Extract from The Guardian

The British prime minister wrote to his Australian counterpart to explain why he was denied a speaking slot in December.

Last modified on Wed 24 Mar 2021 15.26 AEDT

Boris Johnson has told Scott Morrison Australia was denied a speaking slot at a leaders’ climate ambition summit in December because his government had not set ambitious commitments to address the climate crisis.

In a sign of the growing international pressure over climate, the British prime minister also indicated he expected Australia to this year set a timeframe to meet net zero greenhouse gas emissions and increase its short-term commitments – steps the Morrison government continues to resist.

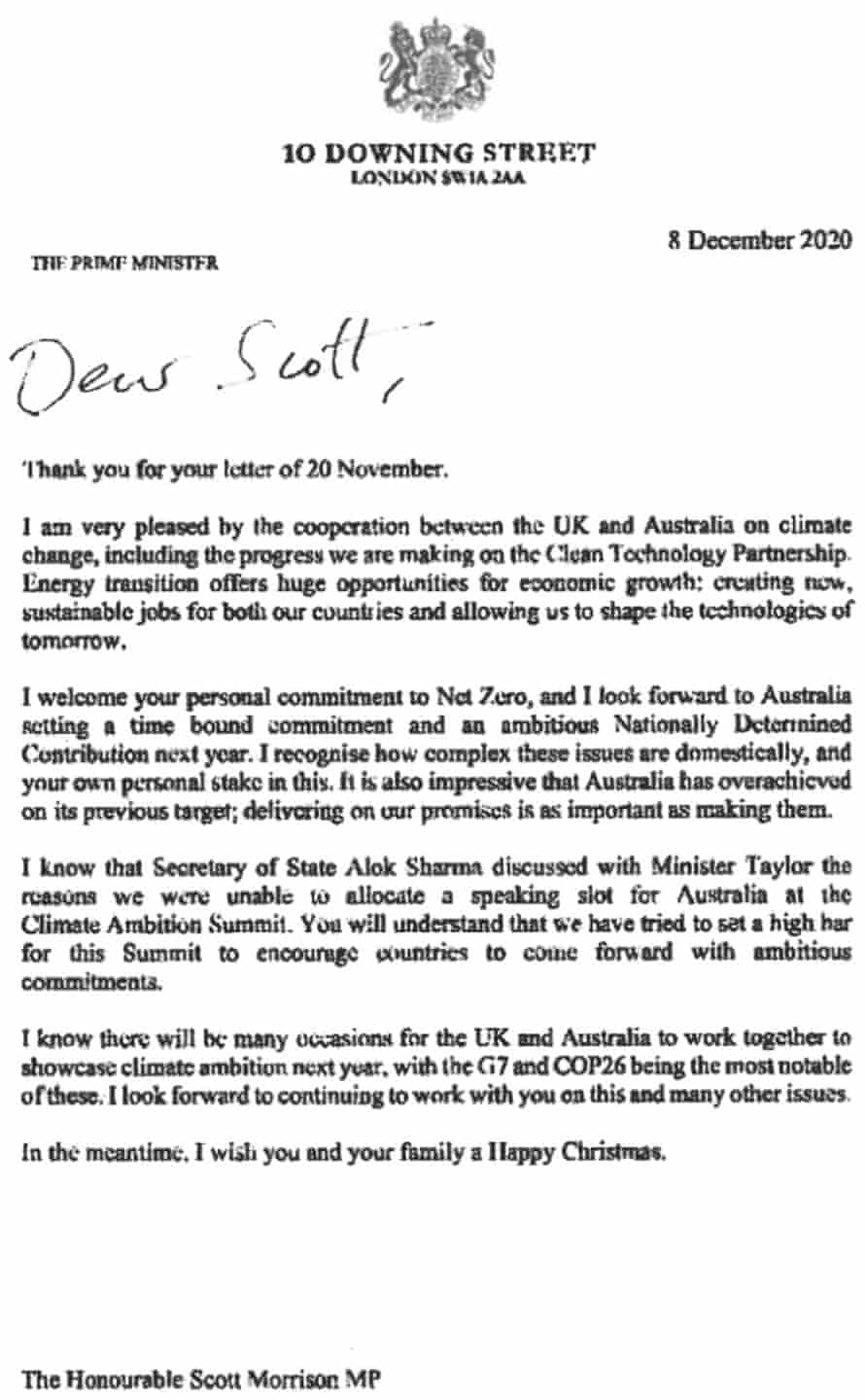

The comments were included in a letter dated 8 December, four days before the summit, that was tabled in a Senate estimates hearing in Canberra on Monday night.

