Extract from The Guardian

A bohemian whose work was often censored, Norman Lindsay’s book of

delightfully nasty characters and superb illustrations became a beloved

children’s classic

“Eat

away, chew away, munch and bolt and guzzle/Never leave the table till

you’re full up to the muzzle.” This sage advice comes, of course, from

Norman Lindsay’s The Magic Pudding, a classic children’s book

celebrating its centenary this year.

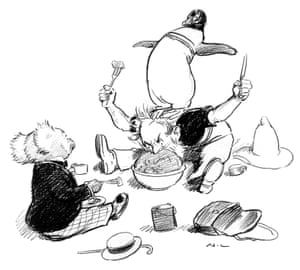

Famously, the book emerged from a dispute about what attracted children to reading. His friend Bertram Stevens claimed kids loved fairies; Lindsay insisted they craved food. Publisher Angus and Robertson glossed the volume that resulted as detailing the “Walks, Talks, Travels, Exploits, Fights, Stratagems and Sing-songs of Bill Barnacle (a Sailor), Sam Sawnoff (a Penguin) and Bunyip Bluegum (a Native Bear), told in prose and verse … and illustrated in 100 pictures.”

At its heart lies Albert, the Puddin’ at whom, Bill tells the astonished Bunyip, “me an’ Sam has been eatin’ away … for years, and there’s not a mark on him.” The book’s longevity suggests Lindsay correctly estimated the appeal to a “cut-an-come again” pudding, particularly one that changed with a whistle from steak-and-kidney to plum duff. But The Magic Pudding’s success might also be taken as confirmation of Stevens’ argument, given Albert manifests all the wilfulness traditionally associated with elves, sprites and similar creatures.

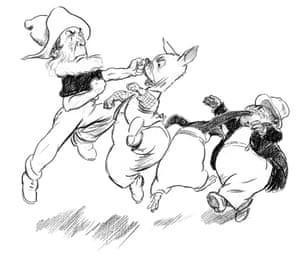

When Bill and Sam explain to Bunyip their possession of “this remarkable Puddin’”, they tell of their shipwreck on an iceberg. There, an obese cook named Curry and Ice concocts “in a phantom pot/a big plum-duff an’ a rump-steak hot” – but refuses to share with his starving shipmates.

Famously, the book emerged from a dispute about what attracted children to reading. His friend Bertram Stevens claimed kids loved fairies; Lindsay insisted they craved food. Publisher Angus and Robertson glossed the volume that resulted as detailing the “Walks, Talks, Travels, Exploits, Fights, Stratagems and Sing-songs of Bill Barnacle (a Sailor), Sam Sawnoff (a Penguin) and Bunyip Bluegum (a Native Bear), told in prose and verse … and illustrated in 100 pictures.”

At its heart lies Albert, the Puddin’ at whom, Bill tells the astonished Bunyip, “me an’ Sam has been eatin’ away … for years, and there’s not a mark on him.” The book’s longevity suggests Lindsay correctly estimated the appeal to a “cut-an-come again” pudding, particularly one that changed with a whistle from steak-and-kidney to plum duff. But The Magic Pudding’s success might also be taken as confirmation of Stevens’ argument, given Albert manifests all the wilfulness traditionally associated with elves, sprites and similar creatures.

When Bill and Sam explain to Bunyip their possession of “this remarkable Puddin’”, they tell of their shipwreck on an iceberg. There, an obese cook named Curry and Ice concocts “in a phantom pot/a big plum-duff an’ a rump-steak hot” – but refuses to share with his starving shipmates.

Bill stops his song midway. “There’s a verse left out here,” he says, “owin’ to the difficulty of explainin’ exactly what happened when me and Sam discovered the deceitful nature of that cook”.

The Puddin’ will have none of it. “I had my eye on the whole affair,” he replies, “and it’s my belief that if he hadn’t been so round you’d have never rolled him off the iceberg, for you was both singing out, ‘Yo heave Ho’ for half-an-hour, an’ him trying to hold on to Bill’s beard.”

