Military and climate experts, including a former chief of the defence

force have warned that Australia faces potential “disastrous

consequences” from climate change, including “revolving” natural

disasters and the forced migration of tens of millions of people across

the region, overwhelming security forces and government.

Former defence force chief Adm Chris Barrie, now adjunct professor at the strategic and defence studies centre at the Australian National University, said in a submission to a Senate inquiry that Australia’s ability to mitigate and respond to the impacts of climate change had been corrupted by political timidity: “Australia’s climate change credentials have suffered from a serious lack of political leadership”.

The inquiry into the security ramifications of climate change also heard from some of the country’s leading climate scientists, who warned the security threats posed by climate change had been underestimated, and complained Australia had been “walking away” from exactly the type of research that would help the country prepare.

Other experts, however, counselled against “alarmist” predictions and said the focus of climate change response should be on those people most acutely affected by it, rather than the security concerns of developed countries most able to respond.

Barrie said the security threat of climate change was comparable to that posed by nuclear war, and said the Australian continent would be most affected by changing climate.

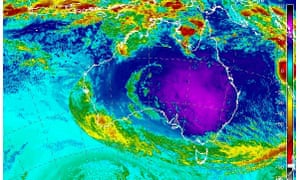

“We will suffer great effects from these changes, such as new weather patterns; droughts, sea-level rises and storm surges, because we have substantial urban infrastructure built on the coastal fringe; ravages of more intense and more frequent heatwaves and tropical revolving storms.”

But he said the existential impacts of climate change were likely to be first, and most severely, felt across Australia’s region, the Asia-Pacific rim, the most populous region in the world, and one that will be home to seven billion people by 2050.

Barrie posited a scenario in which the glaciers in the Tibetan Plateau and Himalayan-Hindu Kush ranges – which reliably deliver fresh water into China, the Mekong Delta, Myanmar, Bangladesh, India and Pakistan – would disappear.

“A serious shortage of fresh water brings famine; starving people are a very serious security problem. The question then becomes ‘what will happen if starving people on the rim of Asia are looking for a new home?’

“Historical evidence suggests that under such circumstances mass migration of these people will occur. It follows that several tens of millions of people might seek better fortunes in Australia and possibly New Zealand.

“Most other options for settlement in our region would already have high population densities. Our security forces, and all arms of government, would be overwhelmed in such a scenario.”

The Australian Defence Force has been examining the potential insecurities caused by climate change for a decade. Within Defence, there are serious concerns over the vulnerability of military bases to climate impacts, and the military’s reliance on fossil fuels.

But Barrie said political action lagged far behind and Australia’s hyper-politicised debate over climate had hampered decisive government action.

“Our current posture is a manifest failure of leadership,” he said.

Scientists at the ARC Centre for Climate Extremes, led by Andy Pitman from the University of New South Wales, said in their submission that climate scientists could help the country prepare for these sorts of threats but that investments in the required work was not occurring.

They noted many assessments of the threats to national security posed by climate change may be an underestimation, and called for a “high-level taskforce to examine risks associated with climate change and national security”.

“Most assessments linking climate change with climate risk have assumed changes are well described by the average,” they said, arguing this needed to be “urgently modified”.

They said that focusing on average temperature rise masks more serious changes that will occur in relation to extreme events and “compound events”.

“We do not know where or when extreme events will hit, which regions will become less vulnerable and which regions will suddenly emerge to be vulnerable,” they say.

They said those problems could be solved, but that Australia was not devoting enough research to the issue.

They also noted that while infrastructure and systems are often built to be resilient against isolated events – such as sea-level rise or a storm – that design often assumes they will happen in isolation, but if they occur together they could be “catastrophic”.

Again, the scientists said Australia was not focussing on the topic and noted that the US was examining compound events including the co-occurrence of droughts and heatwaves.

“Australia lags behind the US and some European countries in examining, assessing and responding to climate-change risks in terms of national security,” they said.

