Extract from The Guardian

The impact of the proposed price caps seems clear. Power bills will increase, but they will be lower than they otherwise would be in the absence of government intervention. Consumer rebates are still a bit of a work in progress, requiring final agreement between the treasurer Jim Chalmers and his state counterparts.

While energy has dominated the headlines since October, other important policy conundrums are gathering speed as we stagger towards the summer break. The Albanese government has been pushing ahead in diplomacy, security and in defence policy.

This week, Labor’s Clare O’Neil reset key priorities in the national security portfolio most associated with Scott Morrison and Peter Dutton – home affairs.

During a speech to the National Press Club, O’Neil, the current home affairs minister made it clear she would retire the made-for-2GB-mantras of stop the boats and bad bikies. Replacing them? A sharper focus on cyber security, a new civics and social cohesion program to address misinformation and threats to democracy, and greater coordination around the natural disasters intensified by the climate crisis.

While O’Neil was hosing out hoary chestnuts from home affairs, the defence minister Richard Marles and the foreign minister Penny Wong met their counterparts in the United States.

This week’s “Ausmin” discussion in Washington hung a lantern over the growing US military presence in Australia. The talks this week also moved Australia closer to operationalising the Aukus nuclear submarine pact, while working through how to solve the yawning capability gap that exists in the interim.

Let’s open with a Saturday morning mind bender about Aukus. Readers: do we think the Albanese government would have initiated the Aukus agreement if Anthony Albanese and Co had been in government during the last parliamentary term?

I think about this sliding doors question periodically. It’s interesting to me, because I don’t know the answer. Sometimes I think it must be no. Other times, I think, given the dangerous state of the world, all roads lead all Australian governments to an Indo-Pacific nuclear submarine junction.

While we are playing hypothetical, it’s important to be clear. Labor did have an opportunity to say no to Aukus back in opposition. Albanese did not have to endorse Morrison’s plan. Paul Keating counselled against it. But the political risk of resistance was high.

With an election bearing down, Morrison was absolutely desperate to create a point of difference with his political opponents – so desperate that he ultimately escalated and branded Marles a “Manchurian candidate” in the parliament. This conduct was so unbecoming Canberra’s intelligence establishment emerged from the shadows and rebuked Morrison in plain sight.

So we know what happened.

Labor said yes to Aukus, which draws Australia ever deeper into the military complex of the US. As well as the rolling to-and-fro about Aukus, this week Australian ministers in Washington agreed to “preposition stores, munitions, and fuel in support of US capabilities in Australia” and agreed to “increase rotations of our air, land and sea forces”.

The general atmospherics of the week suggest the Albanese government is journeying deeper down the US integration path with few, if any, qualms. But I’d caution readers against a one-dimensional reading of events.

A reading that says the Albanese government, in a brain dead partisan risk aversion trance, is all the way with Uncle Sam, does miss an important nuance.

Australia is absolutely saddling up with the US – a choice that was made long before we entered the current era of Chinese militarism and nationalism. Australia made this choice years before we could see the possibility of a military conflagration over Taiwan.

But that doesn’t mean Australia isn’t hedging our bets. If we look past the razzle dazzle of Ausmin and Aukus to the looming defence strategic review, the important nuance comes into focus.

This arms-length review, established by Albanese and Marles, and reporting early next year, is an exercise in establishing whether or not Australia can defend itself in light of current threats. The process is examining defence force structure, posture and preparedness. It will consider what sort of investments Australia should make if we want to be able to defend the country against sudden lethal aggression.

At one level, the policy question the review asks is entirely routine. All responsible governments make provision to defend their territory against hostile incursions. Governments also adjust those plans in the light of evolving threats, and expert assessments of the capability of adversaries.

But given Australia sits under the military umbrella of the US, and given the government seems to be walking even further down that road, why is the same government asking a pointed policy question that goes right to the heart of our national sovereignty?

Here’s a theory. Perhaps the government is asking that question because we can no longer fully rely on the US to be a reliable security partner.

Now don’t get me wrong. Joe Biden has certainly revived the US as a responsible global citizen that respects the value of alliances. But how long is Biden there? How long before the reactionaries break back? The resurgence of populist isolationism in the US casts a long shadow across world. If I were Albanese, I’d want insurance against the whims of Donald Trump 2.0, or Ron DeSantis – or whomever.

In an interesting interview with the Australian back in November, Albanese was direct about his intentions.

He said Australia needed missiles, and drones, and enhanced cyber capabilities. He flagged increasing Australian military capability within five years. He said he wanted the strategic review to provide advice about the optimal means of self defence. More than this, Albanese said Australia needed to “project force” – quite the declaration from a life-long leftwinger from inner-city Sydney.

The moral of the story this weekend is things are generally more complicated than they look. Australia is going further into the US military complex, while hedging our bets. And if we look to defence’s policy companion, diplomacy, we see mirrored complexity.

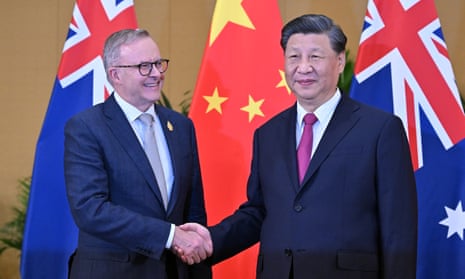

Over the past six months, the Albanese government has managed to stabilise the relationship with Beijing. This has happened because China has chosen to resume open diplomacy, and because Labor has sought to lower the temperature in the theatre of domestic politics. This relational reset with China has happened at the same time as the government has made our increasing integration with the US more explicit. It’s also coincided with a Wong-led soft-power offensive in the Pacific which is all about repelling Chinese influence.

Australia has turbo-charged diplomacy while simultaneously signalling our inclination to strengthen deterrence. These two objectives are superficially contradictory, but as Marles put it in a speech earlier this year: “The idea that Australia has to choose between diplomacy and defence – or, as some critics would have it, between cooperation and confrontation – is a furphy, and a dangerous one at that”.

So where does all this leave us?

The simple answer is in a quantifiably different place to the past three years, where foreign and defence policy was very often crafted as a kabuki play for a domestic audience. When a government’s international statecraft is tuned for the TV news and talkback radio, to amplify intra-day partisan messaging, things are simple.

There are goodies and baddies, and heroes and villains; rinse and repeat.

The change of government has reset the terrain. We are now back to Australia prosecuting foreign and defence policy for its own ends, in a dangerous world.

The cross-currents will be strong enough at times to feel a bit scary, and a bit confusing. But it’s all pretty interesting.

I recommend we all fasten our seat belts, secure our tray tables, and watch how our fate in the region is reshaped over the next 12 months.

No comments:

Post a Comment