Extract from The Guardian

Researchers fear increasing energy in these eddies could affect ability of Southern Ocean to absorb C02.

Last modified on Fri 23 Apr 2021 01.01 AEST

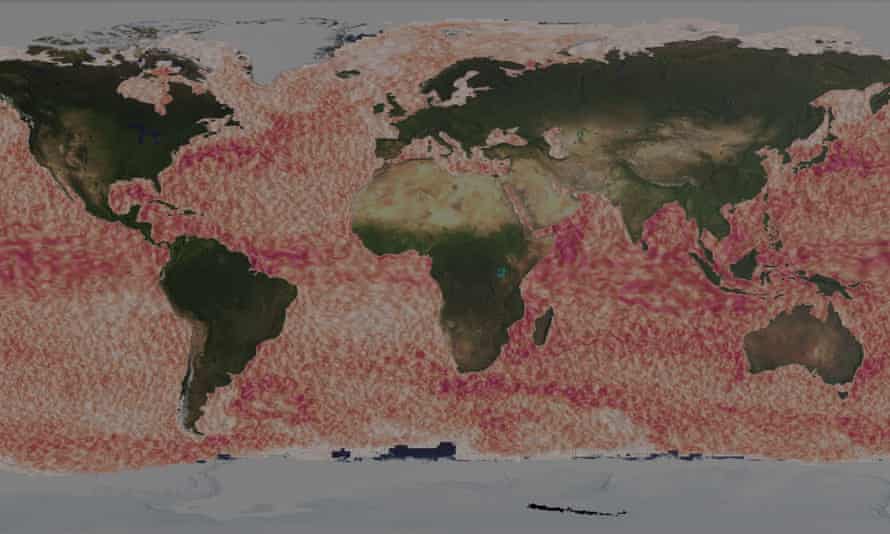

Swirling and meandering ocean currents that help shape the world’s climate have gone through a “global-scale reorganisation” over the past three decades, according to new research.

The amount of energy in these ocean currents, which can be from 10km to 100km across and are known as eddies, has increased, having as yet unknown affects on the ocean’s ability to lock-away carbon dioxide and heat from fossil fuel burning.

One expert said the changes described in the research could affect the ability of the Southern Ocean, one of the world’s biggest natural carbon stores, to absorb CO2.

The study, published in the journal Nature Climate Change, analysed the temperature and height of the ocean with the help of data from altimeters on satellites from 1993 until 2020.

Like clouds and storms in the atmosphere, eddies are like weather events in the oceans happening from the surface down to a depth of several hundreds metres. The research found that eddies were intensifying in places where they are known to be most active.

As well as detecting changes in the Southern Ocean, the research also found changes in the southern Atlantic, the east Australian current.

They found a significant increase in eddy strength over the Southern Ocean, as well as significant changes in their activity over the boundary currents – the intense flows of water along the boundaries of the major ocean basins, such as the Gulf Stream and the East Australian Current.

Lead researcher Josué Martínez Moreno, of the ARC Centre of Excellence for Climate Extremes and Australian National University, said the eddies were constantly merging and detaching from more permanent ocean currents.

The eddies played a “profound role” in moving heat, carbon and nutrients through the ocean and regulating the climate at regional and global scales, the research said.

Martínez Moreno said the research had revealed “a global-scale reorganisation of the ocean’s energy over the past three decades”.

The paper did not attempt to attribute the changes to human activity, but Martínez Moreno said they could have far-reaching effects on the world’s climate, and also on fisheries.

Getting a better understanding of the changes in ocean eddies could also improve climate change projections, he said.

As well as absorbing about 90% of global heating since the 1970s, the ocean has pulled in about 40% of the extra carbon dioxide emitted into the atmosphere, mainly from fossil fuel burning, since the start of the Industrial Revolution.

A co-author of the study, Prof Matthew England, of the Climate Change Research centre at the University of New South Wales, said: “We know these eddies play an important role in the climate, but how this intensification might change a given weather pattern is hard to say.

“To see it changing at this scale to me is confronting,” he said. “To see these changes shows how much we are perturbing the system. There will be impacts on our climate and ecosystems that we will have to explore now.”

Solving the puzzle of how these ocean eddies were changing was “one of the last frontiers” in understanding how climate change could be affecting the ocean, he said.

Dr Janet Sprintall, an oceanographer at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in California, who was not involved in the research, said the findings were “a great step forward.”

She said: “The world’s oceans soak up most of the carbon dioxide that humans dump into the atmosphere. The Southern Ocean in particular absorbs about 40% of the entire ocean uptake and much of that uptake is achieved by ocean eddies.”

Any change in the ocean eddies in the Southern Ocean, she said, can “potentially impact the carbon sink and the ability to uptake carbon that we might continue to emit in the future”.

“This could have devastating effects on global society.”

The research came after the United Nations released its second assessment on the world’s oceans on Wednesday, cataloguing a swathe of impacts on what UN secretary general António Guterres said was the planet’s “life support system”.

Sea levels were rising, coasts were eroding, waters were heating and acidifying and the number of deoxygenated “dead zones” was rising.

Marine litter was present in all marine habitats, the report said, and overfishing was costing societies billions. About 90% of mangrove, seagrass and marsh plant species were threatened with extinction, the report said.

The report said there had been progress in protecting more marine areas, but there were still many scientific knowledge gaps to be filled.

No comments:

Post a Comment