Extract from The Guardian

Katharine Murphy on politics Australian politics

Whatever happened to sanctions for poor judgment, a ritualised apology or even a modicum of embarrassment?

Last modified on Sat 13 Feb 2021 06.02 AEDT

With a national Covid-19 vaccination rollout imminent, you’d think Greg Hunt might have better things to do than trying to shore up Kevin Andrews in a Victorian preselection, or branding the ABC broadcaster Michael Rowland an undeclared leftist when he faced a persistent line of questioning he didn’t like.

The purpose of revisiting Hunt’s egregiousness is not to be distracted by the theatrics of the health minister’s staged fight with Rowland in the middle of this week.

I want to track back to the substantive question Hunt was asked. Rowland’s question on Wednesday morning was prompted by Hunt’s decision to attach the Liberal party logo to a Twitter post trumpeting an extra 10m doses of the Pfizer Covid-19 vaccine.

The Liberal party wasn’t funding these vaccines, Australian taxpayers were, so why was this a party political announcement?

The health minister counselled Rowland (“with great respect”) that he was “elected under that [Liberal party] banner” and was a “very proud member of that party with a great heritage and tradition in Australia”.

Stirring stuff obviously. Makes the heart swell.

But entirely irrelevant.

Hunt attacked Rowland’s professionalism because the health minister didn’t have a compelling answer to the question that would have passed any sort of pub test.

There really is no good answer to that question, apart from “I am a goose, Michael” – so attack was seen as the best form of defence.

The health minister blustered that he saw no problem with attaching a Liberal party logo to a government announcement in the middle of a pandemic costing lives and threatening livelihoods.

This was within the rules. “Entirely within the rules.”

It was a similar story in Melbourne on Friday when Scott Morrison was on 3AW with Neil Mitchell.

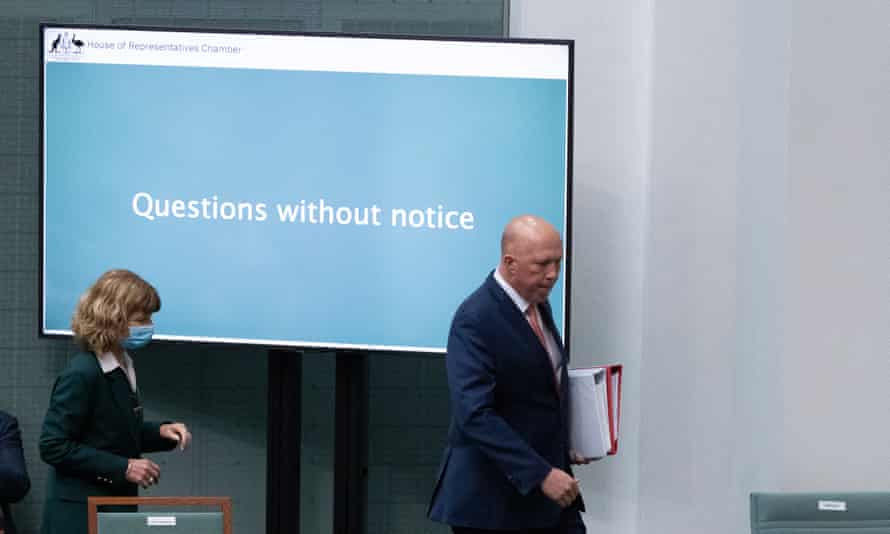

Morrison was asked about a story unearthed by the ABC earlier in the week about Peter Dutton asking his department to fast-track a grant proposal from the National Retailers Association weeks after the industry body made a political donation to support the home affairs minister. Labor has subsequently referred Dutton’s management of community safety grants to the Australian National Audit Office.

Given the whole sports grants saga, Mitchell wondered whether the prime minister might look into this. Morrison thought not. “There’s nothing in front of me that says he’s done anything outside the rules”. When Mitchell pressed, Morrison blocked with a mildly mangled locution: “It’s an allegation that hasn’t been backed up by any breaches of any rules that have been alleged”.

