Extract from The Guardian

The rapid rise of capital city house prices in the

past two years has propelled Australia past Denmark with a ratio of

123.08% debt to GDP, analysis shows

House prices have risen 141% in Australia since

1996.

Photograph: David Gray/REUTERS

Photograph: David Gray/REUTERS

Contact author

Friday 15 January 2016 12.41 AEDT

The results are in: Australian households have

more debt compared to the size of the country’s economy than any

other in the world.

Research by the Federal Reserve has shown the

consolidated household debt to GDP ratio increased the most for

Australia between 1960 and 2010 out of a select group of OECD

nations. Australia’s household sector has accumulated massive

unconsolidated debt compared with other countries. As of the third

quarter of 2015, it now has the world’s most indebted household

sector relative to GDP, according to LF

Economics’ analysis of national statistics.

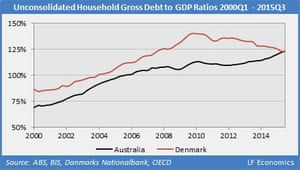

Denmark long held this unholy accomplishment, but

has been slowly deleveraging over the last several years as its

housing bubble peaked and burst during the GFC. The latest

debt-financed boom in Sydney and Melbourne has resulted in

Australia now overtaking Denmark, a comparison of official figures

from Australia and Denmark has shown.

Photograph: LF Economics

Australia has around $2 trillion in unconsolidated

household debt relative to $1.6 trillion in GDP. Australia’s ratio

is 123.08%, while Denmark’s fell slightly to 122.99% in the third

quarter of 2015, a marginal difference of 9 basis points. Although

Denmark holds the record in terms of peak debt of 140.14% in the last

quarter of 2009, as Australia continues to leverage and Denmark

deleverages the current gap between the two will widen. Apart from

Switzerland (which alongside Denmark

has a negative interest rate), no other country is close in terms of

having such extreme household sector debts. The UK ratio is 85.9%

while in the US it is 79.1%.

Due to Switzerland’s opaque financial accounts,

it is impossible to calculate a figure for this quarter. Its ratio

for the second quarter of 2015 is 121.3%, and household debt is

rising very slowly, so it would take an extraordinary increase over

the quarter to potentially beat Australia.

The final confirmation of the trend is expected

when the Bank of International Settlements publishes its analysis of

private credit statistics from the third quarter.

Australian property investors and homeowners are

burdened with massive mortgages, especially new and marginal

entrants. Unlike winning a gold medal at the Olympics, having the

world’s most indebted household sector is not an achievement the

nation should be proud of. This is where Australia’s real debt and

deficit problem lies, not

in the public sector.

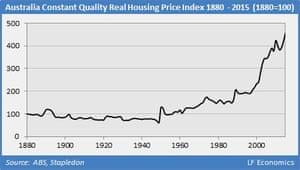

Over the last two decades, Australia has been

beset by rampant housing price inflation.

Since 1996, prices have outpaced fundamentals such

as inflation, incomes, construction costs, rents and GDP, making it

difficult for potential first home buyers to enter the market while

lower income households and marginal groups struggle to afford decent

shelter.

Between 1996 and 2015, housing prices (adjusted

for inflation and quality) have boomed by 141%, without a large and

obvious downturn. This surge has led to a heated debate over whether

this constitutes an asset bubble. Unfortunately, the Australian

housing market shares similarities with countries afflicted by such

bubbles: the United States, Spain, Denmark, the Netherlands and

Ireland.

Government, the FIRE sector (finance, insurance

and real estate) and the mainstream economics profession deny the

existence of a real estate bubble, but Australia’s economic history

demonstrates they occur repeatedly, with all signs pointing to one

today.

Contrary to the analyses of the vested interests,

the data clearly establishes Australia is in the midst of the largest

housing bubble on record.

Photograph: LF Economics

Government is caught between a rock and a hard

place, as implementing needed reforms will likely burst the bubble,

causing severe financial and economic problems as residential land

prices decline. The FIRE sector, including the public caught in the

fallout, will surely blame government for the bust and deflect

attention away from the gargantuan amount of debt pumped out by

lenders.

One of the faults of real estate analysis is the

failure to distinctly define an asset bubble, so debate on the matter

is kept necessarily vague. Only a couple of housing market metrics is

needed to identify a bubble, and are now considered commonplace:

nominal price to inflation, price to income and price to rent. On all

three, Australia is both historically and internationally at or near

the top.

Since the advent of the GFC, it has become

commonly accepted that the global real estate booms originated from

rapidly expanding bank credit or private mortgage debt. It is not

merely the growth of mortgage debt (the first derivative) but the

acceleration (the second derivative), also known as the change in the

rate of growth. Nevertheless, the simple growth of mortgage debt

provides a strong indicator for housing price growth.

The future for investors and new homeowners is not

good. Subdued capital price growth in the secondary capital cities,

rental price growth at record lows, significant dwelling construction

and a falling population growth rate leading to further oversupply

all spell danger. The problems are compounded by the Reserve bank

having little room for interest rate cuts, by weak macroprudential

controls, minimal savings, low household income growth and anaemic

GDP growth.

Captured by neoliberal ideology and the FIRE

sector, government has no interest in stopping this immensely

profitable yet dangerous gravy train, having enriched the already

wealthy beyond avarice through privatisation of unearned economic

rents rather than productive activity.

Philip Soos is the co-author of Bubble

Economics: Australian Land Speculation 1830-2013 and co-founder of LF

Economics. @PhilipSoos

No comments:

Post a Comment