Extract from The Guardian

A ‘confronting and sobering’ report details degradation of coral reefs, outback deserts, tropical savanna, Murray-Darling waterways, mangroves and forests

Last modified on Fri 26 Feb 2021 06.46 AEDT

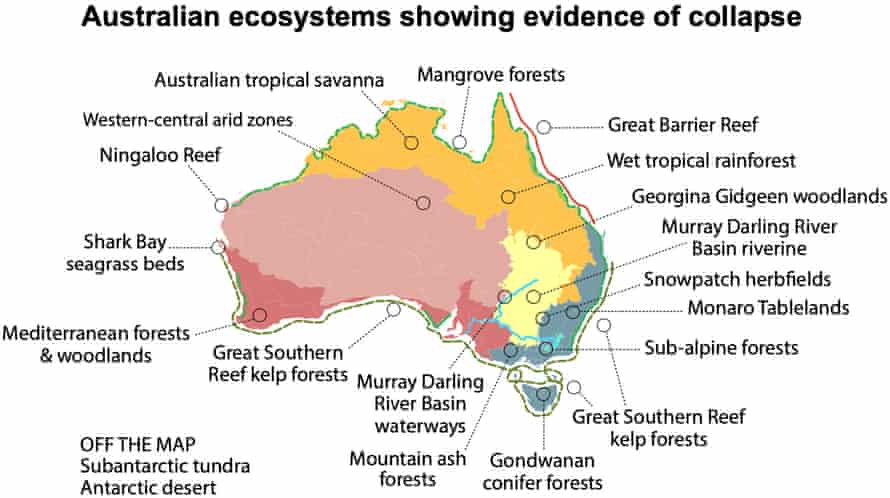

Leading scientists working across Australia and Antarctica have described 19 ecosystems that are collapsing due to the impact of humans and warned urgent action is required to prevent their complete loss.

A groundbreaking report – the result of work by 38 scientists from 29 universities and government agencies – details the degradation of coral reefs, arid outback deserts, tropical savanna, the waterways of the Murray-Darling Basin, mangroves in the Gulf of Carpentaria, and forests stretching from the rainforests of the far north to Gondwana-era conifers in Tasmania.

The list of damaged ecosystems extends beyond the continent to include subantarctic tundra of world heritage-listed Macquarie Island and moss beds in the east Antarctic.

The study’s lead author, Dr Dana Bergstrom from the Australian Antarctic Division, said 19 out of 20 ecosystems examined were experiencing potentially irreversible environmental changes, including the loss of species and the ability to perform important functions such as pollination.

Bergstrom said the collapses were a result of the ecosystems experiencing multiple pressures simultaneously. Some, such as rising average temperatures due to the climate crisis, habitat loss and invasive species, are chronic. Others are acute short-term events, many of them exacerbated by global heating. They include heatwaves, fires and storms.

While the report paints a dire picture, Bergstrom said a key message was that action now could still make a difference.

“None of the 19 ecosystems has yet collapsed across its entire range, but for all case studies there is documented evidence of ecosystem collapse in some areas,” she said.

“Urgent action will be essential to prevent the loss of any of these ecosystems in their entirety.”

Previous in-depth studies – including the government’s state of the environment report and last year’s review of the national environment laws by the former competition watchdog head Graeme Samuel – have found Australia’s natural heritage is in a perilous and worsening state, but they have mostly not considered in-depth what is happening within ecosystems.

The new report, which is published in the journal Global Change Biology, involved trawling peer-reviewed scientific papers and other reports to collect empirical data of the health of ecosystems, and assessing the results against criteria to determine whether they had changed state.

All but one of the ecosystems was found to have a low likelihood of recovery and to be heading towards permanent collapse. The exception was the subtropical rainforests of coastal New South Wales, which have been damaged to a lesser extent.

Among the examples in the report are the alpine ash forests of Victoria, which were found to be so frequently hit by fire that they often did not have enough time to produce seeds. In response, scientists had begun planting hybrid species that may cope better in the changed conditions.

Prof Euan Ritchie, from Deakin University and one of the authors, said the report was arguably the most comprehensive analysis of Australia’s environment to date. “It is confronting and sobering,” he said.

He cited the example of the tropical savannas across northern Australia that had been degraded by frequent fires, overgrazing by livestock and feral animals and, increasingly, extreme weather events.

It meant once-widespread native species such as the brush-tailed rabbit-rat were now rare and found in the few places where good habitat remained. “Improving fire management [and] feral animal and weed control are easily achievable steps we can take to protect this ecosystem and its remarkable and unique species, which also have significant cultural and economic value,” he said.

Bergstrom said while the idea that nature would take its own course was still pervasive, it was now time “to actually interfere with nature because we’re losing too much if we don’t”.

She said it was important to acknowledge work to bolster the environment was happening – from landcare and conservation groups and through actions supported by federal and state governments, including Indigenous ranger programs – but the report showed a more urgent and targeted response was needed.

“People talk about climate change as something in the future. Climate change is here and collapse is coming,” she told Guardian Australia. “But we have the ability and we have the skills. We just need the willpower to make it happen.

“Protecting these iconic ecosystems is not just for the animals and plants that live there. Our economic livelihoods, and ultimately our survival, are intimately connected to the natural world.”

The ecosystem report has been published as the government is facing criticism for not immediately acting on many of the recommendations made in Samuel’s review of the national environment laws.

Samuel found the laws were failing, and the government would be accepting the decline of celebrated environmental landmarks and the extinction of threatened animals, plants and ecosystems unless it embraced fundamental reform.

The government has introduced legislation for new national environmental standards as Samuel suggested, but has been accused of merely mimicking the existing laws and doing nothing to strengthen protection. Its proposed “assurance commissioner” to oversee the laws would not have the power to investigate decisions about specific developments.

While official data suggests Australia has the highest rate of mammal extinction over the past 200 years, the government has largely rebuffed calls for increased spending on the environment.

Funding for environment department and related programs were cut by more than a third after the Coalition was elected in 2013. Some was restored last year, much of it directed to “congestion busting” – increasing the pace at which development proposals were assessed.

An alliance of more than 70 conservation, farming and land management organisations last year pitched a $4bn plan to help repair the natural environment, saying it could create 53,000 jobs and boost regional economies in the wake of Covid-19. The government expressed interest in the report, but has not adopted its suggestions.

No comments:

Post a Comment