Extract from The Guardian

Researchers paint a mixed picture of the controversial program and its role in reducing alcohol and drug use

Last modified on Thu 18 Feb 2021 03.32 AEDT

A government-commissioned evaluation of the cashless debit card has failed to find conclusive evidence the scheme reduces social harm, despite some positive short-term improvements in the trial sites.

The $2m report by the University of Adelaide was released on Wednesday some three months after final drafts were handed to the government and about nine weeks after the trial was extended for two years.

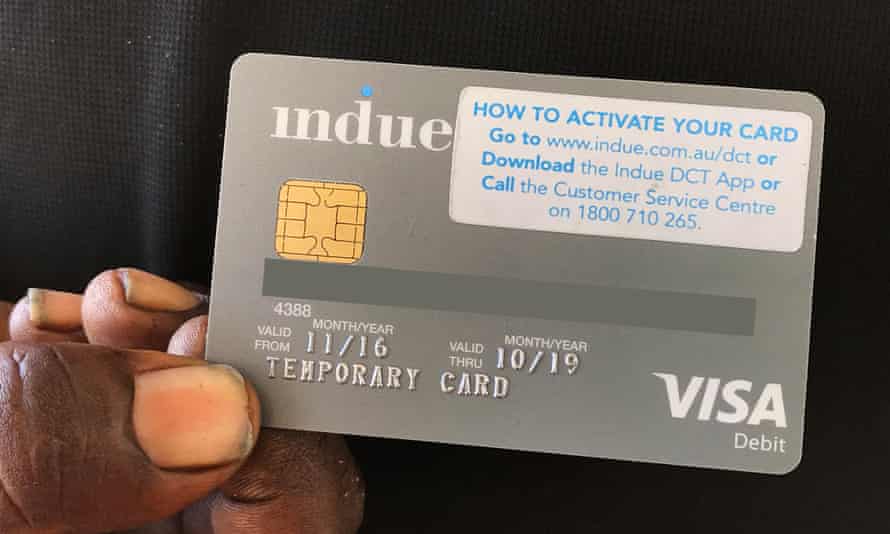

It paints a mixed picture of the controversial scheme, which quarantines up to 80% of welfare recipients’ payment – across four sites – onto a debit card that cannot withdraw cash or be used to purchase alcohol.

Introduced in 2016, the scheme was touted as a way to reduce social harms in areas with large numbers of welfare recipients. It operates in Ceduna, South Australia, the East Kimberley and Goldfields regions of Western Australia, and Bundaberg and Hervey Bay in Queensland.

The aims of the scheme included reducing alcohol and drug use, although the government more recently has also promoted the cashless debit card (CDC) as a “financial literacy” tool for users, who are placed onto the card compulsorily.

In their final 250-page report, the researchers said there was “consistent and clear evidence that alcohol consumption has reduced since the introduction of the CDC in the trial sites”.

“However, with the current evidence, it is not possible to attribute these changes to the CDC alone,” the report said. “They can be attributed, however, to the full complement of relevant policies in the trial areas.”

The evidence was “mixed” and could not reach “any definitive conclusion about whether the CDC influences the personal or social harm caused by the use of illicit drugs”.

The report said there was also “short-term” evidence the CDC had been “helping to reduce gambling, with positive impacts especially in the context of family and broader social life”, but “no longer-term evidence was available”.

Similarly, there was “little consensus about whether and how children’s welfare had changed since the introduction of the CDC in the trial areas”.

“Within the quantitative survey data, most CDC participants reported no major change regarding most aspects of children’s welfare,” the report said.

“A sizeable minority of CDC participants in the quantitative survey reported an overall positive view in relation to changes, while another larger minority reported an overall negative view in relation to changes.”

Other findings included:

On financial management, the card was “reported” to improve life for those “who were probably the most vulnerable”, but it also introduced “widely felt and costly hurdles to many participants in relation to financial planning and money management”.

A “large proportion” of participants said “their quality of life had been affected in a negative way”, though some noted improvements.

Public safety broadly improved in the trial sites, except in the Goldfields where “negative” changes were noted, but the impacts, positive or negative, could not be attributed “to the CDC alone”.

The report broadly aligns with unpublished findings, leaked to Guardian Australia last year, which found “little consensus” the card was fulfilling its intended aims in one of the trial sites, the Goldfields in Western Australia.

The Greens senator Rachel Siewert said on Wednesday the report found “nothing definitive to back up the grand claims the government has been making about this scheme for many years now”.

“As

I recall, the cashless debit card was going to get people to find work,

stop gambling, stop drinking and stop taking illicit drugs,” she said.

“Their evaluation supports none of these grand claims.”

“The

evaluation is quite clear that it is not possible to attribute changes

in trial sites to the cashless debit card alone. This evaluation is full

of qualifiers like ‘complex findings’ and that ‘the findings from this

evaluation are mostly nuanced and specific, that is, they are findings

that may apply up to a point and for some people, but not for others’.”

She noted the researchers had found that under the current circumstances most participants would prefer to opt out of the card trial.

There were also “feelings of discrimination, embarrassment, shame and unfairness as a result of being on the card” reported “across all trial sites by a majority of CDC participants”.

The report said 61% of all participants in the three trial evaluated sites were Indigenous, including 82% in the East Kimberley region and 74% in Ceduna.

The scheme also operates in Bundaberg and Hervey Bay, which was not evaluated by the researchers and where the Indigenous population is much lower.

The federal government controversially refused to release the research before seeking to make the scheme permanent late last year.

Instead, facing defeat in the Senate, the government managed to extend the program for two years with the support of Centre Alliance.

Rex Patrick, an independent senator, had considered voting for the government’s bill, but ultimately decided there was not sufficient evidence despite the fact the card had been operating since March 2016.

No comments:

Post a Comment