Extract from The Guardian

Ketan JoshiSeeing the span of our children’s lives laid over a climate projection graph slices through the boredom that comes with climate apathy

‘This is a unique moment of clarity for a field of scientific inquiry that has faced immense, unfathomable opposition over the past decade’ Photograph: Danny Lawson/PA

Contact author

Wednesday 7 June 2017 11.57 AEST Last modified on Wednesday 7 June 2017 12.23 AEST

Long after we each cease to exist, the physical outcomes of the choices we make today, and tomorrow, will linger. Shadows of our decisions on policy, energy and lifestyle will manifest as the consequence of our injection of greenhouse gases into the Earth’s atmosphere.

The forecasted outcomes of unchecked climate change are serious and long-lasting. Climate science regularly emits dire warnings and precipitous graphics illustrating dangerous changes to the oceans and atmosphere in the coming decades. They also fail, profoundly, to inspire widespread preventative action, partly because the future is distant and dim.

The fact that long-term warnings bounce off audiences is a zone of friction for science communication. There’s a lack of connection between the numbers drawn from climate science and the personal, immediate motivations required to drive active prioritisation of climate action.

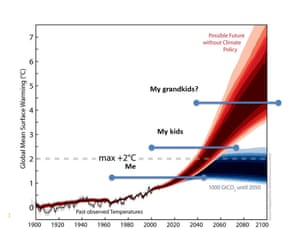

Recently, a tiny addition was made to a well-worn climate chart that stretched connective material between the empirical end of climate science and the raw, human, personal end:

The blue lines were added by the Climate Council’s Lesley Hughes (ANU climate scientist Sophie Lewis had a similar idea a few months back).

Hughes’ addition dislodges a distracted audience from the stickiness of information saturation. These looming decades don’t seem distant when we think about the simple fact that children we know today will still be alive, and they’ll need jobs, and food, and energy security and infrastructure. They’ll be balancing these priorities in a world badly damaged by the choices we make today around emissions reductions.

Per Espen Stoknes, a Norwegian psychologist, has examined why people continue to feel disconnected from climate warnings, despite the strength of the science. He says, “People think this is far off – it is not here and now, it’s also up there in the Arctic or Antarctica, it affects other people, not me, I’ll be old before this really happens, other people are responsible, not me. We distance ourselves from it in so many ways that the pure facts are not sufficient to generate a sustained sense of risk”.

What Per Espen Stoknes describes as the “climate paradox” – a seemingly inverse relationship between scientific information and climate concern – is born out in Australian polling data:

Climate concern v science acceptance

%

place climate as a top 3 priority

accept human causation in climate change

0

20

40

60

Nov 2009

Jun 2011

Jul 2013

Nov 2015

Feb 2017

The chart above shows the percentage of respondents who rate “addressing climate change” in their top three issues in deciding how to vote at a federal election. It also shows the percent of respondents who accept the scientifically-verified finding that humans are causing changes in the earth’s climate. Though acceptance of the science is at a record high, the number of people placing climate in their top three voting issues is trending downward.

Seeing the span of our descendant’s lives laid out over the physical consequences of our choices slices through the noise. It might help to push climate action upwards as a priority for Australians. The climate paradox looms large in America, too. Climate science acceptance is at a record high. Environment was third-lowest in priorities for the 2016 US election.

US President Donald Trump’s decision to withdraw from the Paris climate agreement has highlighted a shift within global climate advocacy. Climate change was absent from US media for most of 2016, but has dominated the news since Trump’s announcement. A growing collection of American cities have signed up to the Paris climate accords, in defiance of the federal decision. The European Union have cut the US government out of their negotiations, and will deal directly with states and businesses.

After years of climate boredom, a solid bolt of energy animates these affirmations, in stark contrast to weird, rambling stream of falsehoods in Trump’s announcement and the deeply hollow, awkward celebrations of climate change deniers.

Trump’s symbolic act was designed to signal his disdain for progressive obsessions and his care for American jobs. Instead, it has catalysed global resolve, been met with near-universal condemnation, refocused media coverage and distanced climate deniers.

This is a unique moment of clarity for a field of scientific inquiry that has faced immense, unfathomable opposition over the past decade. Climate doubt is in retreat. Climate science acceptance follows an inverse pattern, rising to record high levels. Climate scientists are working hard to humanise their messages, linking them to personal experience and the lives of the people who’ll inherit the consequences of today’s decisions. With luck, Trump might go down in the history as the man who catalysed a new era of climate action.

So this is the perfect time to string a conductive connection between the high-resolution picture of the future that’s been painted by intensely reviewed and re-reviewed scientific inquiry, and our responsibility to future inhabitants of the atmospheric stew into which we’re injecting gigatonnes of greenhouse gases.

Connecting numbers to feelings is the antidote to the curse of temporal distance feeding the climate communication paradox. This is a jarring reminder of the generational inequity we exploit and worsen when we choose to disavow responsibility for the machines and industries causing the problem.

No comments:

Post a Comment