Extract from The Guardian

A brief burst of Keynes prevented a

1930s-style collapse that might have led to a more fundamental

rethink of the status quo

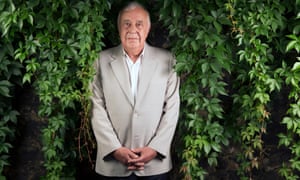

US

Treasury secretary Henry Morgenthau Jr (left) and British economist

John Maynard Keynes conferring during the Bretton Woods international

monetary conference. Photograph: Alfred Eisenstaedt/Time & Life

Pictures/Getty Image

Larry

Elliott Economics editor

Sunday

7 February 2016 23.24 AEDT

Keynes’s General

Theory of Employment, Interest and Money is to economics

what Joyce’s Ulyssesis

to literature: a classic that lots more people start than finish. The

same applies to two other seminal works from the dismal science: Adam

Smith’s Wealth

of Nations and Karl Marx’s Capital.

It

is a fair bet, though, that a good chunk of the Keynes devotees at

last week’s British Academy celebration of the 80th anniversary of

the publication of the General Theory in February 1936 had ploughed

their way through Postulates of the Classical Economy to Notes on

Mercantilism, while only occasionally thinking they would rather be

reading Tinker

Tailor Soldier Spy.

The event pitched

Lord Robert Skidelsky, author of the magnificent three-volume

biography of Keynes, in a debate with Sir Nicholas Macpherson,

shortly to retire as permanent secretary to the Treasury. Its title,

From Keynes to Corbynomics: the General Theory at 80 was a bit of a

misnomer because Skidelsky didn’t dwell on the Labour leader’s

economic ideas and Macpherson said that, as a civil servant, it

wasn’t proper to do so. Instead, the pair took up two themes:

whether Keynes and his ideas had made a comeback following the

financial and economic crisis of 2007-09, and what Keynes would have

made of the handling of the economy by the Treasury since the crash.

Skidelsky

said there had been no lasting return to Keynesian ideas since the

market meltdown, paradoxically because a brief burst of Keynes

prevented a 1930s-style

collapse that might have led to a more fundamental re-think

of the status quo.![]()

This

seems an accurate assessment. The initial response to the crisis

followed Keynes’s ideas pretty much to the letter, with an

assumption that action should be taken to prevent what was clearly

going to be a painful recession turning into a full-blown depression.

Central

banks were the first to act. They sought to make money cheaper and

more plentiful through deep

cuts in interest rates and quantitative

easing. Keynes was primarily a monetary economist who

believed that governments should only turn to fiscal policy - raising

public spending and cutting taxes - when all other options had been

exhausted. Fiscal policy was deployed in 2008-09, but only as a

supplement to monetary policy.

Up to

a point, the strategy worked. There was no second Great Depression

and within six to nine months output had steadied across most of the

global economy. Attempts were then made to return to business as

usual as quickly as possible. That meant reducing the budget deficits

that had ballooned during the recession and making only cosmetic

changes to the debt-driven economic model that had been found wanting

from 2007-09.

Fiscal

policy was relaxed by Alistair Darling during the depths of

the crisis, but the Treasury was already returning to a more orthodox

approach to the management of the public finances even before Labour

left office in 2010. George Osborne then adopted the sort of approach

that would have been followed in the early 1930s: using low interest

rates and QE to boost growth while at the same time cutting spending

and raising taxes in order to rein in the budget deficit.

Macpherson

said the mix of loose monetary policy and tight fiscal policy had

been right, and mounted a robust defence of the Treasury’s

reluctance to run deliberately higher deficits in an attempt to boost

growth. The nine arguments presented included a lack of

“shovel-ready” projects for the government to finance, the fear

that any increase in demand would benefit foreign importers rather

than UK firms, and the likelihood that individuals and businesses

would anticipate that spending increases now would necessitate tax

increases or spending cuts later, and reduce consumer spending and

investment as a result. One questioner asked whether Macpherson was

right to say that Keynes would have approved of the government’s

economic strategy since 2008. “Of course not”, Skidelsky snorted.

So

what would Keynes say if he were still alive today and updating the

General Theory? Firstly, that one of the book’s main themes - the

difference between risk and uncertainty - has been borne out by the

financial crisis. Keynes argued that risk could be quantified but

uncertainty could not, which made all the algorithms that sought to

measure the riskiness of complex financial instruments useless in a

market gripped by panic.

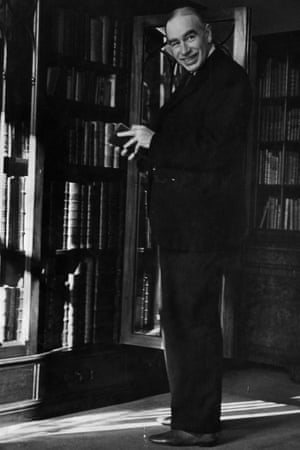

John

Maynard Keynes in his library. Photograph: Tim Gidal/Getty Images

The

second lesson he would draw would be of the need to rethink the way

economics is taught, with a much reduced emphasis on mathematical

models and the restoration to the curriculum of economic history.

His

third conclusion would be that the global financial system has been

made more vulnerable by the stripping away of controls that hindered

the free movement of capital. Supporters of capital liberalisation

argue that it makes financial markets more efficient, but Keynes said

efficient markets were not necessarily effective markets and drew a

distinction between capital used for productive purposes and capital

used for speculation. The story of the years leading up to the crisis

(and the years since, for that matter) is that there was too much of

the latter and not enough of the former.

The

fourth lesson would be contained in a special chapter in the 2016

edition of the General Theory devoted to the eurozone. Keynes would

have been at his most acerbic in detailing the manifold failings of

monetary union, from its flawed

design to the succession of avoidable blunders made by the

European Central Bank and European finance ministers since 2007.

Seeking

an explanation for why the eurozone has performed so poorly in the

past eight years, Keynes would say the answer is simple: the ECB was

not only slow to cut interest rates but

raised them twice in 2011; it took more than half a decade longer

than the US Federal Reserve or the Bank of England to get round to

QE; and, most damagingly of all, European policymakers insisted on

austerity programmes that resulted in still weaker growth and even

higher levels of unemployment. Fiscal policy becomes even more

important in a monetary union, because individual countries give up

the right to set their own interest rates and to devalue (or revalue)

their currencies.

In

the fifth and final lesson, Keynes would seek to explain why the

recovery from the crash had, so far at least, been tentative and

incomplete. His argument would have been that cutting interest rates

to zero and boosting the money supply through QE were enough to

halt the downward spiral in 2009 but not sufficient to bring about a

lasting recovery.

Keynes

would say the way to achieve this would be through a global growth

pact, including more aggressive use of fiscal policy. His detractors

would say what’s needed is a dose of Joseph Schumpeter’s “creative

destruction” so that new, dynamic enterprises can replace

old, inefficient ones. In truth, policy is neither Keynesian nor

Schumpeterian, which is why we are where we are.

No comments:

Post a Comment