Extract from The Guardian

Newly released letters written by the former governor general show he regarded his forced resignation under the Fraser government as the ultimate betrayal.

Last modified on Mon 26 Oct 2020 03.32 AEDT

In the cryptic taxonomy of archives, the relationship between Sir John Kerr and the Queen stretches beyond the palace letters and into obscure files scattered throughout the National Archives of Australia and elsewhere. The most surprising of these is a new set of letters between Kerr and Sir Martin Charteris in the National Archives of Australia.

From all these archives – in personal letters, Kerr’s rambling handwritten notes, and his unguarded personal reflections – a common theme emerges: the involvement of the palace in every step Kerr took, and every decision he made, regarding the dismissal of Gough Whitlam and its gathering aftermath, including even his own resignation. It is impossible to separate Kerr’s decisions from his intractable view of his “duty” to the monarch and the monarchy, presented to him so clearly in the months before the dismissal by Queen’s private secretary, the unctuous Charteris.

Charteris had worked that sense of duty perfectly, most notably in his reassurance to Kerr that whatever decision he was to make, it could only do the monarchy good. Kerr’s decisions were in this sense entirely bounded by considerations of his view of the interests of the Queen and what was best for the monarchy. There was, quite simply, no decision that Kerr would make without what he saw as the imprimatur of the palace. How could it have been otherwise? For Kerr, his duty defined his decisions.

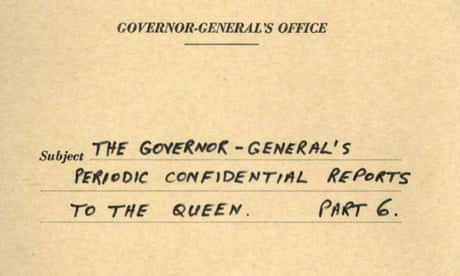

Soon after the release of the palace letters, several previously unpublished letters from one of those obscure files were unexpectedly and quietly released by the archives, nine years after I first requested it. This file, carrying the incongruous title “Correspondence between the prime minister and the governor-general on the governor-general’s resignation”, contained several letters between Kerr and Charteris that were not included with the palace letters released by the archives with such fanfare following the high court decision. Apart from anything else, this raises the significant question of how many more of these historic letters lie elsewhere in the archives, imperfectly labelled and unseen, which ought to form part of the broader palace letters collection.

The newly released documents consist of several anguished letters, drafted and redrafted by Kerr to Charteris in 1977 in the months before his reluctant resignation, and a single letter from Charteris in reply. They tell a poignant story of personal decline. These letters provide a snapshot of the distressed end of Kerr’s term as governor general, of his deteriorating relationship with the palace, and of his dramatic turn against Malcolm Fraser, as those who had encouraged and cajoled him in the months before the dismissal began to move against him.

In the early months after the dismissal, in the afterglow of the successful revival of the reserve powers of the Crown, Kerr describes the view from the government, and “encouraged” by the palace, that he “should, indeed, must stay”. It is essential that he “avoid appearing to concede error” in any way about his dismissal of Whitlam. As Kerr navigates the shifting fortunes in his position, a detailed handwritten note prepared by him in April 1976 reveals the role of “the palace”, Charteris, and Prince Charles, as part of a select group of informal advisers with whom he discussed his future as governor general. Kerr sought advice from Prince Charles, the palace, Sir Robert Menzies, Sir Anthony Mason, prime minister Fraser, and Sir Garfield Barwick. They had all urged him to remain as governor general because, “(1) what I did was the right thing to do and (2) resignation … would leave the impression that I regretted what I did”.

Despite

the private professions of support and encouragement, as the months

pass and the protests against him continue, Kerr perceives a change.

Privately, he writes of his growing fear that “the Government, or some

of its members, may get tired of defending me … and encourage me to go”.