Johnson indicated the British president of the next major climate summit in Glasgow, Alok Sharma, had told Australia’s emissions reduction minister, Angus Taylor, why Morrison had not been allocated a speaking berth.

“You’ll understand that we have tried to set a high bar for this summit to encourage countries to come forward with ambitious commitments,” he wrote.

Morrison was embarrassed by the summit rejection, having earlier told the Australian parliament he would use his appearance to “correct mistruths” about his government’s oft-criticised record on emissions reduction.

The summit was hosted by the UK, France and the United Nations. Diplomatic sources said the French, in particular, believed Morrison should not receive a slot given he had not met any of the four criteria that had been set for countries to be allowed to speak.

As reported by the Guardian, the organisers had earlier written to national leaders saying speaking slots would be given only to leaders who set stronger 2030 targets to cut emissions, announced a long-term strategy to reach net zero emissions, committed new financial support for developing countries or had ambitious plans and policies to adapt to locked-in climate change impacts. They had warned there would be “no space for general statements”.

Morrison had reportedly wanted to use the summit to say Australia no longer expected to use controversial “carryover credits” to meet its 2030 emissions target. He ended up making a similar statement in an online event with Pacific leaders that week.

Australia’s plan to use the credits was diplomatically contentious, and other countries did not see a pledge to potentially drop it as an ambitious step. Dozens of nations opposed their use at the last major climate summit in Madrid on the grounds they do not represent new emissions cuts. A former French environment minister, Laurence Tubiana, said it suggested Australia was “cheating” on the Paris agreement.

In his letter, Johnson said he was “very pleased” by the cooperation between the UK and Australia on climate, including progress on a clean technology partnership.

He said he welcomed Morrison’s “personal commitment” to net zero emissions, adding: “I look forward to Australia setting a time bound commitment and an ambitious nationally determined contribution [short-term commitment] next year [2021].”

Johnson said he recognised “how complex these issues are domestically” – a reference to the division within the Australian Coalition government over acting on the climate crisis – and Morrison’s “own personal stake in this”.

“It is also impressive that Australia has overachieved on its previous target; delivering on our promises is as important as making them,” he wrote.

The last reference was to Australia reaching and exceeding the targets it set under the previous Kyoto Protocol.

Those targets were an 8% increase in emissions between 1990 and 2012, and a 5% cut between 2000 and 2020. Neither reflected what scientific advice said was necessary for Australia to play its part in addressing the problem, but the Morrison government has argued it showed the country had a track record of delivering on commitments where other countries had not.

Australia is facing rising pressure to set a goal of meeting net zero emissions no later than 2050. More than 100 countries have set this target, and it is backed by Australian state governments and many business and community leaders. Morrison has said only that he wants to reach net zero as soon as possible, and “preferably by 2050”.

While the 2050 target remains a point of dispute, Britain and the US are increasingly focused on encouraging countries to set more ambitious 2030 goals before the Glasgow conference, known as COP26.

The US president, Joe Biden, is hosting a major economies’ leaders summit on 22 April in a bid to build momentum, and has promised to unveil an ambitious 2030 target beforehand.

Britain and the European Union last year set targets of a 68% and 55% cut by 2030 compared with 1990 emissions levels respectively. Canada and Japan are expected to set new 2030 goals before a G7 meeting in Cornwall in June.

The British hosts have invited the leaders of Australia, India and South Korea to join all sessions at the G7 summit, in part in a bid to push them to do more on climate.

Australia’s 2030 emissions target is a 26-28% cut below 2005 levels. Scientists and analysts have calculated the target should be roughly doubled if Australia was to play its part under a global net zero goal.

No comments:

Post a Comment