“Vulnerabilities associated with national security and climate change are already increasing and exist now. These are not ‘future issues’ that can be left for a decade before strategies are considered. The creation of a high-level taskforce to examine risks associated with climate change and national security is urgent and overdue.”

Jane McAdam, director of UNSW’s Kaldor centre for international refugee law told the inquiry climate change functioned as a “threat amplifier”, that magnified risk and exacerbated existing crises.

“Disasters become disasters on steroids: more frequent and more intense. Climate change is also a process. Slow-onset impacts such as sea-level rise or desertification take place over time, resulting in a gradual deterioration of living conditions that ultimately renders land uninhabitable.”

But she said the prospect of massive, sudden international migration was highly unlikely, and focused on the wrong people.

“Reasoned, empirically-grounded analysis has too often been overshadowed by alarmist and ill-informed assumptions about the numbers of people on the move, and the nature of that movement. As a result, the security analysis has been ‘flipped’ away from the needs of the most vulnerable communities to instead focus on the national security of developed states, premised on the flawed notion that they will be inundated by people fleeing the impacts of climate change.”

McAdam said most displacement and migration would occur within countries, not across national borders.

“Longer-term movement will generally be gradual rather sudden, and movement that is sudden (for instance, in the aftermath of a disaster) will often require temporary relief rather than permanent migration. There is scant evidence to justify claims that there will be mass outflows of people across international borders which will threaten international, regional or national security, or generate new risks of Islamist terrorism or fundamentalism.”

McAdam said internal displacement could generate low-level social tensions and potential conflict over key resources such as land, housing, food, water and employment.

The parliamentary inquiry has also heard climate change has already contributed to and worsened conflicts across the world, including in Mali, Yemen, and the Arab Spring and civil war in Syria from 2011.

The International Committee of the Red Cross said the destruction of the natural environment or access to scarce resources was often used as a weapon of war.

“In armed conflict, the natural resources on which people rely are often attacked in contravention of IHL [international humanitarian law] provisions. This can take the form of theft or killing of livestock, theft of land, drainage or poisoning of water resources, destruction of places of trade and livelihood. Removing the basis of communities’ resilience and capacity to adapt to changing weather conditions imperils their survival and contributes to displacement and poverty.”

Former defence force chief Adm Chris Barrie, now adjunct professor at the strategic and defence studies centre at the Australian National University, said in a submission to a Senate inquiry that Australia’s ability to mitigate and respond to the impacts of climate change had been corrupted by political timidity: “Australia’s climate change credentials have suffered from a serious lack of political leadership”.

The inquiry into the security ramifications of climate change also heard from some of the country’s leading climate scientists, who warned the security threats posed by climate change had been underestimated, and complained Australia had been “walking away” from exactly the type of research that would help the country prepare.

Other experts, however, counselled against “alarmist” predictions and said the focus of climate change response should be on those people most acutely affected by it, rather than the security concerns of developed countries most able to respond.

Barrie said the security threat of climate change was comparable to that posed by nuclear war, and said the Australian continent would be most affected by changing climate.

“We will suffer great effects from these changes, such as new weather patterns; droughts, sea-level rises and storm surges, because we have substantial urban infrastructure built on the coastal fringe; ravages of more intense and more frequent heatwaves and tropical revolving storms.”

But he said the existential impacts of climate change were likely to be first, and most severely, felt across Australia’s region, the Asia-Pacific rim, the most populous region in the world, and one that will be home to seven billion people by 2050.

Barrie posited a scenario in which the glaciers in the Tibetan Plateau and Himalayan-Hindu Kush ranges – which reliably deliver fresh water into China, the Mekong Delta, Myanmar, Bangladesh, India and Pakistan – would disappear.

“A serious shortage of fresh water brings famine; starving people are a very serious security problem. The question then becomes ‘what will happen if starving people on the rim of Asia are looking for a new home?’

“Historical evidence suggests that under such circumstances mass migration of these people will occur. It follows that several tens of millions of people might seek better fortunes in Australia and possibly New Zealand.

