It was a coal town, predicted to be wiped out by the closure of two

ageing power plants. Now Port Augusta has 13 renewable projects in train

by Adam Morton

by Adam Morton

The

largest solar farm in the southern hemisphere lies on arid land at the

foot of the Flinders Ranges, more than 300km north of Adelaide. If that

sounds remote, it doesn’t do justice to how removed local residents feel

from what currently qualifies as debate in Canberra.

As government MPs and national newspapers thundered over whether taxpayers should underwrite new coal-fired power, mauling advice from government agencies as they went, residents of South Australia’s Upper Spencer Gulf region have been left to ponder why decision-makers weren’t paying attention to what is happening in their backyard.

"What’s happening here is going to be happening on the eastern seaboard in the next 10 years."

In mid 2016, this region was on the brink, hit by the closure and near collapse of coal and steel plants. Now it’s on the cusp of a wave of construction that investors and community leaders say should place the region at the vanguard of green innovation – not just in Australia but globally. There has been an explosion in investment, with $5bn spread over the next five years. There are 13 projects in various stages of development, with more than 3,000 construction and 200 ongoing jobs. The economy of this once-deflated region has been transformed and those who live here are starting to feel hopeful again.

The Port Augusta mayor, Sam Johnson, a 32-year-old former Liberal member, is continually surprised at how resistant some are to the idea that the energy environment has changed. “You might choose to ignore what’s happening here now because we’re out of sight, out of mind, but the reality is that what’s happening here is going to be happening on the eastern seaboard in the next 10 years,” he says.

In simple terms, the Upper Spencer Gulf transition story goes like this. Port Augusta was a coal town, home to the state’s only two lignite – or brown coal – plants, Playford B and Northern. Playford B, ageing and failing, was mothballed in 2012. Northern, the larger and younger of the two, closed in May 2016 when owner Alinta Energy decided it was no longer economically viable. The Leigh Creek mine that supplied it, by then offering up mostly low-quality coal, shut at the same time. About 400 workers at the plant and the mine lost their jobs. Roughly a third retired, a third found other employment locally and a third had to leave town to find work.

At the same time, further around the gulf, the steel town of Whyalla was teetering precipitously after the owner, Arrium, put the mill in voluntary administration facing debts of more than $4bn.

As government MPs and national newspapers thundered over whether taxpayers should underwrite new coal-fired power, mauling advice from government agencies as they went, residents of South Australia’s Upper Spencer Gulf region have been left to ponder why decision-makers weren’t paying attention to what is happening in their backyard.

"What’s happening here is going to be happening on the eastern seaboard in the next 10 years."

In mid 2016, this region was on the brink, hit by the closure and near collapse of coal and steel plants. Now it’s on the cusp of a wave of construction that investors and community leaders say should place the region at the vanguard of green innovation – not just in Australia but globally. There has been an explosion in investment, with $5bn spread over the next five years. There are 13 projects in various stages of development, with more than 3,000 construction and 200 ongoing jobs. The economy of this once-deflated region has been transformed and those who live here are starting to feel hopeful again.

The Port Augusta mayor, Sam Johnson, a 32-year-old former Liberal member, is continually surprised at how resistant some are to the idea that the energy environment has changed. “You might choose to ignore what’s happening here now because we’re out of sight, out of mind, but the reality is that what’s happening here is going to be happening on the eastern seaboard in the next 10 years,” he says.

In simple terms, the Upper Spencer Gulf transition story goes like this. Port Augusta was a coal town, home to the state’s only two lignite – or brown coal – plants, Playford B and Northern. Playford B, ageing and failing, was mothballed in 2012. Northern, the larger and younger of the two, closed in May 2016 when owner Alinta Energy decided it was no longer economically viable. The Leigh Creek mine that supplied it, by then offering up mostly low-quality coal, shut at the same time. About 400 workers at the plant and the mine lost their jobs. Roughly a third retired, a third found other employment locally and a third had to leave town to find work.

At the same time, further around the gulf, the steel town of Whyalla was teetering precipitously after the owner, Arrium, put the mill in voluntary administration facing debts of more than $4bn.

Yet as the doom hit, there were also rays of hope as several clean power projects were mooted for the surrounding area.

