Extract from The Guardian

Trump’s instinctual response insisting North Korean development of an ICBM just ‘won’t happen’ and warning China to help may be particularly dangerousTrump seems to be hoping that he can frighten the Chinese government into putting real pressure on Pyongyang. Photograph: Yuri Gripas/Reuters

Julian Borger in Washington

Saturday 15 April 2017 03.14 AEST

The ascent of Donald Trump, the volatility of his foreign policy and his tendency to fire off tweeted threats to nuclear-armed adversaries has brought one more wild card to the Korean peninsular, which already had more than its fair share.

Tensions would be high anyway in the run up to Saturday’s “Day of the Sun”, when the North Korean state celebrates the anniversary of the birth of its founder, Kim Il-sung. His grandson, Kim Jong-un, has shown himself anxious to outdo his forefathers, accelerating the pace of the regime’s missile and nuclear tests.

Very visible work has been under way at the mountainous nuclear test site where a new tunnel has been opened, giving rise to expectations that the country could carry out its sixth underground detonation of a nuclear device. This time, it could be a thermonuclear weapon that is tested, with a far higher yield than a simple fission warhead, or more than one bomb could be set off at the same time.

Photograph: Guardian Design Team

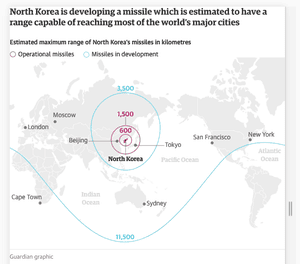

Alternatively, the preparations could be feint, intended to confuse and frighten the rest of the world, and Kim could use the grand military parade on the Day of the Sun to show off an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM), which the regime is seeking to develop and would be capable of reaching the west coast of the US.

There has been little doubt in recent years that the end-point of the North Korean programme is an arsenal of working ICBMs and nuclear warheads small enough to put on top of them. The dilemma of how to stop it reaching that goal is the hardest problem facing any US administration, a point that Barack Obama repeatedly made to Trump during the presidential transition.

How Trump will handle that challenge is the greatest unknown hanging over the region. His instinctual response has been to bluster, mostly on Twitter, insisting that the North Korean development of an ICBM just “won’t happen” and warning that if the Chinese did not do more to stop the forward march of Pyongyang’s programme, “we will solve the problem without them”.

He has described US naval deployments of aircraft carriers and submarines in the region as an “armada”, while his secretary of state, Rex Tillerson, has declared that the Obama era of “strategic patience” is over.

Rattling sabres is a particularly dangerous thing to do on the Korean peninsular. While the repercussions from a missile strike in Syria or the dropping of a giant bomb in Afghanistan can be contained, a preventative strike on North Korea could set off a chain reaction. In wargaming such a confrontation, US military planners under Obama came to the conclusion that Pyongyang’s most likely counter-move would be demolish Seoul with its artillery lined up behind the demilitarised zone separating North and South Korea.

The US and North Korea have thus been stuck in a position of mutual deterrence, which has stopped the outbreak of major new hostilities but not prevented Pyongyang’s steady advance towards the capacity to directly threaten the continental US, and Europe for that matter, with nuclear weapons.

Trump seems to be hoping that by introducing some unpredictability into this static scenario, he can frighten the Chinese government into putting real pressure on Pyongyang. There are some signs that might be working, with hints in China’s semi-official media that Beijing could tighten oil deliveries, North Korea’s lifeline.

If that fails however, and Kim’s instincts up to now have always been to defy pressure, Trump is left with the same dilemma as Obama, but perhaps with even further to walk to any future negotiating table.

No comments:

Post a Comment