And if they did, Kerr would not go easily. He would not even consider

resigning without a new position to go to. In a sign of his faltering

judgment as his concern for his position grows, Kerr imagines that

Fraser might consider appointing him as Australia’s high commissioner to

the United Kingdom. “London might be the best place to spend a few

years,” he muses. It is hard to understand how Kerr could have

entertained the idea that after such intense political controversy, he

could be appointed to a plum diplomatic role by the government he had

installed in office just months earlier.

In an extraordinary letter to Charteris in late 1976, when his relationship with Fraser is already splintering, Kerr raises the possible use of the reserve powers against the government. Kerr writes that Fraser faces several options for the next election, including a half-Senate election, or an early election for the House of Representatives. He sets out the possibility, raised by some commentators, that “because of my view that the Governor-General has a real discretion”, he ought to consider whether there is a case for invoking the reserve powers to deny Fraser such an early election. Kerr reminds Charteris, with the air of one with a shared understanding, that these powers exist and are available to him.

Charteris’s response is emphatic, and quite unlike his benign insistence on the existence of the reserve powers, and even of their possible beneficial use, just the previous year. “I hope that this possibility will not arise, both for your own sake and also I think for the sake of the Crown,” he writes, firmly closing off that discussion.

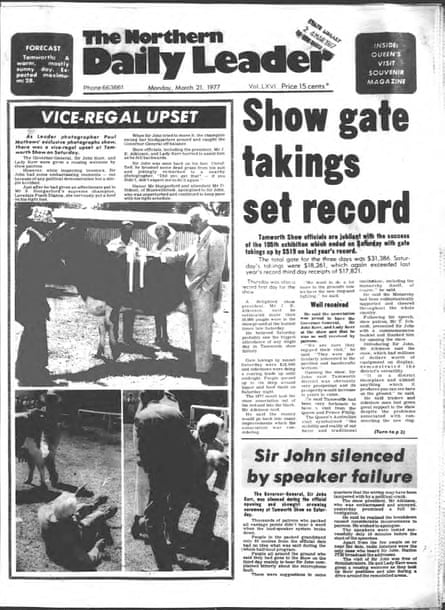

By 1977, Kerr’s behaviour at public events was also becoming a liability. That was the year he landed face-down in the mud at the Tamworth Show as he attempted to place the winning medallion around the prized cow “Lovedale Posh”, all of it captured by a waiting photographer. The front-page images of the governor general pinioned under the cow’s hoof won a Walkley award. There was a memorable repeat performance at the Melbourne Cup later that year when Kerr, in an ill-fitting top hat and tails, struggled to remain upright as he awarded the cup to the owners of the winning horse. It was a sad sight of a public decline (now a much-watched YouTube clip called, “the Governor-General drunk at the Melbourne Cup”).

Kerr’s inadvertent burning of the carpet at Victoria’s Government House during a short visit, when he tripped over the heater in the middle of the night and woke to find the carpet smouldering, no doubt also caused ripples of anxiety in vice-regal circles. And so, it is hardly surprising that by 1977 the Queen had joined the list of those who wished the governor general to make an early retirement. In little more than a year he had gone from saving the Queen from embarrassment to being the embodiment of that embarrassment. Kerr’s greatest fear under Whitlam, his removal from office, would now ensue under Malcolm Fraser.

Kerr’s forced resignation was, to him, the ultimate betrayal by Fraser, whose political fortunes during the 1975 crisis his unprecedented actions had assured. The newly released cache of letters and drafts to Charteris is a raw display of devastation. In an extraordinarily indiscreet draft letter, Kerr writes that Fraser had never given him the support that “I have been entitled to have”, and that now, “victory achieved”, Fraser is “happy for me to go”. The well-honed vituperation that Kerr once deployed against Whitlam he turns towards Fraser, “a stern, distant, arrogant man determined to rule completely and not able to relax in conversation with me as Mr Whitlam was able to do”. Whitlam is now, apparently, not so bad after all.

This is an edited extract from The Palace Letters: The Queen, the governor-general, and the plot to dismiss Gough Whitlam by Jenny Hocking, out 27 October (Scribe, $32.99)

No comments:

Post a Comment