Extract from The Guardian

People in Britain with little chance of dying are being vaccinated despite continued suffering in the developing world.

Last modified on Tue 27 Apr 2021 03.03 AEST

The idea that nobody is protected until everyone’s protected has become something of a pandemic cliche lately.

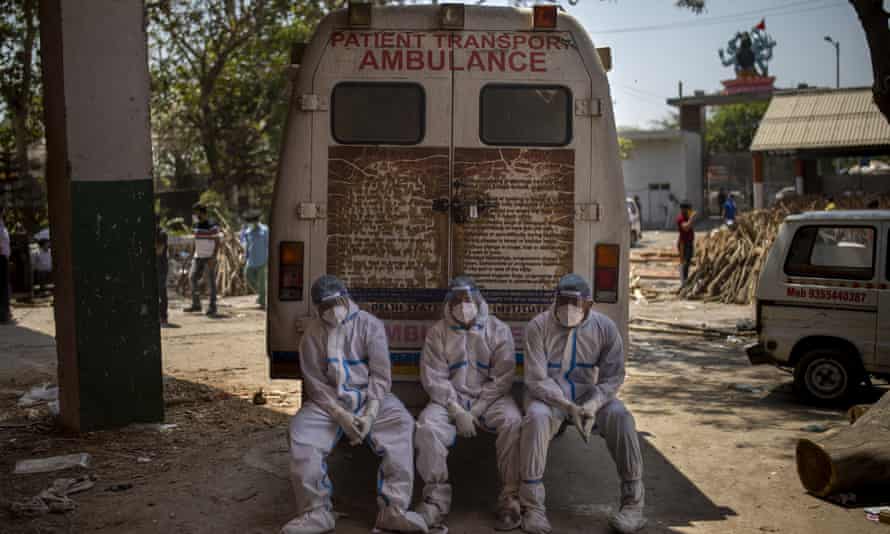

Yet that doesn’t make it any less true, clinically or morally. As long as the virus is rife in any country, it could always mutate and spread again. What is only now becoming obvious, however, is that as long as others are experiencing horrors on the scale of India, consciences everywhere will be troubled. The harrowing scenes unfolding nightly on our television screens are what Britain feared but ultimately did not have to suffer: hospitals running out of oxygen, people dying in the street for lack of a bed, families forced to bury the dead in their gardens as crematoriums were overwhelmed. India’s tragedy is a stark reminder of Britain’s own relative good fortune, hard as this year has been for many. But to be lucky is a morally queasy, guilty thing.

The success of Britain’s vaccination programme, with half the country having had at least one shot and the NHS hoping to start calling up thirtysomethings soon, remains an amazingly heroic effort. But it does not sit right that India, one of the world’s leading manufacturers of vaccines, should have entered the gates of Covid hell with fewer than 10% of its population jabbed. For the many Britons with family ties to India, these are deeply anxious times.

At the weekend, it emerged that a Downing Street aide had tested positive for Covid after travelling to India, prompting alarmist headlines about how he might have spread a new variant through Whitehall. But arguably the more troubling aspect was that he was reportedly sent out to try to get more Indian-manufactured doses of vaccine for Britain, at a time when the Indian government – for reasons now all too distressingly obvious – was seeking to hold back many of the doses it was previously exporting in their millions, many destined for developing countries. The British mission apparently left empty-handed, but one is left wondering uncomfortably if it was even right to try. How can it not ultimately backfire on the richest countries if they’re seen to be snaffling up more than their share of resources yet again?

In a sense, this tangled web of global guilt and resentment is nothing new. That some countries have ordered more vaccines than they can use, while others served by the Covax initiative to procure vaccines for developing nations may have to wait until 2024 to reach mass immunisation, is no more or less fair than the way British households throw away an estimated 4.5m tonnes of perfectly edible food every year while millions worldwide go hungry. It’s no more or less fair than the way the richest 10% of the world’s population (that’s anyone earning more than £27,000 in Britain) account for over its half of carbon emissions while the poorest end up on the sharp end of the climate crisis.

If Boris Johnson had, once the over-50s were safely jabbed, asked younger British people to wait a few months so doses could be either diverted to countries lagging behind or retained by producer countries in need, he’d probably have faced protests in the streets and on his own backbenches. Look after your own, people would have said: charity begins at home. The more sophisticated version of this would have been that it’s all very sad, but that India’s problems actually flow from its prime minister Narendra Modi’s overconfidence in judging the epidemic more or less over back in March; not our fault. It’s true Modi has much to answer for. But still there is something disturbing about the fact that India is on track for up to half a million cases a day on some projections, while Britons young enough to have practically zero chance of dying from Covid get vaccinated.

I was one of them, a week ago, and remain unbelievably grateful for it. But as a healthy fortysomething woman, I am also uncomfortably aware that I probably wasn’t at high risk; that only a geographical accident of birth makes me this lucky.

Thankfully foreign governments worldwide are now offering oxygen, ventilators, testing kits and drugs to India in its hour of need. But that doesn’t solve harder questions about the hoarding of vaccines, raw materials and patent rights in the west, or the fact that Covax clearly isn’t working as fast as it should. It doesn’t change the fact that nobody is safe until everyone is safe; that nobody really sleeps easy until everybody does.

Gaby Hinsliff is a Guardian columnist

No comments:

Post a Comment