“Most other options for settlement in our region would already have high population densities. Our security forces, and all arms of government, would be overwhelmed in such a scenario.”

The Australian Defence Force has been examining the potential insecurities caused by climate change for a decade. Within Defence, there are serious concerns over the vulnerability of military bases to climate impacts, and the military’s reliance on fossil fuels.

But Barrie said political action lagged far behind and Australia’s hyper-politicised debate over climate had hampered decisive government action.

“Our current posture is a manifest failure of leadership,” he said.

Scientists at the ARC Centre for Climate Extremes, led by Andy Pitman from the University of New South Wales, said in their submission that climate scientists could help the country prepare for these sorts of threats but that investments in the required work was not occurring.

They noted many assessments of the threats to national security posed by climate change may be an underestimation, and called for a “high-level taskforce to examine risks associated with climate change and national security”.

“Most assessments linking climate change with climate risk have assumed changes are well described by the average,” they said, arguing this needed to be “urgently modified”.

They said that focusing on average temperature rise masks more serious changes that will occur in relation to extreme events and “compound events”.

“We do not know where or when extreme events will hit, which regions will become less vulnerable and which regions will suddenly emerge to be vulnerable,” they say.

They said those problems could be solved, but that Australia was not devoting enough research to the issue.

They also noted that while infrastructure and systems are often built to be resilient against isolated events – such as sea-level rise or a storm – that design often assumes they will happen in isolation, but if they occur together they could be “catastrophic”.

Again, the scientists said Australia was not focussing on the topic and noted that the US was examining compound events including the co-occurrence of droughts and heatwaves.

“Australia lags behind the US and some European countries in examining, assessing and responding to climate-change risks in terms of national security,” they said.

“Vulnerabilities associated with national security and climate change are already increasing and exist now. These are not ‘future issues’ that can be left for a decade before strategies are considered. The creation of a high-level taskforce to examine risks associated with climate change and national security is urgent and overdue.”

Jane McAdam, director of UNSW’s Kaldor centre for international refugee law told the inquiry climate change functioned as a “threat amplifier”, that magnified risk and exacerbated existing crises.

“Disasters become disasters on steroids: more frequent and more intense. Climate change is also a process. Slow-onset impacts such as sea-level rise or desertification take place over time, resulting in a gradual deterioration of living conditions that ultimately renders land uninhabitable.”

But she said the prospect of massive, sudden international migration was highly unlikely, and focused on the wrong people.

“Reasoned, empirically-grounded analysis has too often been overshadowed by alarmist and ill-informed assumptions about the numbers of people on the move, and the nature of that movement. As a result, the security analysis has been ‘flipped’ away from the needs of the most vulnerable communities to instead focus on the national security of developed states, premised on the flawed notion that they will be inundated by people fleeing the impacts of climate change.”

McAdam said most displacement and migration would occur within countries, not across national borders.

“Longer-term movement will generally be gradual rather sudden, and movement that is sudden (for instance, in the aftermath of a disaster) will often require temporary relief rather than permanent migration. There is scant evidence to justify claims that there will be mass outflows of people across international borders which will threaten international, regional or national security, or generate new risks of Islamist terrorism or fundamentalism.”

McAdam said internal displacement could generate low-level social tensions and potential conflict over key resources such as land, housing, food, water and employment.

The parliamentary inquiry has also heard climate change has already contributed to and worsened conflicts across the world, including in Mali, Yemen, and the Arab Spring and civil war in Syria from 2011.

The International Committee of the Red Cross said the destruction of the natural environment or access to scarce resources was often used as a weapon of war.

“In armed conflict, the natural resources on which people rely are often attacked in contravention of IHL [international humanitarian law] provisions. This can take the form of theft or killing of livestock, theft of land, drainage or poisoning of water resources, destruction of places of trade and livelihood. Removing the basis of communities’ resilience and capacity to adapt to changing weather conditions imperils their survival and contributes to displacement and poverty.”

No comments:

Post a Comment