Norman Lindsay might seem a rather unlikely author of a treasured book for children, given that, throughout the 20th century, the government censor repeatedly banned his work for obscenity.

When, for instance, the conservative Argus discussed his 1930 novel Redheap, the reviewer concluded: “all the characters are warped and some of them are bestial. These creatures wallow in dirt until the book ends after a number of episodes possibly unrivalled in repulsiveness.”

The product of one of those extraordinary families blessed with multiple talented members (think of the Mitfords or Pankhursts), Norman joined, while only a teenager, his older brother Lionel in Melbourne’s bohemia. They lived so impecuniously among the youthful painters of the 1890s that a member of the city’s larrikin gangs once bailed them up demanding to know the lurk by which these “artists” so successfully avoided work.

During the war years, Lindsay supplied The Bulletin with jingoistic cartoons lambasting wicked Huns, pacifists and socialistic shirkers.

Later, the judge presiding over a trial of Puddin’ thieves in the town of Toolaroo calls another character “an unmitigated Jew”. It’s a reminder of Lindsay’s attachment to some of the nastier prejudices of his era – as, for that matter, is his depiction of koalas, bandicoots and other native animals adventuring through a landscape as entirely white and exclusively male.

Yet we should also acknowledge that Lindsay’s otherwise unfortunate enthusiasm for Nietzsche, Wagner and similar thinkers gives The Magic Pudding its distinctive sensibility.

In 2000, Hollywood produced a film version, with John Cleese providing the voice of the Puddin’. IMDB puts a glossy sheen on it, describing a narrative of “an old man, a young anthropomorphic koala, a South Pole penguin and Albert, a magic sentient walking and talking bowl of pudding with an attitude … searching for the koala’s missing parents.”

I take no shame to fight the lame

When they deserve to cop it.

Or do not try to pipe your eye,

Or with my flip I’ll flop it.

As for Bunyip, he’s not searching for his parents but escaping his Uncle Wattleberry, offended by the older bear’s flowing whiskers. The characters express, in other words, Lindsay’s own disdain for wowserism and milksop Christianity. They enjoy instead the simple pleasures of eating, singing and fighting; they’re eternally vigilant about those who would take their Puddin’ by force or by guile.

They inhabit, we might say, the moral universe of every younger sibling who worries about a brother snatching the dessert. Indeed, the book exudes a child’s unabashed joy in wordplay, rhyme and badinage. Bill, in particular, anticipates by several decades the beloved Captain Haddock of Tintin fame.

“Of all the swivel-eyed, up-jumped, cross-grained sons of a cock-eyed tinker,” he says to a bad-tempered bird, “if punching parrots on the beak wasn’t too painful for pleasure, I’d land you a sockdolager on the muzzle that ud lay you out till Christmas”.

Lindsay’s serious art hasn’t aged well, by and large, with many of his once-scandalous paintings striking modern eyes as vaguely silly. But his superb illustrations for The Magic Pudding capture perfectly the delightful nastiness of his characters. We recognise the swag-carrying Parrot as a disreputable boozer, but he’s somehow still an actual bird.

The book ends with the Judge repeatedly clouting the Puddin’ thieves with a bottle of port, as he sings, “As I find great satisfaction/Hitting anybody who/Can offer that distraction/Why, I’ll have a go at you.” As for the Puddin’ owners, they make a home in a tree belonging to a “grave, elderly dog named Benjimen Brandysnap”, with Albert corralled in “a little Puddin’ paddock” from which he can shout rude remarks at the people passing by, a habit, the narrator explains, to which he’s particularly prone.

Happy birthday, Albert! May you enjoy “throw[ing] bits of bark at the cabbages and pull[ing] faces at the little pickle onions in order to make them squeak with terror” for another hundred years or more!

• A 100th anniversary edition of The Magic Pudding is out now through HarperCollins. An exhibition of original drawings from The Magic Pudding is showing at the State Library of NSW until 24 February 2019

• Jeff Sparrow is a Guardian Australia columnist

No comments:

Post a Comment