Interview

At 85, Willie Nelson still spends half the year on the road and is

busy supporting Texan Democrat nominee Beto O’Rourke. And the giant of

country music’s 2,500 song catalogue just keeps growing

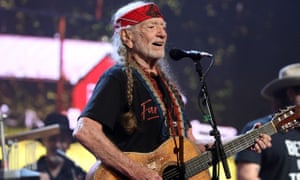

Nelson performs at Farm Aid, September 2018.

Photograph: Taylor Hill/Getty Images

In

the Boston suburb of Mansfield, Massachusetts, I am summoned to Willie

Nelson’s tour bus a couple of hours before he takes to the stage at the

Outlaw music festival. Meanwhile, in Dallas, the progressive Democrat Beto O’Rourke is wrapping up his first debate with Ted Cruz,

his Republican opponent in Texas’s too-close-to-call US Senate race.

O’Rourke will later be seen celebrating his strong performance by

air-drumming to the Who in a Whataburger drive-thru.

Soon after Nelson signed on to headline a major O’Rourke rally on 29 September, some conservative fans reportedly planned to boycott his music in protest. A doctored photograph went viral of Nelson in a Beto for Texas shirt, flipping off at the camera like his friend Johnny Cash. But an actual boycott appeared to be bogus, or at least overblown; and anyway, as singer Wheeler Walker Jr tweeted: “You can argue politics all you want, but you cannot argue Willie.”

A waxing harvest moon hovers over the latest incarnation of the Honeysuckle Rose, Nelson’s bus and home on the road. Annie D’Angelo Nelson, his fourth wife since 1991, greets me warmly. “Were you watching?” she asks, meaning the debate. “I thought Beto blew him away.” She is the dynamite to Willie’s calm when he ambles into the kitchen, his grey hair in two long braids. At 85, Nelson is still vigorously hale, as handsomely and admirably weathered as his battered guitar, Trigger. “Willie, you gotta look at her butt!” Annie says – my jeans are embroidered with a map of Texas. From the pocket I pull a “You Beto Vote For Beto!” sticker I picked up in Austin.

Settling into the dinette where he regularly hosts guests, Nelson is an intensely receptive listener, eyes twinkling when he lets out full-lung laughter, but never straying. You can see why he tends to win his legendary dominoes and poker games.

At Nelson’s annual Fourth of July picnic, O’Rourke, who played in punk bands growing up in El Paso, and who referenced the Clash in his Cruz debate, joined Willie onstage for It’s All Going to Pot and Will the Circle Be Unbroken. “We hit it off immediately ’cause he’s a musician too. He’s for the same things I’m for in Texas, which is letting everybody do what they want to,” Nelson says. He levels his steady gaze. “Ev-er-y-body.”

Soon after Nelson signed on to headline a major O’Rourke rally on 29 September, some conservative fans reportedly planned to boycott his music in protest. A doctored photograph went viral of Nelson in a Beto for Texas shirt, flipping off at the camera like his friend Johnny Cash. But an actual boycott appeared to be bogus, or at least overblown; and anyway, as singer Wheeler Walker Jr tweeted: “You can argue politics all you want, but you cannot argue Willie.”

A waxing harvest moon hovers over the latest incarnation of the Honeysuckle Rose, Nelson’s bus and home on the road. Annie D’Angelo Nelson, his fourth wife since 1991, greets me warmly. “Were you watching?” she asks, meaning the debate. “I thought Beto blew him away.” She is the dynamite to Willie’s calm when he ambles into the kitchen, his grey hair in two long braids. At 85, Nelson is still vigorously hale, as handsomely and admirably weathered as his battered guitar, Trigger. “Willie, you gotta look at her butt!” Annie says – my jeans are embroidered with a map of Texas. From the pocket I pull a “You Beto Vote For Beto!” sticker I picked up in Austin.

Settling into the dinette where he regularly hosts guests, Nelson is an intensely receptive listener, eyes twinkling when he lets out full-lung laughter, but never straying. You can see why he tends to win his legendary dominoes and poker games.

At Nelson’s annual Fourth of July picnic, O’Rourke, who played in punk bands growing up in El Paso, and who referenced the Clash in his Cruz debate, joined Willie onstage for It’s All Going to Pot and Will the Circle Be Unbroken. “We hit it off immediately ’cause he’s a musician too. He’s for the same things I’m for in Texas, which is letting everybody do what they want to,” Nelson says. He levels his steady gaze. “Ev-er-y-body.”

Texas looms large in all his music; in concert, his songs sound as if they were scripted to fill its enormous skies. “I miss it all the time,” Nelson says. “I miss the hot weather, I miss the cold weather, I have some ponies down there I like to see.” Nelson used to average 200 days a year on the road, now around 150; it’s his preferred way of being. His sister, Bobbie, the longtime pianist in Nelson’s Family band, says Nelson takes after their mother, a wanderer who left her and Willie with their grandparents when they were very young. The road gives him a rare vantage point; he has seen more of the US, and more of its changes, than most. He takes this in his stride. “I’ve moved around a lot in 85 years,” he says. “And I went through a lot of political spaces in our country – four years of this, eight years of that.”

Collective memory recalls Nelson allegedly getting high on the White House roof during his friend Jimmy Carter’s administration, but tends to forget Nelson’s long history of political involvement. Over the years he has lent his support to friends such as the irrepressible Texas governor Ann Richards, the satirist Kinky Friedman, even the independent presidential candidate Ross Perot. He supported Barack Obama and both Bernie Sanders and Hillary Clinton. He has spoken out against LGBTQ discrimination and covered the Ned Sublette song Cowboys Are Frequently, Secretly Fond of Each Other. “I call myself a VI,” Nelson says. “Very independent.”

