Extract from Eureka Street

- Tim Dunlop

- 04 May 2021

I first started reading about universal basic income (UBI) more than ten years ago, and my interest was based in concerns of equality, fairness and wealth redistribution. UBI wasn’t well-known at the time, but there was a literature about it, and a group of keen advocates out in the world making the case.

Around 2013, UBI went from the margins into the mainstream of debate, and the key impetus was increasing concern about the displacement of human workers by various forms of automation, a concern largely prompted by a report from the Oxford Martin School.

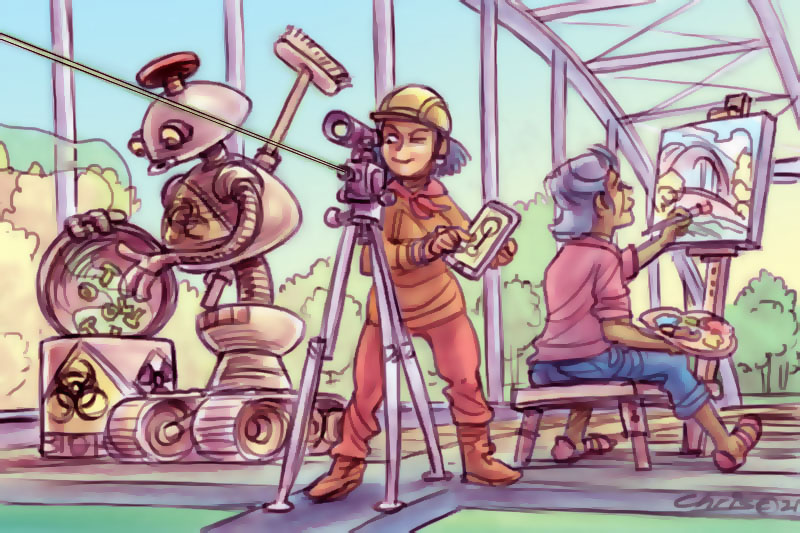

Unfortunately, the debate about the future of work, and therefore UBI, was hijacked by a reductive media narrative around ‘the robot question’ — will a robot take my job? — and this has made it hard to recognise the complex nature of the changes underway. So let’s try to clarify.

Left to itself, automation will destroy jobs, entire industries in fact, but it will also generate new forms of work, as has happened in the past. The concern was that this new work would be poorly paid, insecure and deeply unsatisfying, and that it would concentrate wealth in the hands of a few as the labour share of national income (wages) dropped or stagnated.

Experts like John Falzon have noted this is more or less what has happened, and the COVID-19 pandemic has complicated matters further.

The issue is not automation and technology per se, but how we respond to it. Instead of just letting business maximise their bottom line, we, as a democratic nation, should use all the tools at our disposal to manage the deployment of technology and the social changes that arise. UBI can be one of those tools.

'So the key point for me is that UBI isn’t simply reactive, a response to technological unemployment. It is transformative, opening up possibilities.'

The detailed arguments about work and automation are beyond the scope of this article, but the crux of it is that the nature of work itself is fundamentally changing and we need to recognise that. Automation, artificial intelligence, and various platform technologies are radically transforming what work is, and this means we have to think differently about how it is defined and compensated.

I think it is fair to say earlier advocates of UBI presented an overly simplistic version of the scheme that took little account of the politics of implementation. This left them vulnerable to cooptation by right wing proponents of what was called UBI, but was actually more like a negative income tax. UBI critics on the left were wise to be wary of this form of basic income, to see it as a Trojan Horse for the destruction of service provision more generally, as the way of paying for UBI.

But there is no reason UBI can’t be designed and instigated as an adjunct to traditional welfare, not as a replacement for it.

Rather than being a rightwing Trojan horse, then, UBI can be a way of decentring market understandings of work and replacing them with a broader and more accurate idea of what it means to be a worker in contemporary society. It allows us to refocus our attention on people themselves, rather than on jobs per se.

In a paper now published by the Crawford School at the ANU, my co-authors and I provide a way of rethinking of what it means to work in society, and we set out what we call a Liveable Income Guarantee.

'We propose…(work) contributions are reframed according to ability. Productive contributions would therefore include child-raising, study, volunteering, artistic and creative activity, community and ecological care. Disability payments should continue at age pension rates, recognising people’s contribution to society, while the age pension would continue as a recognition of past contributions.

We define a Liveable Income Guarantee as an income:

i) sufficient to sustain a decent standard of living over time

ii) available without punitive conditionality

iii) paid to everyone without an adequate market income who is willing and able to contribute to Australian society.'

Services are not enough. There has to be a cash element to welfare so that individuals can make their own decisions about how they balance paid work and the other aspects of their lives, the contributions they make outside the parameters of the traditional labour market.

There are risks with rethinking work in this way, and Per Capita Senior Fellow, John Falzon, told Eureka Street, ‘I do think we need to reconfigure social security to address the precarity of paid work, but not as a means of accepting this precarity.’

He remains sceptical of UBI saying, ‘I am concerned that the UBI model could mean a further atomisation of the working class and a weakening of its bargaining power, not only industrially but socially.’

These are valid concerns, but I don’t think they are fatal to the idea of UBI.

Our recent experience with lockdown and various JobKeeper type payments has shown unequivocally how valuable it is to provide people with an ongoing cash payment. In fact, research at the Crawford School showed JobKeeper/Seeker virtually eliminated poverty in Australia for key groups. Why would we only do that during a pandemic and not make it an ongoing feature of our society?

Most of us want to participate meaningfully in society and be able to support ourselves in the process, but at least some of that participation can and must happen outside conventional notions of the job market. Unless we can pursue non-market forms of participation absent the fear of poverty, we are not truly free.

So the key point for me is that UBI isn’t simply reactive, a response to technological unemployment. It is transformative, opening up possibilities. Being able to access it unconditionally at any time in your working life frees people to make other decisions about the way they participate in society.

UBI doesn’t presume we are put on the earth merely to have a job, that our existence is dependent on someone paying us a wage. It doesn’t discourage anyone who wants that sort of work from doing it (as trial after trial shows), but it does allow for the fact that having a job is not a defining human characteristic. Work may be, but having a market-based job, especially a poorly paid, insecure one under someone else’s control, isn’t, and our welfare system needs to recognise that fact.

UBI allows us to differentiate between work and participation, helping free us from the tyranny of market expectations.

Tim Dunlop is an author who has written extensively on Universal Basic Income and the future of work. His books, Workless (2016) and The Future of Everything

(2019) deal with both topics, and he has been a keynote speaker at

national and international events on these subjects, including the 2019

Tim Dunlop is an author who has written extensively on Universal Basic Income and the future of work. His books, Workless (2016) and The Future of Everything

(2019) deal with both topics, and he has been a keynote speaker at

national and international events on these subjects, including the 2019

No comments:

Post a Comment