Two years on, the Port Augusta city council lists 13 projects at varying stages of development. And Whyalla has unearthed a potential saviour in British billionaire industrialist Sanjeev Gupta, who not only bought the steelworks but promised to expand it while also spending what will likely end up being $1.5bn in solar, hydro and batteries to make it viable.

Gupta says the logic behind his investment in solar and storage is simple: it’s now cheaper than coal.

Johnson says he expects the Upper Gulf region to receive $5bn in clean energy investment over the next five years. “My gut feel – and I’m an optimist – is that they will all go ahead,” he says. “They are different technologies and they are playing in different markets, so they are not competing for power purchase agreements.”

By any measure, the Bungala solar power plant is vast. Once its second stage is complete, 800,000 photovoltaic modules will cover an area the size of the Melbourne central business district. The scale is neatly summarised by Chris Rowe, the plant’s operations manager and, with maintenance officer Andrew Bartsch, our tour guide around the site. Both men recently returned to Port Augusta after working away to take up positions with Enel Green Power. One day Rowe decided to stroll back from the 275MW farm’s outer edge, weaving in and out of the rows of panels as he went. By the time he got back to his office, he had covered 12km. “At that point I thought, ‘gee, this is really something’,” he says.

Bungala is nearing completion, with work on the $425m plant expected to be finished by January. Its first section started feeding into the national electricity grid in May. Further west, ground has been broken on the 59-turbine, 212MW Lincoln Gap wind farm, though progress has temporarily stalled after developer Nexif Energy discovered unexploded ordnance from historic military testing on site.

At Cultana, just north of Whyalla, Energy Australia is investigating building the country’s first saltwater pumped hydro energy storage plant. It would draw water from the Spencer Gulf, pump it uphill when energy is plentiful and cheap, and convert it to hydro electricity at times of high demand. A decision on the project is expected in 2019.

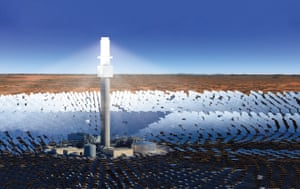

All are potentially agenda setting, but none are as anticipated as the Aurora solar thermal power station. It is the culmination of a push that began in 2010. A research paper by advocacy group Beyond Zero Emissions formed the basis for the creation of Repower Port Augusta, a community group that built widespread support for bringing the developing technology to the region among councils, business and unions.

US developer SolarReserve took notice. It plans to use a field of mirrors to heat a molten salt system inside a 234-metre tower. It will both generate electricity and store eight hours of energy that can be sent out when the sun isn’t shining. The company says the $650m plant, to be built at the Carriewerloo sheep station about 30km north of Port Augusta, will be the world’s largest solar tower with storage and provide 5% of the state’s energy needs.

The SolarReserve vice-president, Mary Grikas, stresses the plant will operate “just like a conventional coal or gas power station, reliably generating electricity day and night – except without any emissions”.

With the increasing emphasis on “firming” power to back up variable renewables, solar thermal is seen as a potentially major player in filling the gaps, along with other fast-starting options such as pumped hydro, lithium-ion batteries and peaking gas. The 150MW Aurora plant is underpinned by a 20-year power supply contract with the South Australian government, but the company is still to finalise a $110m concessional loan with the federal government, the result of a deal with former senator Nick Xenophon in return for his support for company tax cuts.

Dan Spencer worked on the solar thermal campaign as an activist with the Australian Youth Climate Coalition and Solar Citizens, relocating from Adelaide for six months to help build local support. Now a campaigner with the Australian Services Union, he is still pinching himself that it is set to become a reality. “The transition from coal hasn’t been perfect, but in a couple of years we will be seeing this incredible project that people not that long ago thought was just pie in the sky,” he says. “The local community really deserves the credit.”

Aurora is not the only solar-thermal project linked to the region. Port Augusta is already home to a small concentrated solar-thermal plant owned by Sundrop Farms that it uses to run a hydroponic greenhouse that provides Coles with tomatoes.

Also on the horizon, and just as unique design-wise, is a proposal by Solastor, chaired by former Liberal party leader John Hewson. It promises new graphite-based technology to capture solar energy and store it in a load-shifting battery. Hewson says it will be a world-class project. “Solar thermal will take the market, there’s no doubt about that,” he says.

