is a lot of gloom about, Hanson’s people see the national economy going to hell in a handcart. Why?

The standard explanation – that these are people left behind by globalisation – works for Trump’s voters and is strong in the mix with Brexit. But it seems not a decisive component of the Hanson vote. This country weathered the global financial crisis in good shape. There is not a ruined class who lost their houses and savings in the crash. Employment held up. Economic growth since has been better in the cities – where half Hanson’s voters live – than the country, but her people are in work. Focus groups say many One Nation voters are working part time when they would like to be full time. Many worry about losing their jobs because they fear a new job will be hard to find. But sheeting those fears home to the ravages of free trade is difficult. Queensland is a free-trade state. Key to every trade deal this nation has signed in the last few decades is attempting to open world markets to coal, cattle and sugar. Nor does general nervousness about employment distinguish these voters from very many Australians. If Hanson were the natural choice of those wishing they had a better job and fearful of losing the one they have, she should be commanding divisions, not battalions.

The exaggerated gloom of One Nation voters in the 2016 election goes to something deeper than the economy. One Nation is the nostalgia party. “Simply addressing economic inequality – which is what the left has tried to do – is just not sufficient,” says Huntley. “Prosperity is important, but what worries this group is the cultural, social slippage they feel in their life. They imagine their fathers’ and grandfathers’ lives were better, more certain, easier to navigate. Maybe they were and maybe they weren’t, but it’s the loss of that that is worrying for them. The economic argument alone isn’t persuasive for them.”

But of course it has to be addressed. “If they think that a political party is representing their economic interest, they will vote for that party,” says Kosmos Samaras, assistant state secretary of the Labor party in Victoria. “But if the party doesn’t, they’ll vote on other interests.” By that he means alienation and hostility to immigration. “They feel, ‘I’m getting screwed anyway, so I’m just going to turn up to vote and fuck them.’”

Immigration

The numbers are powerful. Twenty years ago Hanson’s people were hostile to immigration. Now they are extraordinarily so. One Nation is the party of those not bought off in the end by Howard’s great Faustian pact: close the borders to boat people and the nation will relax about mass immigration. More than 80% of One Nation voters considered immigration “extremely important” when deciding how to vote. It’s a number that puts Hanson’s party way outside the pack:Greens 40%

Labor 43%

Liberal 49%

National 54%

One Nation 82%

More than

80% of One Nation voters also want immigration numbers cut. The

wishes of the party are now even more extreme than they were 20 years

ago. In 2016 the AES turned up only a single One Nation voter happy

to see immigration increased. The numbers all went the other way.

This puts Hanson’s people dramatically at odds with the sentiment

of a welcoming country. Here are those in each party calling for

immigration numbers to be cut “a lot”:

Greens 7%

Labor 21%

Liberal 24%

National 32%

One

Nation 83%

Their grim attitudes to migrants also set Hanson’s people apart. For One Nation voters, there is little disagreement that migrants increase crime, are not good for the economy and take the jobs of native-born Australians.

Those in each party who “agree” or “strongly agree” that migrants:

Greens 10%

Labor 55%

Liberal 63%

National 63%

One Nation 90%

One Nation is an anti-immigration party. There are, as we will see, a handful of other causes that unite Hanson’s people. But behind all the complex calculations about what drives people into Hanson’s arms, these figures speak with unmistakable clarity: One Nation voters loathe immigrants. It’s an embarrassing challenge for a decent country to find such forces at work, but it is much too late to pretend that a party which displays such extreme hostility to immigration is not driven by race. That’s simply not facing facts.

Anger with government

One Nation is the Pissed Off with Government Party. It was so the last time, when Australians still trusted their governments. In those days, being ignored by politicians was the base complaint of the party. Hanson was the gutsy politician who listened. Twenty years later, with trust in government sagging across the country, One Nation is coming into its own as the party that accuses politicians of not listening. It’s the brand.Nothing beats the hostility of Hanson’s voters here. This is the party breakdown of those who believe politicians “usually look after themselves”:

National 39%

Liberal 40%

Labor 51%

Greens 51%

One Nation 85%

McAllister rates this number “real and something worth focusing on”. He sees it as a measure of general dissatisfaction, not with government so much as the political class. “This taps into Brexit, Trump, Italy – this disaffection with the political class, that career politicians seem to be looking after their own vested interests and not looking after the interests of ordinary voters.”

This is a bigger issue than One Nation. Huntley reports: “The general conversation from the community is that politicians seem like a kind of a club: they all know each other, they all went to university. They see them as highly educated, highly connected, an elite they have never been part of.” There’s anger across the board at the failure of government to solve problems. “They think, ‘There are these problems, these problems didn’t exist before, governments are responsible, I blame the government.’ So part of it is the easiest outlet for anger but also that kind of sense that politicians seem completely remote to them.”

