Extract from The Guardian

The fact YouTube had to step in and do what Acma should have done a year ago is an indictment of a broken system.

Last modified on Sat 7 Aug 2021 06.02 AEST

When Sky News was suspended for seven days by YouTube this week for videos that breached their rules about Covid-19 misinformation, people naturally asked what Australia’s broadcasting regulator was doing.

The answer was: nothing discernible. Why? That opens a large and difficult question.

The Australian Communications and Media Authority, which is responsible for holding broadcasters to account, was set up in 2005. Where content issues are concerned it is a “co-regulator”. That means it must deal with these issues in cooperation with the broadcasting industry. It is a recipe for regulatory capture and that is exactly what has happened.

This is not a reflection on the people who have tried to make it work for the past 16 years. It is a reflection on the Howard government, which set it up, and on successive governments on both sides who have been content to leave Acma hamstrung and prey to the uniquely effective pressure that media organisations can exert on politicians and government agencies.

Acma is an amalgam of the Australian Broadcasting Authority and the Australian Communications Authority. The ABA was likewise a co-regulator of broadcasting content, while the ACA was basically concerned with communications infrastructure.

Acma inherited the ABA system that had already been described by the Productivity Commission as being closer to self-regulation than co-regulation. A report to the ABA by a consultant in 2004 stated that there were “serious deficiencies” in the remedies available to it.

All this was a consequence of a deliberate policy choice of the Keating government to adopt a more market-based, less interventionist approach to broadcasting regulation. The explanatory memorandum attached to the Broadcasting Services Act 1992 specifically states that the role of the regulator is to be “an oversight body ... rather than an interventionist agency”.

This was a big win for the commercial broadcasters who were sick of being held to account by the more powerful and hard-nosed Australian Broadcasting Tribunal, which the act replaced with the ABA.

Along the way, the “fit and proper person” test for a broadcasting licence was quietly replaced by a much vaguer and less exacting test of “suitability”.

Thus the signal sent to the ABA and Acma by successive governments was: “Go easy on the commercial broadcasters.” In reality this has meant that the commercial television and radio industries have written their own codes of practice, which are rubber-stamped by Acma.

These loosely worded and threadbare documents make it easy for a licensee to slip through their many loopholes or argue for interpretations that place their conduct in a defensible light.

Allied to this is a highly legalistic process of investigation. Acma’s complaints reports are a maze of definitions and interpretations in which the substance of the original misconduct gets ground down to the point where something that started out looking serious ends up looking trivial.

Occasionally the process also produces a perverse outcome.

Take the case of David Campbell. He was New South Wales transport minister. To entrap him, Channel Seven had set up surveillance cameras opposite a club for homosexual men in Sydney. Campbell was caught on camera driving to the club in his ministerial car, which he was entitled to do. Confronted with the footage, Campbell resigned. Channel Seven nonetheless then broadcast the footage, and this led to complaints being lodged with Acma.

That’s right: Channel Seven invaded his privacy, it caused Campbell to resign, and his resignation then created the public-interest justification for broadcasting the footage.

Or take the case of the Christchurch massacre in 2019. Sky News Australia, and through it Sky New Zealand, used a combination of still images and video/audio excerpts from the gunman’s body camera, including gunfire directed at a person. This was found to breach the broadcasting standards in both countries.

The New Zealand regulator imposed a $NZ4,000 penalty on Sky New Zealand, even though it had no effective control over the feed from Australia. Acma decided it would engage in a “productive conversation” with Sky News Australia.

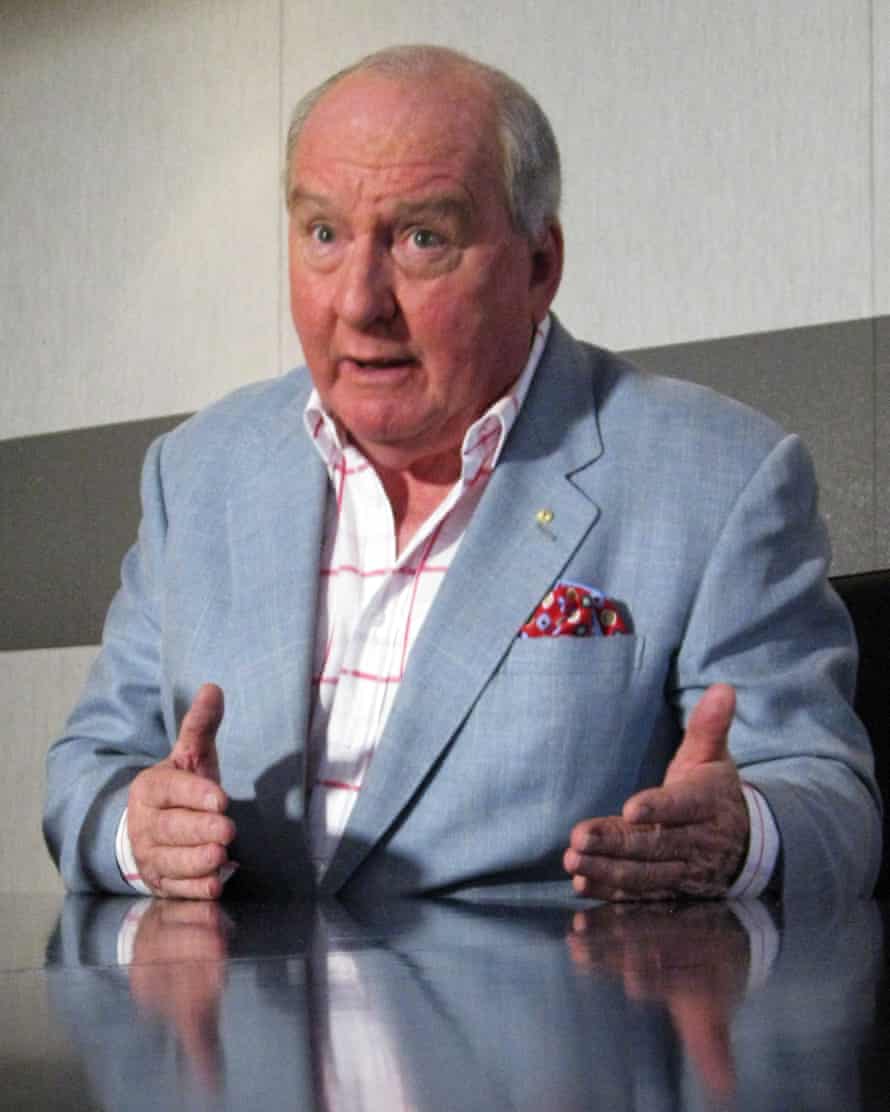

So where was Acma when Sky was broadcasting misinformation about Covid-19? Perhaps contemplating another “productive conversation”, just as it has on innumerable other occasions when the egregious Alan Jones has yet again been found in breach of the codes.

That a social media platform like YouTube has to step in and do what the Acma should have done a year ago when Jones and his cohorts on Sky started on this irresponsible path, is an indictment of a broken system.

Meanwhile, although suspended by YouTube, Sky News continues to broadcast on free-to-air regional television thanks to its newly minted deal with Southern Cross Austereo and the continued paralysis of Acma.

No comments:

Post a Comment