Extract from The Guardian

The actor, who plays a serial killer in new BBC drama Rillington Place, talks about the rise of ‘fascism’ in the US, the abuse he suffered as a child and why he cares only about reviews from the staff in his local supermarket

It is a balmy afternoon in Pasadena, California, with winter sunshine flooding the hotel terrace. Tim Roth exudes a dash of dandy in a knee‑length vintage black coat. The illusion dissolves when he chucks it over a chair – revealing a wrinkled black T‑shirt, old jeans and stained black boots – plonks in a chair and orders a beer. He could be an off‑duty plumber.

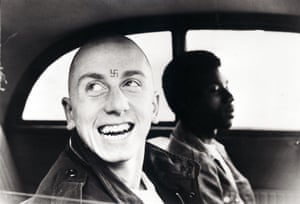

He lights up a vape and proceeds to puff minty clouds. “Kids got me on to it, years ago, to get me off the fags. It works, but I vape too much.” The Londoner is 55 and wears it well: hair swept back, trim beard, relaxed. Over three decades, he has played memorably tormented characters who suffer or inflict suffering; a vicious skinhead in Alan Clarke’s Made in Britain (1982); an apprentice assassin in Stephen Frears’ The Hit (1984); a literal abomination in The Incredible Hulk; a psychotic simian general in Planet of the Apes; bloodied or hapless characters in Quentin Tarantino’s Reservoir Dogs, Pulp Fiction and The Hateful Eight. Likewise, he is usually tragic or villainous in indies and TV gigs.

Yet Roth remains an enigma. He lives quietly with his family in Pasadena, a leafy part of Los Angeles. He avoids the celebrity circuit and is wary of the media; he has a reputation as a prickly interviewee. But today he proves gregarious and gracious, even when he is raging about the president-elect.

He lights up a vape and proceeds to puff minty clouds. “Kids got me on to it, years ago, to get me off the fags. It works, but I vape too much.” The Londoner is 55 and wears it well: hair swept back, trim beard, relaxed. Over three decades, he has played memorably tormented characters who suffer or inflict suffering; a vicious skinhead in Alan Clarke’s Made in Britain (1982); an apprentice assassin in Stephen Frears’ The Hit (1984); a literal abomination in The Incredible Hulk; a psychotic simian general in Planet of the Apes; bloodied or hapless characters in Quentin Tarantino’s Reservoir Dogs, Pulp Fiction and The Hateful Eight. Likewise, he is usually tragic or villainous in indies and TV gigs.

Yet Roth remains an enigma. He lives quietly with his family in Pasadena, a leafy part of Los Angeles. He avoids the celebrity circuit and is wary of the media; he has a reputation as a prickly interviewee. But today he proves gregarious and gracious, even when he is raging about the president-elect.

“I hate Trump. I hate everything that he stands for. He should never be forgotten or forgiven for anything he said on the road to the White House. There should be no concession to him. No ‘Let’s give him a chance’. None of it,” he says. “‘Grab them by the pussy,’ right? Look at where we are now and who is in charge of this country and, by extension, a good chunk of the world – someone with misogynistic tendencies.”

Roth rooted first for Bernie Sanders, then Hillary Clinton (although, as a non-citizen, he could not vote). He says he predicted a Trump victory early on. “If you neglect the working class for so fucking long they will rebel against you. There was a dire need to stop a rise of fascism in America and we didn’t take it seriously enough.”

This leads to discussion of Roth’s journalist father, Ernie Smith. He grew up dirt poor, fought in the war with the RAF, changed the family name to Roth, partly in solidarity with Jews, and joined Britain’s Communist party. He quit the party in the 1970s, Roth recalls, partly over sex scandals that appalled him. “He was an abused kid, my dad, and it was a terrible childhood that he had, and he took that shit seriously.”

I am startled. When Roth made his directorial debut, The War Zone (1999), based on Alexander Stuart’s novel about a father abusing his daughter, he revealed, without much elaboration, that he had been abused as a child. Now he is saying his dad was, too?

He nods. “He was a damaged soul. I loved him. He was funnier than fuck.” He puffs on the vape. “He was abused. And I was abused. But I was not abused by him. I was abused by his abuser.”

The same abuser?

“Yeah. It was his father.” Roth’s grandfather. His voice drops. “He was a fucking rapist. But nobody had the language. Nobody knew what to do. That’s why I made The War Zone.”

