Extract from The Guardian

The Australian Academy of Science warns that limiting global heating to the Paris goal is now ‘virtually impossible’. Is it right?

Last modified on Sat 3 Apr 2021 06.01 AEDT

Australia’s leading scientists made a significant global-scale declaration about the fight to deal with the climate crisis this week – but you could be forgiven if you missed it.

In what it described as a landmark report, the Australian Academy of Science painted a picture of what could happen to the country under 3C of global heating, including ecosystems made unrecognisable, food production being compromised and people’s ability to exist and survive in hotter and longer heatwaves regularly tested.

The central message? There is no time to wait.

But lying within the report was another substantial claim – that limiting global heating to 1.5C was now “virtually impossible”.

The 1.5C goal is a key global aspiration. It is inscribed in the Paris climate agreement and has been adopted by campaigners, governments and businesses leaders as the focus of efforts in the lead-up to climate summit in Glasgow this year.

That the body representing Australia’s scientific community had dismissed what has become an international benchmark was quickly noticed. By Thursday morning it had been translated into a front-page story in Nine newspapers that reported, if hope of 1.5C is gone, the Great Barrier Reef is “all but doomed”.

Some experts in the field reject the claim 1.5C is is effectively lost. They argue that the academy, in adopting a position that remains contested in the scientific community, has miscalculated and overreached.

The dispute is over complicated science – essentially, estimates of “carbon budgets”, which set out how much greenhouse gas can still be emitted. But it has ramifications that spill into the world of campaigning, where views differ on whether it is better to give people a message of hope about what can be achieved or to whack them with a story about what is inevitably gone.

Can we avoid 1.5C heating?

The academy sets out its calculation in its report. Under the heading “the emergency of immediate action”, it says the world has warmed by an average 1.1C since the late 1800s, and the amount the world can still emit if it is going to limit warming to 1.5C is between 40bn and 135bn tonnes of carbon.

It argues that this allows about only three or four more years of emissions at current levels, and makes a 1.5C target virtually impossible to achieve.

Some scientists disagree with this assessment. Dr Bill Hare, the chief executive and senior scientist with Climate Analytics and a longtime adviser to developing countries, says the calculations the academy relies on are at odds with other analyses by experts in emission pathways, which is a recognised scientific field.

He says they are also at odds with the UN’s intergovernmental panel on climate change, which was quoted in 2018 as saying 1.5C would be gone if there were 12 more years at the current rate of emissions.

Hare praises the rest of the academy report – “it’s really great in all other respects” – but says the claim 1.5C heating is “virtually impossible” to avoid is a “serious error”.

“I don’t think it is a scientific view, and it’s possibly based on a feeling it’s got too close for comfort,” he says. “I think it’s perhaps based on a misguided view that they think that saying this is going to wake people up.

“If you look at this in a very systematic way, we are still able to pull this off. The right conclusion is the 1.5C limit is really hanging in the balance, and I think everyone knows that, and that’s why we need to get on with really rapid action.”

Prof Piers Forster, director of the Priestley International Centre for Climate at the University of Leeds and a lead author of the 2018 IPCC report on the ramifications of a 1.5C target, agrees it is “too simplistic” to write off a 1.5C target.

He says the carbon budget used by the academy was based on estimates that relied on probabilities, and that is “not a good way of looking at this”. Forster argues that the scientific literature has not changed since the 2018 IPCC report found limiting heating to 1.5C was, in his words, “possible, but super-challenging”.

Dr Joeri Rogelj, from the Grantham Institute at Imperial College London and another senior author of the 2018 IPCC report, took to Twitter to express his concerns, saying that even if the chance of staying within 1.5C was less than 50% that did not qualify as virtually impossible.

He says the academy did not back up its statement in the evidence and analysis provided to support it, describing it as “an unfortunate miscommunication of uncertainties and risk”.

Prof Michael Mann, the director of the Earth System Science Center at Pennsylvania State University,

says the published evidence offers a simple conclusion – keeping global

heating to 1.5C would require global emissions to be cut in half over

the next decade. He says this is “entirely doable” and “simply a matter

of political willpower”. “There’s nothing about the physics that says it

isn’t [possible].”

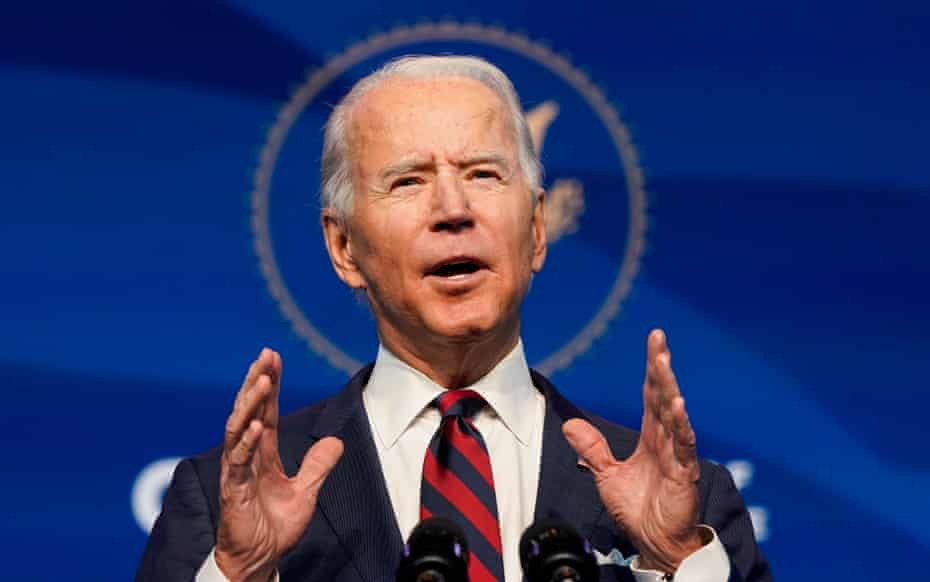

Mann sees cause for optimism in the US, where the new president, Joe Biden, this week confirmed the details of an extraordinary US$2tn infrastructure package that puts climate action at its centre. It includes $174bn to promote electric vehicles, $85bn for public transport, more than $200bn to modernise housing for people on low incomes and $100bn to upgrade the electricity network. He aims to phase out fossil fuels from the electricity grid within 15 years.

