Extract from The Guardian

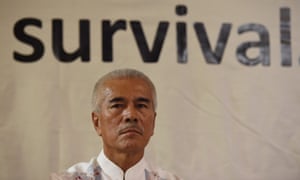

Anote Tong, allegedly insulted by Australian minister, says inaction means Canberra risks losing its status in Pacific region

Anote Tong has had quite a week. The former president of Kiribati has been in Australia to advocate for more robust action on climate change, which threatens to wipe out his Pacific home within a matter of decades as sea levels rise.

But on Wednesday he got caught up in controversy when reports emerged that Australia’s environment minister, Melissa Price, allegedly told him it was “always about the cash” when Pacific Islands leaders came to Australia.

"It’s about lives, it’s about the future"

As a result, Tong has become hot property. When we meet in the late afternoon the next day he has been on the go since 4am with interviews and meetings.

While Price’s alleged comments have given him prominence, they have also threatened to derail his message about the impact of climate change on Kiribati and what countries such as Australia should be doing to help.

Tong says he did not hear the comments Price is alleged to have made at a restaurant. “I do have a hearing problem. I’m a free diver and I lost my hearing [in one ear],” he says. “If it was true that those were the comments then I would not be happy.”

Mostly, Tong just wants to move on. “We’ve gone beyond that, I don’t want to go back. I’ve had a call from the minister, which I thought was very gracious of her to do that, just saying if I have offended you in any way I assure you it was not my intention.”

Tong has other criticism for the environment minister and her colleagues. He was angered by their reactions to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report last week, which said the world had just 12 years to limit global warming to a maximum of 1.5C. Price said it would be “irresponsible” for Australia to commit to phase out coal by 2050, while the deputy prime minister, Michael McCormack, said Australia would not change policy based on the recommendations of “some sort of report”.

“I was not happy. I was very disappointed when the credibility of the report was being questioned, because there is no alternative science being put forward and what’s at stake is not minor,” said Tong. “It’s not about the marginal rise in price or reduction in price of energy, it’s about lives, it’s about the future.” If Australia, which has been criticised by its Pacific neighbours for failing to take more concerted action to reduce emissions, does not change its tone, Tong says it is in danger not only of losing its position as a regional leader but of being welcome in regional organisations at all.

“When countries in the region do things that are not proper, like have a coup, we expel them from the regional body … When you believe somebody is destroying your future and your home, what should you do?”

For Kiribati, the impacts of climate change are being felt acutely, with increased storms and flooding. Rising sea levels mean it is inevitable the island will disappear, says Tong. “If it doesn’t happen in 20 years’ time, it’ll happen in 50 years’ time or in 100 years’ time.”

When people have to leave Kiribati, Tong does not want them to leave in an emergency situation or as climate change refugees – a term he dislikes. Instead, he says, governments should be training people in countries such as Kiribati that are feeling the brunt of climate change so they can get jobs elsewhere, which Tong calls “migration with dignity”.

“We have more than enough time to make our people qualified,” he said. “It has already worked. We had a Kiribati-Australia nursing initiative, where our young people were trained in Queensland and they found jobs in Australia.”

By one estimate from an Oxfam report last year, the sea-level rise resulting from 2C of warming could submerge land that is currently home to 280 million people. Each year from 2008 and 2016 an average of 21.8 million people were reported as newly internally displaced by extreme weather disasters such as cyclones.

Tong says Kiribati and other countries like it are “owed” the resources to train their people so they can relocate. “If I drop a tree on your home and I come to you and say ‘where are you going to live?’ [you’re] going to say: ‘I’m going to live with you until my home is fixed.’ That’s the normal thing, isn’t it? Otherwise I think I take you to court. Now we don’t have that remedy, but I think the principles are essentially the same.”

But on Wednesday he got caught up in controversy when reports emerged that Australia’s environment minister, Melissa Price, allegedly told him it was “always about the cash” when Pacific Islands leaders came to Australia.

"It’s about lives, it’s about the future"

As a result, Tong has become hot property. When we meet in the late afternoon the next day he has been on the go since 4am with interviews and meetings.

While Price’s alleged comments have given him prominence, they have also threatened to derail his message about the impact of climate change on Kiribati and what countries such as Australia should be doing to help.

Tong says he did not hear the comments Price is alleged to have made at a restaurant. “I do have a hearing problem. I’m a free diver and I lost my hearing [in one ear],” he says. “If it was true that those were the comments then I would not be happy.”

Mostly, Tong just wants to move on. “We’ve gone beyond that, I don’t want to go back. I’ve had a call from the minister, which I thought was very gracious of her to do that, just saying if I have offended you in any way I assure you it was not my intention.”

Tong has other criticism for the environment minister and her colleagues. He was angered by their reactions to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change report last week, which said the world had just 12 years to limit global warming to a maximum of 1.5C. Price said it would be “irresponsible” for Australia to commit to phase out coal by 2050, while the deputy prime minister, Michael McCormack, said Australia would not change policy based on the recommendations of “some sort of report”.

“I was not happy. I was very disappointed when the credibility of the report was being questioned, because there is no alternative science being put forward and what’s at stake is not minor,” said Tong. “It’s not about the marginal rise in price or reduction in price of energy, it’s about lives, it’s about the future.” If Australia, which has been criticised by its Pacific neighbours for failing to take more concerted action to reduce emissions, does not change its tone, Tong says it is in danger not only of losing its position as a regional leader but of being welcome in regional organisations at all.

“When countries in the region do things that are not proper, like have a coup, we expel them from the regional body … When you believe somebody is destroying your future and your home, what should you do?”

For Kiribati, the impacts of climate change are being felt acutely, with increased storms and flooding. Rising sea levels mean it is inevitable the island will disappear, says Tong. “If it doesn’t happen in 20 years’ time, it’ll happen in 50 years’ time or in 100 years’ time.”

When people have to leave Kiribati, Tong does not want them to leave in an emergency situation or as climate change refugees – a term he dislikes. Instead, he says, governments should be training people in countries such as Kiribati that are feeling the brunt of climate change so they can get jobs elsewhere, which Tong calls “migration with dignity”.

“We have more than enough time to make our people qualified,” he said. “It has already worked. We had a Kiribati-Australia nursing initiative, where our young people were trained in Queensland and they found jobs in Australia.”

By one estimate from an Oxfam report last year, the sea-level rise resulting from 2C of warming could submerge land that is currently home to 280 million people. Each year from 2008 and 2016 an average of 21.8 million people were reported as newly internally displaced by extreme weather disasters such as cyclones.

Tong says Kiribati and other countries like it are “owed” the resources to train their people so they can relocate. “If I drop a tree on your home and I come to you and say ‘where are you going to live?’ [you’re] going to say: ‘I’m going to live with you until my home is fixed.’ That’s the normal thing, isn’t it? Otherwise I think I take you to court. Now we don’t have that remedy, but I think the principles are essentially the same.”

No comments:

Post a Comment