Couple of things.

It’s not entirely clear how Morrison knows no rules have been breached given he’s the busiest man in the country, and his self-nominated threshold for further investigation is whether or not something appears “in front of me” (which seems a little arbitrary).

But beyond that basic evidentiary point, there’s a bigger problem, and it’s this.

Too few people in public life seem to want to ask themselves more fundamental questions – whose interests do “the rules” serve, or do “the rules” stink?

Just while we are on “the rules” exoneration, I need to make the point that, more often than not, these are their rules – which is a subtle but important distinction.

“The rules” sounds like immutable propositions enunciated by a minor deity or an independent eminence.

But the fact is parliamentarians make the laws, and write the rules. So not “the rules”. Their rules. Which perhaps explains the distinct lack of curiosity about how their rules could be improved (or, God forbid, policed by an independent agency with a serious remit).

The disturbing thing about all this is not so much that some professionals within an ecosystem create structures that serve their short-term interests – a cynic would say that’s politics.

The disturbing thing, from my vantage point, is how brazen various protagonists are becoming about their behaviour. Once there would be actual sanctions for poor judgment (or worse) – or at least a modicum of embarrassment, or a ritualised apology.

Now, many of these characters act like they are teflon-coated. There is a swagger to the whole self-serving complex, which is a relatively new development, and a deeply uncomfortable one.

Some recent examples. The New South Wales deputy premier, John Barilaro, appearing before a parliamentary inquiry into the state government’s alleged pork barrelling of council grants on Monday, did not take a backward step.

“When you think about it, every single election that every party goes to – we make commitments,” he said. “You want to call that pork barrelling, you want to call that buying votes – it’s what the elections are for”.

Barilaro argued that what others call “pork barrelling” was actually an “investment” in the regions. “It’s a name that I’ve never distanced myself from because I’m actually proud of ... what it represents,” he said.

Last year, the premier, Gladys Berejiklian, also copped to pork barrelling but reasoned there was nothing illegal about it. “It’s not something the community likes ... but it’s an accusation I will wear,” the premier said. “It’s not unique to our government. It’s not an illegal practice. Unfortunately it does happen from time to time by every government”.

Well, yes, unfortunately it does, particularly in cases where there is little apparent desire to do otherwise, and a natural tendency towards self-exoneration.

On Friday, we had the former federal sport minister Bridget McKenzie appearing before the Senate inquiry into the sports grants fiasco. McKenzie of course did face consequences after the audit office savaged the Coalition’s management of the program. She lost her job.

During her appearance on Friday, McKenzie knew a bunch of things. She knew sports grants was a good program, which she’d managed tremendously, whatever you might read in a “somewhat middle of the road” assessment by the ANAO, or hear from her political opponents. (Just for the record, the ANAO found the grants were skewed towards marginal seats).

McKenzie knew she was the responsible minister who made the decisions about grant allocations, not Scott Morrison. She didn’t know who altered a list of successful grants on the day federal parliament was prorogued for the 2019 election – but she assumed it was a member of her staff, but she wasn’t sure which one, and she hadn’t asked.

McKenzie also knew she prepared for a meeting with Morrison in November 2018 to discuss expanding the sports grants program, but she didn’t know what was in a talking points brief prepared by her adviser for that conversation. The ANAO has said previously that briefing material included spreadsheets demonstrating how many more projects in marginal and targeted seats could be funded by expanding the program from $30m to $100m.

Even though McKenzie said on Friday she was “not at all aware” of what was in that document, she was very confident the contents had not been canvassed with Morrison. In other words, the defence was effectively: I don’t know what was in that brief, but I know we didn’t talk about it (insert head scratching emoji).

And so it went, round and round, until the hearing erupted in acrimony and the Liberal senator Eric Abetz noted “we’ve all got planes to catch”.

Meanwhile, we are stuck with “the rules” – and the Morrison government continues to drag its heels on establishing a national integrity commission.

No comments:

Post a Comment