What’s the case for the ‘virtually impossible’ claim?

Several scientists suggested the contested section of the report was helmed by Prof Will Steffen, a respected climate scientist who ran the Australian National University Climate Change Institute and the international geosphere-biosphere programme in Stockholm. Steffen now works at the Climate Council, which plans to release its own report later this month on whether limiting heating to 1.5C is achievable. He was away this week and could not be reached before publication.

But the academy’s conclusion is strongly supported by Dr Glen Peters, a research director at Norway’s Centre for International Climate Research, who says it “should be applauded for being frank”.

Peters says while it is true there is scientific literature to support the idea that 1.5C is still possible, and there are plenty of people who argue it is “necessary to say 1.5C is possible to keep the hope alive”, it should not be ignored that countries are still building fossil fuel power plants with a lifespan of 50 years and that international aviation still has no clear route to becoming carbon free.

He says published science suggests even if the world cuts emissions in half by 2030 and hits net zero by 2050 there will still need to be a major program to remove CO2 from the atmosphere, to stabilise temperatures at a relatively safe level.

“The world is just nowhere near doing what is required for 1.5C,” Peters says. “Saying anything other than 1.5C is virtually impossible is irresponsible and misleading.”

Prof Lesley Hughes, a climate change ecologist, part of the panel who wrote the academy report and Steffen’s colleague at the Climate Council, says the latter body’s upcoming analysis on 1.5C heating will go into greater detail explaining how the “virtually impossible” assessment was reached. She says multiple lines of inquiry informed the conclusion that staying below that level is, in her words, “an extraordinary challenge”.

Hughes’ central point is that it is important to distinguish between the question of how much the temperature will rise under current estimates, and the question of what temperature targets the global community should be setting to avoid catastrophic damage. On the latter point she believes 1.5C remains an important goal but says the evidence suggests global temperatures will overshoot that mark, at least for a time.

On criticism of the academy’s use of the phrase “virtually impossible”, Hughes says: “We understand that anyone who has been working hard to alert the global community to the dangers of climate change will feel disheartened by the acknowledgement in the report that we are still a long way from solving the problem, but the academy report also outlines the real opportunities and benefits of moving rapidly to a decarbonised economy.”

Prof Mark Howden, director of ANU’s Institute for Climate Energy and Disaster Solutions, a vice-chair of the IPCC and an author of the academy report, says its finding on 1.5C is consistent with peer-reviewed evidence. He points to a February study in the journal Communications Earth & Environment that found most countries were not on track to meet the targets they had pledged under the Paris agreement, and the probability of keeping heating below even 2C was only 5%.

But he says he understands the argument that saying limiting heating to 1.5C is out of reach could take pressure off governments and that could “tend to increase the likelihood of temperature increases”.

Howden stresses that the Paris agreement goal of keeping temperatures well below 2C is still within reach, and suggests that reframing the language to “extremely difficult” instead of “virtually impossible” may have sent a clearer message about the need to strive to address the issue. “Just because something is extremely difficult it does not mean we shouldn’t try,” he says.

For its part, the academy says it stands by the evidence in the report, and adds: “The work of scientists is always open to challenge, analysis, discussion and debate.”

Is 1.5C the right question?

Several scientists stress that focusing too much on whether 1.5C heating can be avoided risks distracting from the ultimate goal of reining in the climate crisis as much as possible.

There is no doubt that, however you look at it, its impact will be much reduced if the temperature rise is limited to 1.5C. The Great Barrier Reef is a case in point. The IPCC’s report found coral reefs were likely to decline by between 70% and 90% if the temperature rise hit 1.5C. At 2C they are expected to decline by more than 99%.

But scientists say 1.5C should not be seen as a line at which the future is won or lost. There are scenarios under which 1.5C is passed but rapid action over the century allows average global temperatures to fall back below this level, in part through solutions that draw CO2 from the atmosphere. Equally, there are potential tipping points as ice and permafrost melt and forests recede that could increase the pace of warming.

History shows how quickly the world can move if countries put their mind to it. A decade ago, Forster says, the best projections suggested the world was looking at 3.5C to 4C by the end of the century, but an escalation in commitments has shifted that. “Today, if all current national targets are achieved we could be looking at something more like 2.1C of warming,” he says.

Mann says he is concerned focusing on absolute targets like 1.5C or 2C can divert from the bigger job. He offers the analogy of trying to get off a highway. If the world missed the 1.5C “exit ramp” that doesn’t mean it should not aim for the ramp at 1.6C. “And if we miss that, the 1.7C exit ramp,” he says.” Every tonne of carbon we don’t burn makes things better, reduces the harm and the risk.”

Peters offers a different analogy, one perhaps better suited to a sports-obsessed Australia. “Climate is not like a footy match where you lose and it is game over,” he says. “The climate game continues, so even if the 1.5C game is lost, it is still game-on for 1.6C and 1.7C. The critical point with the ‘virtually impossible’ framing is that it is clearly explained that there is still a lot worth fighting for.”

On this, Hughes says, everyone agrees. “The new mantra is that every fraction of a degree, every year and every choice matters.”

.png)

No comments:

Post a Comment