Roth looks out at the hotel gardens. A few minutes earlier, they were green and sunlit. As if on cue, rainclouds appear and turn everything grey. In one especially horrifying scene in The War Zone, the camera is motionless, an impassive observer, as the father rapes his daughter. Some festival audiences walked out.

Roth closes the subject and our conversation moves on. But clearly the theme still draws him, because he may tackle abuse in his second directorial outing – a film about child welfare services set in 1980s New York. He may also direct a Harold Pinter script of King Lear and reprise Trevor the skinhead in a sequel to Made in Britain.

He left London in 1991. He fears the UK is heading down a dark path. “I like working there, but I’m done living there. I fell out of love with it. I think the tabloid sensationalism world of it just became too overwhelming for me. It’s here, too, but you don’t notice it so much. And now with Brexit ... I don’t know what to make of it all. Strange thing.”

‘A psychotic simian general’: Roth as Thade in Planet of the Apes. Photograph: Ronald Grant Archive

Pressed, he continues. “It’s been taken over. It’s The X Factor, Murdoch, Rebekah Brooks, Tony Blair nature of it all.” He fancies Jeremy Corbyn, who may peel off his usual vote for the Greens, but he plans to remain in the US, even though he cannot vote here. “I can handle this a bit better, weirdly. There are a lot more lefties out here.”

LA has not dented his use of south London idioms, nor induced airs about acting. “The methodists? Not interested in any of it. I don’t take acting as seriously as people expect me to. I used to think I should. I thought you were supposed to live and breathe it.”

This approach probably helps when playing psychos (he was once slated to play a young Hannibal Lecter). “It used to be that I’d have all the [research] detritus lying around the house and my wife would freak out. Now, it’s all on computer, so I can just close it and it all goes away. It doesn’t affect me. I don’t carry my work around with me at all. When you’re preparing is when it’s difficult. But once you start it’s easy to switch it all off.” And once filming wraps? “Have a good shower, move on.”

He is currently appearing on TV playing a real monster: John Christie, the seemingly meek serial killer who strangled at least eight women and hid the bodies in his house and garden in London between 1943 and 1953.

Roth studied the archives. “A lot was tabloid sensationalism. But there were also police records, interviews with people who knew him, from local prostitutes to family members.”

Christie was from the Midlands and spoke in a whisper, prompting Roth and a dialect coach to cast around for a particular accent and tone to help channel the sociopath. Step forward son of Leeds Alan Bennett. “It was one of the voices we found that really helped,” says Roth.

He tilts his head, adopts a strange smile and does the voice. “His very quiet voice, very comforting, very sweet, here, have a cup of tea.” The effect is deeply creepy, not least because Bennett is a beloved playwright and arguably the least menacing man in Britain.

“We shot a lot more than they showed in terms of what he did, what he liked, what he did to women. What’s interesting is that the neighbours liked him and the local kids liked him. He played a gentle, old, quite respectable fellow. That was the character. But it was not him.”

Roth zig-zagged to Hollywood. He studied sculpting at Camberwell College of Arts before switching to acting, a decision emboldened by Ray Winstone’s depiction of a borstal tough in Scum (1979). “I watched it again and again, back to back, and thought: ‘If he can do that, I can do that.’ When you see a performance like that coming from a background like that, it makes it possible for you.”

Roth felt part of a working-class wave – Winstone, Kathy Burke, Gary Oldman, Phil Davis and Steve Sweeney, among others – crashing through Britain’s thespian portals. “It was an extraordinary thing ... none were toffs.”

They thrived, but the gates seemed to shut behind them. The wealthy and middle class now dominate Britain’s creative industries. “Rich people have a safety net ... so they can afford to fail, they can afford to be unemployed, which is most of what you are when you’re an actor,” says Roth. “I’m not sure it’s about the toffs so much as cost. You’re in debt for fucking life if you want to go to drama school. The government isn’t going to support you any more; that’s all over. There are no grants.”

That said, the eldest of his three sons, Jack, the product of a relationship with writer and producer Lori Baker, works as an actor in London. “He makes his own way, pays his own way. But it’s hard,” says Roth. He groans and laughs when asked about Jack’s choice of career. “Please don’t do that, oh God. It’s kind of funny, really – all my boys are in the arts.” Nikki Butler, a fashion designer whom Roth married in 1993, is the mother of his other sons.

