Controversial scheme which quarantines up to 80% of a welfare recipient’s payments will become permanent across four trial sites

Last modified on Thu 15 Oct 2020 03.32 AEDT

Welfare recipients on the cashless debit card say they feel a sense of “hopelessness” after the federal government announced plans to make the scheme permanent across four trial sites.

The decision in this month’s federal budget comes as the most recent figures show a provision to allow cardholders to exit the scheme has only approved one in four applications.

It means most of the 12,000 welfare recipients living in Ceduna, South Australia, the East Kimberley and the Goldfields areas of Western Australia, and Hervey Bay and Bundaberg in Queensland are likely to be stuck on the card until they move off benefits.

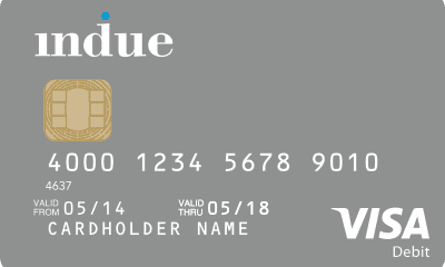

The controversial scheme quarantines up to 80% of a welfare recipient’s payments on to a card operated by Indue, which cannot be used on products such as alcohol or gambling.

Research has questioned the card’s utility, but the government insists it’s working to reduce social harms in areas where there are high numbers of welfare recipients.

Bundaberg resident Emilie Randell, 28, was placed on the card in November 2019 after she finished full-time study and moved on to jobseeker payment.

Randell, who noted she also works casually in hospitality, said before the card she’d “never been late on my rent, whether as a worker or a student”.

“I’ve lost count of the amount of time Indue has blocked my rent payments,” she said. “Now I pay that out of my wages.”

Under legislation described as “toxic” by Greens senator Rachel Siewert and introduced to parliament last week, the card would become “ongoing” in the current trial sites.

The trials are currently due to expire in December, but the new bill would mean parliament would no longer need to continually approve the card’s presence in these areas.

It will also move about 25,000 people in the Northern Territory and Cape York on to the program, a decision strongly criticised by Aboriginal Peak Organisations Northern Territory. Welfare recipients in the NT and Cape York are already on the “basics card”, which was introduced 12 years ago during the Howard government’s NT intervention.

Randell said the decision to make the card permanent where she lives was difficult to accept.

“It is hard to put into words, I guess hopelessness is the best word to describe it,” she said.

“I was putting everything into them ending the trial in December. I’m really frightened for what it means for the future.”

The government has argued it is continually improving the card, which it now describes as a tool to improve financial literacy among welfare recipients.

It is developing a “product level blocking” feature that aims to ensure cardholders can use their card at any shop or venue.

"The back of the card is bright purple, so every time I use it I feel like the cashier knows I’m unemployed, even though I do work"

Currently, the government blocks “entire merchants which sell restricted items”, but the change would allow products to be blocked during a transaction.

A spokeswoman for the social services minister, Anne Ruston, said the government was “committed to making sure that it is no different to that provided to any other banking customers”.

While the government has moved to remove the “Indue” name from the cards and make them “less identifiable”, Randell said her card contained the company’s logo.

“The back of the card is bright purple, so every time I use it I feel like the cashier knows I’m unemployed, even though I do work,” she said.

Earlier in the year, Guardian Australia reported that a new process allowing participants to “exit” the program had been plagued by long delays.

New government figures to 4 September show that of the 1,280 applications to exit the card, only 311 (or 24%) have been approved.

One card holder who moved from Hervey Bay to Brunswick, a small town east of Bunbury, WA, is among those to have had her application denied. The card’s rules mean a person remains on the program even if they move away.

The 24-year-old mother of two, who did not want to be named, said local businesses, including the IGA, some petrol stations and op-shops did not accept her card.

Few people know what the card is in Brunswick and some assume she’s been “put on it through child services”.

She said recent issues had included being forced to take out a loan to buy a second-hand couch for her new home and difficulties paying for her five-year-old’s school uniforms and book club.

“I’m trying to establish a home,” the woman said. “I’m trying to rebuild myself ... I was in a DV relationship which I managed to escape, that was another reason I left [Hervey Bay]. We came here with nothing.”

The card has won the support of several Coalition MPs, including Rowan Ramsey, who represents Ceduna, and Keith Pitt, who advocated for the card to be introduced in his Queensland electorate of Hinkler.

The mother-of-two said she understood what the government was trying to do. “I understand where they’re coming from, growing up in a high drug and alcohol area as a child and having been a victim of parents not doing the right thing,” she said.

“But they don’t need to punish everyone. The fundamentals don’t work and it’s not targeting the right people. When I have to call these people [to complain about declined transactions] and I have anxiety, it’s quite upsetting and it’s stressful.

“It’s hard to have a 40-minute conversation ... while I’ve got a screaming toddler in the background, when it should be as easy as logging on to the internet and paying your rent.”

Ruston’s spokeswoman said the government was “confident that welfare quarantining measures … have a positive impact on participants and the broader community”.

“The cashless debit card is the most sophisticated of these measures and is becoming one of the most advanced bank cards in Australia, supporting welfare recipients to improve their budgeting skills and reducing social harm,” she said.

No comments:

Post a Comment