Why are developers choosing the Upper Spencer Gulf? Investors say it has several things going for it: great sunshine; a history of electricity generation that left strong connections into the national grid; nearby industry – particularly mine developments – demanding reliable energy; strong facilitating support from the Weatherill Labor government that has continued under the new Liberal premier, Steven Marshall.

Ross Garnaut is a former Labor climate policy adviser who is now the president of Zen Energy, a solar and battery firm that has projects in the region and is 51% owned by Gupta.

“The Upper Spencer Gulf happens to be a very good place to start,” Garnaut says. “Some coal generation regions have good renewables and others don’t, and no others have them as good as Port Augusta. [But] the Port Augusta developments could be replicated in any region that has good solar and wind resources.”

The inclusion of solar thermal is crucial as it means jobs on a semi-industrial scale. Wind and solar photovoltaic plants bring plenty of jobs in construction, but few in operation. Solar thermal has more in common in operation with coal, using steam to spin a turbine. SolarReserve expects to have a 50-strong permanent workforce at the Aurora plant.

It is an important point. While enthusiasm about the new projects in the gulf is high, the shift away from coal has not been seamless – less a transition than a period of loss followed by rebirth. There remains significant disappointment, in some cases anger, about what some consider the unnecessary pain caused by a failure to plan for life after coal.

Gary Rowbottom is a case in point. A mechanical technical officer at the town’s power stations for 17 years, he joined the Repower Port Augusta campaign in 2012 and became the public face of the campaign. He was persuaded that solar thermal was the future and hopeful Alinta would be persuaded to embrace the technology to replace coal. He says he was naive about how easy that would be. When the company announced Northern’s closure earlier than expected, he was 55 and left hunting for work.

Fifty job applications and 11 interviews later, he was still looking. After about 18 months he left town to take a position on a coal plant in central Queensland. He now sees his wife, Debbie, only every couple of months.

“It’s not been ideal,” he says. “I did my best to get a job that would have kept me home. I guess it was hurting me financially, watching my redundancy steadily getting eroded away, and I had a growing sense of failure. I worry that others are going through the same thing.”

Rowbottom is buoyed by the developments under way at home, and hopeful the Aurora solar thermal plant will provide his ticket back. “It’s great it is happening. We just wish it could have happened a bit sooner,” he says. “What is hard for many of us to understand is why the closure couldn’t have been organised as a proper transition.”

Johnson, who ran unsuccessfully for Xenophon’s SA Best party at the state election, says Port Augusta is set to be the renewable energy capital of the country, with more ongoing jobs if all proposed projects in the Upper Spencer Gulf go ahead than at the former coal plant.

But he says both the former Labor state and current Coalition federal governments failed to offer the community the support it needed when the coal plant closed. The ramifications of the rapid closure were significant. Some small businesses and shut. Dirt and coal ash continue to blanket Port Augusta when the wind blows from the south-east because the former coal plant site was not properly rehabilitated. Wholesale electricity prices across the state increased more than they would have had more significant replacement generation been readied earlier.

“I’d love for people to learn from what’s happened here [about] what not to do when you’re closing a power station,” Johnson says.

Whyalla seems to have fewer issues in the wake of Gupta’s arrival in July 2017. Seeing a business opportunity that governments and publicly listed companies did not, he promised to initially spend $1bn to double the steel mill’s production and convert it to a “green steel” model he has applied in other countries. This includes using more recycled steel and investing heavily in clean energy close to the plant. He is spending $700m building two farms of solar panels, a cogeneration plant to convert the waste gases from steel production into electricity, the country’s largest lithium-ion battery and up to three pumped hydro plants in disused mining pits in the Middlebank Ranges. He says more will follow.

Both Gupta and Johnson say the message for the rest of the country is: embrace change.

Gupta says: “Be braver. Be more entrepreneurial. Take risks … It is very difficult to change things in Australia. Everyone is too stuck in their ways.”

Johnson says: “You can resist change as much as you like, but the reality is, if you’re in a community that has a coal-fired power station, its days are numbered. The market is dictating that change whether we like it or not.

“My advice is: learn from the Port Augusta experience. I wish the federal government would.”

No comments:

Post a Comment