He bears no grudges against toffs, singling out Rupert Everett as “hugely delightful”. He shoots down the internet rumour that he would like to name a hippo Colin as a riposte to Colin Firth bagging leading roles. “Colin is one of my favourite names to name dogs,” he says, wryly. Flinty political statements aside, Roth says he can respect and work with anyone. “My father-in-law is a Republican. He’s one of the most decent men I’ve ever met. He’s a good human being. I work with Scientologists; it doesn’t matter to me. I work with Catholics; Jesus, figure that one out. If people are good, they’re good. If they have different political convictions, it’s irrelevant, unless they’re harmful. If they can bend a bit ... I think you’re all right.”

When he moved to California, he discovered a niche. “Everyone had to be pretty; in movies, that was the deal. That was why they were boring. I thought: ‘There’s a hole in the market for proper character actors again.’” Directors such as Tarantino, James Gray and Steven Soderbergh concurred. “They employed me. It was unbelievable. You didn’t have to look like a matinee idol, you could actually be human.”

Roth has to get his kit off in an upcoming project, he confides, bemused why anyone would want “to look at a 55-year-old geezer”, but he feels it is almost a duty to show his flaws on screen. “You want to have real men, not fake men ... none of that gym culture.” He pities hostages to six-pack tyranny. “If beauty is your worth, or that version of beauty is what you’re paid for, you have to keep that fucking up.” Ryan Gosling, for one, is too savvy to be trapped, he says. “He’s used it well and will absolutely escape that nonsense. Fortunately, I make a living not out of that.”

On cue, a waiter brings another beer. But Roth, let it be noted, has no hint of a gut.

A Zelig-type arc through US film saw him co-star with Tupac Shakur in the comedy drama Gridlock’d, filmed not long before the rapper’s murder in 1996. “I loved him,” he says. “He was an actor, firstly, before he was a rapper.” He nicknamed Tupac New Money for his flashy lifestyle. “His nickname for me was Free Shit, because I’d take anything that was free – T-shirts, anything that was going.”

That impulse has ebbed, but Roth still frets about paying bills. “Fear of unemployment drives actors. If I couldn’t make the payments on the house, I’d be in trouble.” He did a commercial in Japan before A-listers bagged those gigs. “I was a genie, I came out of the instant coffee. All I had to do was stand in a studio in front of a green screen. Sam Jackson has that tied down now. George Clooney, too. There are jobs you do for yourself and there are jobs that you do for money. The ones you do for yourself and your creative needs generally are the ones that don’t pay. So you have to balance it out.”

Which brings us to United Passions, last year’s critically reviled paean to Fifa – “A disgrace ... excrement,” said the Guardian – in which Roth played Sepp Blatter, since ousted in a corruption scandal.

Roth takes a long puff and sighs. “The Fifa thing was school fees, college fees, all of that. That was: ‘Fuck it, man, you know what, I’ve got to do this, got to pay the rent and got to look after the boys.’ So, that’s what that was. I’m sure I was soundly criticised for it, as I should have been.”

He paid penance during the World Cup in Brazil, he says, by shunning Fifa-supplied VIP tickets. “For every match. Every one. And it was just too embarrassing to go.” He laughs. “How fucked up was that? That’s the price for playing a guy like that.”

Roth says he does not read his own press, nor watch his own films. “I stopped reading reviews 15 years ago. It’s kind of great. And often I don’t see the things I’m in. I just move forward.” Except for that time at Cannes when a red-carpet scrum swept him into a screening of Grace of Monaco, in which he played Prince Rainier III.

“It was received quite well by the audience, but the reviews were already out and we got slaughtered. But I couldn’t get out of it. I normally turn up, say hi and fuck off. I got stuck. It was the most disturbing night. Not because the film was particularly bad or anything, and I loved working with Nicole [Kidman], but I just don’t like looking at myself. What’s the point? Film is a directors’ medium.”

He shrugs off accusations of occasional hamming up. “I get criticised for that, but I don’t fucking care. The audience can either switch of or engage. It’s up to them. It’s for the audience. I’m not the audience. But I’m sure I get slagged a bit. Maybe I should.”

The only critics he cares about, besides his wife and children, are staff at his local supermarket. “I was there yesterday, did a major shop. I love doing the shopping. All the guys there know me. I get my reviews from them. They’re quite honest.”

Killers, skinheads, gangsters, princes – whatever the gig, he tries to nail it for them. “I derive great satisfaction from their pleasure if I get my job right. There’s nothing like entertaining folk.” Most unRothian statements. He shrugs and laughs. “It sounds so corny, but that’s all right, because I won’t read it anyway.”

Episode two of Rillington Place is on BBC1 on Tuesday at 9pm

No comments:

Post a Comment