Extract from The Guardian

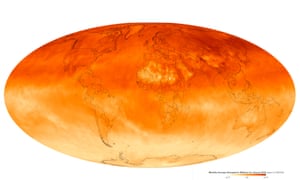

Methane concentrations are higher in the northern hemisphere because both natural- and human-caused sources are more abundant there. Photograph: AIRS/Aqua/Nasa

Fiona Harvey

Tuesday 13 December 2016 00.29 AEDT

Emissions of the powerful greenhouse gas methane have surged in the past decade, threatening to thwart global attempts to combat climate change. Scientists have been surprised by the surge, which began just over 10 years ago in 2007 and then was boosted even further in 2014 and 2015. Concentrations of methane in the atmosphere over those two years alone rose by more than 20 parts per billion, bringing the total to 1,830ppb.This is a cause for alarm among global warming scientists because emissions of the gas warm the planet by more than 20 times as much as similar volumes of carbon dioxide.In the meantime, emissions of carbon dioxide – the main component of manmade greenhouse gases in the atmosphere – have been levelling off. The new research, published in the peer-review journal Environmental Research Letters, suggests that the world’s attempts to control greenhouse gases have failed to take account of the startling rises in methane. The authors of the 2016 Global Methane Budget report found that in the early years of this century, concentrations of methane rose by only about 0.5ppb each year, compared with 10ppb in 2014 and 2015.The scientists speculate that agriculture may be the main source of the additional methane that has been recorded. However, they cannot be sure of all the sources, owing to a lack of monitoring.At least a third of methane comes from the exploitation of fossil fuels, including fracking and oil drilling and some coal mining, where methane is viewed as a waste gas and is frequently allowed to escape or, in some cases, flared off, which is less harmful.Unlike carbon dioxide emissions, however, which have been tracked in various ways since the 1950s, emissions of methane are poorly understood and could represent a threat that scientists have still not accounted for.For instance, the melting of the Arctic tundra releases methane as the vegetation underneath is gradually and sometimes suddenly exposed. This has been regarded by scientists as a potential “tipping point” whereby warming of the Arctic leads to greater releases of methane, therefore greater warming, in a runaway and uncontrollable cycle.Why melting Arctic ice can cause uncontrollable climate change Comparison of methane over Alison Canyon, California, acquired 11 days apart in January 2016 by (left) Nasa’s Aviris instrument on an ER-2 aircraft at 4.1 miles altitude and (right) by the Hyperion instrument on Nasa’s Earth Observing-1 satellite in low-Earth orbit.Although the world’s governments pledged at Paris last year to hold global warming to no more than 2C above pre-industrial levels, few have yet explained in detail how their intentions will be worked out. The president-elect of the US, Donald Trump, has also cast doubt on the US’s future participation in the emissions cuts required.Robert Jackson, professor of earth system science at Stanford University, and a co-author of the paper, warned that methane should also be a key focus of attempts to control climate change.“The levelling off we’ve seen in the last three years for carbon dioxide emissions is strikingly different from the recent rapid increase in methane. Unlike CO2, where we have well-described power plants, almost everything in the global methane budget is diffuse. From cows to wetlands to rice paddies [as well as other sources], the methane cycle is harder.”“Why this change has happened is still not well understood,” added Marielle Saunois, assistant professor at the University of Versailles Saint Quentin, and a lead author of the paper. “For the last two years especially, the growth rate has been faster for the years before. It’s really intriguing.”As well as measures that can be quickly implemented to prevent methane emissions from the fossil fuel industry, ways to cut emissions from agriculture are also being developed and implemented. New breeds of rice require less flooding in paddy fields, new feeds can cut down on emissions from cows, and there are methods of capturing methane from large agricultural barns where livestock are intensively reared. However, few of these are yet widely in operation.

Fiona Harvey

Tuesday 13 December 2016 00.29 AEDT

Emissions of the powerful greenhouse gas methane have surged in the past decade, threatening to thwart global attempts to combat climate change. Scientists have been surprised by the surge, which began just over 10 years ago in 2007 and then was boosted even further in 2014 and 2015. Concentrations of methane in the atmosphere over those two years alone rose by more than 20 parts per billion, bringing the total to 1,830ppb.This is a cause for alarm among global warming scientists because emissions of the gas warm the planet by more than 20 times as much as similar volumes of carbon dioxide.In the meantime, emissions of carbon dioxide – the main component of manmade greenhouse gases in the atmosphere – have been levelling off. The new research, published in the peer-review journal Environmental Research Letters, suggests that the world’s attempts to control greenhouse gases have failed to take account of the startling rises in methane. The authors of the 2016 Global Methane Budget report found that in the early years of this century, concentrations of methane rose by only about 0.5ppb each year, compared with 10ppb in 2014 and 2015.The scientists speculate that agriculture may be the main source of the additional methane that has been recorded. However, they cannot be sure of all the sources, owing to a lack of monitoring.At least a third of methane comes from the exploitation of fossil fuels, including fracking and oil drilling and some coal mining, where methane is viewed as a waste gas and is frequently allowed to escape or, in some cases, flared off, which is less harmful.Unlike carbon dioxide emissions, however, which have been tracked in various ways since the 1950s, emissions of methane are poorly understood and could represent a threat that scientists have still not accounted for.For instance, the melting of the Arctic tundra releases methane as the vegetation underneath is gradually and sometimes suddenly exposed. This has been regarded by scientists as a potential “tipping point” whereby warming of the Arctic leads to greater releases of methane, therefore greater warming, in a runaway and uncontrollable cycle.Why melting Arctic ice can cause uncontrollable climate change Comparison of methane over Alison Canyon, California, acquired 11 days apart in January 2016 by (left) Nasa’s Aviris instrument on an ER-2 aircraft at 4.1 miles altitude and (right) by the Hyperion instrument on Nasa’s Earth Observing-1 satellite in low-Earth orbit.Although the world’s governments pledged at Paris last year to hold global warming to no more than 2C above pre-industrial levels, few have yet explained in detail how their intentions will be worked out. The president-elect of the US, Donald Trump, has also cast doubt on the US’s future participation in the emissions cuts required.Robert Jackson, professor of earth system science at Stanford University, and a co-author of the paper, warned that methane should also be a key focus of attempts to control climate change.“The levelling off we’ve seen in the last three years for carbon dioxide emissions is strikingly different from the recent rapid increase in methane. Unlike CO2, where we have well-described power plants, almost everything in the global methane budget is diffuse. From cows to wetlands to rice paddies [as well as other sources], the methane cycle is harder.”“Why this change has happened is still not well understood,” added Marielle Saunois, assistant professor at the University of Versailles Saint Quentin, and a lead author of the paper. “For the last two years especially, the growth rate has been faster for the years before. It’s really intriguing.”As well as measures that can be quickly implemented to prevent methane emissions from the fossil fuel industry, ways to cut emissions from agriculture are also being developed and implemented. New breeds of rice require less flooding in paddy fields, new feeds can cut down on emissions from cows, and there are methods of capturing methane from large agricultural barns where livestock are intensively reared. However, few of these are yet widely in operation.

No comments:

Post a Comment