Markus ran some figures for me from the Scanlon survey to show what those most angry with government are angry about. Gloom about the economy is clearly linked to dissatisfaction with government. But by far the most dramatic call for a shakeup of the system comes from those angriest about levels of immigration:

Other issues that fire up One Nation voters

Hanson’s people are not implacable conservatives. They aren’t hostile to unions and they believe – this figure in the AES is quite clear – that big business has too much power. Nor is One Nation preaching family values. They are not lining up against equal marriage. (In focus groups they say, ‘Why not let them get on with it?’) Hanson’s people are second only to the Greens in wanting marijuana decriminalised: 68% of Greens to 49% of One Nation. Not that they’ve given up on the War on Drugs. They loathe ice and fear it as a source of crime and violence. And Hanson’s people are absolutely of one mind on allowing the terminally ill to end their own lives with medical assistance: support in the party runs at 98%.On the other hand, Hanson’s people are particularly tough on crime. One of her causes back in the late 1990s was the right of parents to spank their children. She believes in the rod. But that’s only a start. Here’s the breakdown by party of those in 2016 calling for stiffer sentences for law breakers:

Greens 9%

Labor 24%

Liberal 30%

National 31%

One Nation 50%

And their faith in the gallows is complete. Twenty years ago, when the member for Oxley stormed into Canberra, there was a strong majority across the community for bringing back the noose for murder. That support has fallen, according to the AES, to 40%. But among One Nation voters, the passion for the death penalty is undiminished:

Greens 15%

Labor 40%

Liberal 42%

National 54%

One Nation 88%

Huntley is struck by the links between One Nation’s two agendas: law and order, and immigration. “Where I’ve worked with people who I know are One Nation voters or highly One Nation–empathetic, they will give absurd examples of their fears. I once met in South Australia this man who was very, very adamant on banning the burqa because he was concerned that large groups of women in their burqas would line up behind him at the ATM and steal his pin number. But the general way this plays out in groups is for someone to say, ‘Once upon a time you could leave your door open,’ or, ‘You could go to the pub and put your wallet next to your beer and go to the loo and you’d be surrounded by people just like you, people who would never even think to touch your wallet. But now you can’t do that.’ A discussion about asylum seekers and immigration will slip very quickly into that sort of talk. There’s a really intense nexus between law and order and immigration in that group.”

Yearning for the past

Which parties are Hanson voters deserting?

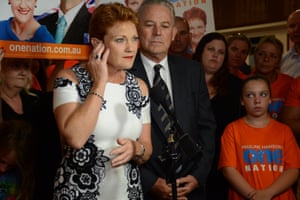

Rod Culleton and Pauline Hanson in the Senate chamber in Canberra in November. The controversy over her former colleague’s bankruptcy ‘hasn’t touched her’. Photograph: Mick Tsikas/AAP

That answer was straightforward the first time round: some Labor but mostly Coalition. Before the politicians drove Hanson out of parliament, the Coalition was in a world of pain. For every vote Kim Beazley lost, John Howard lost two. But the vote in 2016 was more complicated. Here’s the AES breakdown based on the previous choice of :Does Hanson have legs?

“As a protest vote I would have thought, yes,” says McAllister. “In the longer term it depends whether One Nation can basically transition from what is a charismatic party based on one individual through to a programmatic party that’s got a stable set of policy issues, and that’s the difficult part of it.” He watched that transformation with the Greens. It took time. “Labor voters generally were fed up with Labor so they voted Green. They only did it once and then they moved back to Labor. And then what we saw in the last three or four elections was this much greater retention of the Green vote. So it would take a long time for One Nation to transition into something more stable.”Those who see Hanson tapping into something murkier than mere disenchantment with politics fear One Nation will never be dealt with until the major parties find the courage to address the issue that haunts this country: race. Their understanding – it’s bipartisan – is that however they try to deal with the drift of votes to One Nation, they cannot afford to denounce Hanson as a racist. “We can only address this through dealing with their economic insecurities,” said Labor’s Kosmos Samaras. “If you say to someone, ‘Vote for us because that woman is racist,’ we’d be classified as elites. We’ll get killed electorally. If all we do is try to address the cultural issues, we’ll lose.” Of course, the big parties could try doing both: confront the racism and deal with the economic issues. But that isn’t happening. As Malcolm Turnbull and Shorten shift ground to try to win back One Nation’s vote, the R-word scarcely if ever passes their lips.

People listen to Hanson. It’s her gift. The only political asset she has is an unshakable belief out there that she speaks for real Australians as no politician can. Fighting her way back to parliament earned her fresh respect. Perseverance is admired in this country. We love a comeback. She’s been forgiven the blunders of the past to a remarkable degree. “She went too far back then,” they say in focus groups, by which they mean hounding Aboriginal people. Putting the boot into Muslims is seen, by contrast, as respectable work. A contradiction is beginning to stare her followers in the face. It doesn’t trouble them. She’s admired because she’s not a politician, while being credited on all sides with becoming more skilled at her work. “She’s a lot better now,” they say. “She’s learnt a lot, she knows what she’s doing.” And that is politics.

• Quarterly Essay 65: The White Queen by David Marr is out now

No comments:

Post a Comment