Without deigning to mention Trump by name, Nelson included the protest song Delete and Fast Forward, on God’s Problem Child in 2017, in apparent opposition to the president’s agenda of hate and divisiveness. Nelson was outraged by the detention centres and the forced separation of families: “I thought everything that happened there was unforgivable.” He opposes the proposed wall, too. “We have a statue that says: ‘Y’all come in,’” he says. “I don’t believe in closing the border. Open them suckers up!” When I ask how his 33-year-old charity Farm Aid supports immigrant farmworkers in the US, he is reflective. “We need those folks,” Nelson says. “I used to pick cotton and pull corn and bale hay and I’m lucky to play guitar now, but we have to have the people who want to work, and take care of them.”

Nelson has always been a VI artist, too. In 1978, on the heels of the masterful narrative Red-Headed Stranger, the gospel album The Troublemaker, and the conceptual Phases and Stages, the studio worried it had been a while since his outlaw hit Shotgun Willie and insisted audiences wanted more “edgy cowboy songs”. But Nelson ignored them – “I listened to my heart,” he wrote – and recorded an album of forgotten standards, the Kurt Weill and George Gershwin numbers he and his sister Bobbie learned as kids in Abbott, Texas, songs that helped form their musical telepathy.

Stardust, with Nelson’s searing covers of All of Me and Blue Skies, went platinum and earned a Grammy for Georgia On My Mind. My Way, Nelson’s 68th studio album and his second this year, with covers of Sinatra standards, is the latest chapter in Nelson’s singular interpretation of the Great American Songbook and a tribute to his longtime favourite singer. “Sinatra’ll lay down behind the beat and he’ll speed up and get in front of the beat,” Nelson says, “and I thought that was cool. I tried mimicking it a little and I wound up doing that a lot in my songs.”

He and Sinatra cemented their mutual admiration with a duet of My Way in 1993. “We used to play shows together in Vegas and Palm Springs,” Nelson remembers. After one gig, Sinatra invited Nelson to his place in Palm Springs. “I was in a big hurry to go somewhere, so I said, ‘I’ll catch you next time,’ and I never did see him again,” Nelson says. Sinatra died of a heart attack in 1998. “I always regretted that.”

I repeat something Kinky Friedman said of him: “Willie walks through the raw poetry of time.” Nelson has written some 2,500 songs, and numerous books, including two memoirs, but there is a part of him that remains unspoken and essentially mysterious, perhaps even to himself. Early on, he wrote three of his best songs – Crazy, Funny How Time Slips Away and Night Life – in the span of a week; even in anthems such as Whiskey River there is pure and stealthy lyricism, songs that understand their listeners better than they can articulate. Does Nelson even know, I wonder, where some of his deepest words come from?

Not really, he admits. “You know, every song I write that I’m proud of, I wonder how it got there. I think the same thing about Merle’s songs and Hank Williams. I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry: what was Hank going through when he wrote that? He died when he was 29 – compared to him, I haven’t had a lot of rough times at all.”

But he has been through a mighty lot, I venture, thinking of the absence of his mother, of an often hard-lived life, of the loss of his son Billy to suicide in 1991. “I think there’s some things that can only come out in songs,” Nelson agrees. “You can write a beautiful book, but take verses out of it and put a melody to it and you’ve got another dimension.

“I wrote something the other day that said, ‘I don’t want to write another song, but tell that to my mind!’” he continues, laughing. “‘I just throw them out there and try to make them rhyme.’ I write everywhere, anywhere. I write a lot at home at night.”

“It’s like birthing babies!” Annie says from one of the bus’s built-in sofas. She doesn’t mind; in fact, she stays up listening.

He thinks in lyrics first; the music comes after. “Usually it starts as a poem,” he says. “At some point I’ll get up and go get the guitar and see what kind of melody those words suggest.” A song, he reckons, is just a poem with a melody. I say I’ve always thought that words and melody just naturally found each other in his songs. “Good!” Nelson says. “Fooled ’em again!”

As the Family convenes onstage, dust shines up in the spotlights and a musky cloud wafts up from the front row to meet it. Under the lights, Trigger’s moonfaced complexion is visibly cratered where Nelson has dug into the wood. The crowd is a smoky sea of grizzled grandpas, grandmas in Dwight Yoakam shirts, teenagers whose uncles played them Nelson, people on dates, people in wheelchairs and people who look like they might have just come from the rodeo down the street. Like Nelson says: “There are no political debates in my audiences.” When he and the Family play Roll Me Up and Smoke Me When I Die, it is at once pro-weed anthem and as gospel as Hank’s I Saw the Light. Nelson is the poet laureate of the guy in the parking lot; the girl, too.

At last when the house lights go up, a roadie gathers a bunch of rose petals scattered on the stage and tosses them unceremoniously in the direction of a few stragglers. “I don’t want it to be over!” says a veterinarian near me, eyes shining. “Willie’s even better than he was 10 years ago.” Her friend confesses she missed that concert – the last performance she saw here was the Spice Girls, 20 years ago – but in the meantime she has converted to Willie too. “We’re farm girls from Mansfield,” she says, reluctantly following the crowd out of the amphitheatre. The vet glances back at the emptying stage, and as Nelson has just done for us in song, voices the thing we are all thinking inside. “He’s the last of them,” she says. “The last of the real ones.”

My Way by Willie Nelson is out now on Legacy Recordings

No comments:

Post a Comment