Extract from The Guardian

New study provides one of the strongest cases yet

that the planet has entered a new geological epoch

Fishermen float onboard a boat amid mostly plastic

rubbish in Manila Bay, the Philippines. Humans have introduced 300m

metric tonnes of plastic to the environment every year. Photograph:

Erik de Castro/Reuters

Friday 8 January 2016 06.00 AEDT

There is now compelling evidence to show that

humanity’s impact on the Earth’s atmosphere, oceans and wildlife

has pushed the world into a new geological epoch, according to a

group of scientists.

The question of whether humans’ combined

environmental impact has tipped the planet into an “anthropocene”

– ending the current holocene which began around 12,000 years ago –

will be put to the geological

body that formally approves such time divisions later this year.

The new study provides one of the strongest cases

yet that from the amount of concrete mankind uses in building to the

amount of plastic rubbish dumped in the oceans, Earth has entered a

new geological epoch.

“We could be looking here at a stepchange from

one world to another that justifies being called an epoch,” said Dr

Colin Waters, principal geologist at the British Geological Survey

and an author on the

study published in Science on Thursday.

“What this paper does is to say the changes are

as big as those that happened at the end of the last ice age . This

is a big deal.”

He said that the scale and rate of change on

measures such as CO2 and methane concentrations in the atmosphere

were much larger and faster than the changes that defined the start

of the holocene.

Humans have introduced entirely novel changes,

geologically speaking, such as the roughly 300m metric tonnes of

plastic produced annually. Concrete has become so prevalent in

construction that more than half of all the concrete ever used was

produced in the past 20 years.

Wildlife, meanwhile, is being pushed into an ever

smaller area of the Earth, with just 25% of ice-free land considered

wild now compared to 50% three centuries ago. As a result, rates of

extinction of species are far

above long-term averages.

But the study says perhaps the clearest

fingerprint humans have left, in geological terms, is the presence of

isotopes from nuclear weapons testing that took place in the 1950s

and 60s.

Tower blocks in Hong Kong. More than half of all

the concrete ever used was produced in the past 20 years. Photograph:

Bobby Yip/REUTERS

“Potentially the most widespread and globally

synchronous anthropogenic signal is the fallout from nuclear weapons

testing,” the paper says.

“It’s probably a good candidate [for a single

line of evidence to justify a new epoch] ... we can recognise it in

glacial ice, so if an ice core was taken from Greenland, we could say

that’s where it [the start of the anthropocene] was defined,”

Waters said.

The study says that accelerating technological

change, and a growth in population and consumption have driven the

move into the anthropocene, which advocates of the concept suggest

started around the middle of the 20th century.

“We are becoming a major geological force, and

that’s something that really has happened since we had that

technological advance after the second world war. Before that it was

horse and cart transporting stuff around the planet, it was low key,

nothing was happening particularly dramatically,” said Waters.

He added that the study should not be taken as

“conclusive statement” that the anthropocene had arrived, but as

“another level of information” for the debate on whether it

should be formally declared an epoch by the International Commission

on Stratigraphy (ICS).

Istopes common in nature, 14C, and a naturally

rare isotope, 293Pu, are present through the Earth’s mid-latitudes

due to nuclear testing in the 1950s and 60s. Photograph: Associated

Press

Waters said that if the ICS was to formally vote

in favour of making the anthropocene an official epoch, its

significance to the wider world would be in conveying the scale of

what humanity is doing to the Earth.

“We [the public] are well aware of the climate

discussions that are going on. That’s one aspect of the changes

happening to the entire planet. What this paper does, and the

anthropocene concept, is say that’s part of a whole set of changes

to not just the atmosphere, but the oceans, the ice – the glaciers

that we’re using for this project might not be here in 10,000

years.

“People are environmentally aware these days but

maybe the information is not available to them to show the scale of

changes that are happening.”

The international team behind the paper includes

several other members of the Subcommission on Quaternary

Stratigraphy’s anthropocene working group, which hopes to present a

proposal to the ICS later this year. The upswing in usage of the

anthropocene term is credited to Paul Crutzen, the Dutch Nobel

prize-winning atmospheric chemist, after he

wrote about it in 2000.

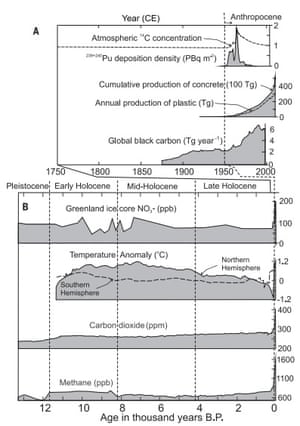

Key markers of change that are indicative of the

anthropocene. A shows new markers, while B shows long-ranging

signals. Photograph: sciencemag.org

Prof Phil Gibbard, a geologist at the University

of Cambridge who initially set up the working group examining

formalising the anthropocene, said that while he respected the work

of Waters and others on the subject, he questioned how useful it

would be to declare a new epoch.

“It’s really rather too near the present day

for us to be really getting our teeth into this one. That’s not to

say I or any of my colleagues are climate change deniers or anything

of that kind, we fully recognise the points: the data and science is

there.

“What we question is the philosophy, and

usefulness. It’s like having a spanner but no use for it,” he

said.

Gibbard suggested it might be better if the

anthropocene was seen as a cultural term – such as as the neolithic

era, the end of the stone age – rather than a geological one.

Evidence we’ve started an ‘anthropocene’

- We’ve pushed extinction rates of flora and fauna far above the long-term average. The Earth is now on course for a sixth mass extinction which would see 75% of species extinct in the next few centuries if current trends continue

- Increased the concentrations of CO2 in the atmosphere by about 120 parts per million since the industrial revolution because of fossil fuel-burning, leaving concentrations today at around 400ppm and rising

- Nuclear weapon tests in the 1950s and 60s left traces of an isotope common in nature, 14C, and a naturally rare isotope, 293Pu, through the Earth’s mid-latitudes

- Put so much plastic in our waterways and oceans that microplastic particles are now virtually ubiquitous, and plastics will likely leave identifiable fossil records for future generations to discover

- Doubled the nitrogen and phosphorous in our soils in the past century with our fertiliser use. According to some research, we’ve had the largest impact on the nitrogen cycle in 2.5bn years

- Left a permanent marker in sediment and glacial ice with airborne particulates such as black carbon from fossil fuel-burning

No comments:

Post a Comment