Extract from The Guardian

At a Toowoomba crime forum last week, residents told harrowing stories of pensioners being mugged at ATMs, youths roaming the streets with machetes and children too scared to leave home.

Community outrage in the face of these kinds of shocking crimes is very real and very understandable. The anger is turbo-charged by media reports that teenage burglars and car thieves are boasting about their exploits on social media, magnifying the anguish felt by victims and their families.

What matters, though, is creating solutions that work. Unfortunately for the “lock-’em-up-and-throw-away-the-key” advocates, detention is the worst possible environment for effective rehabilitation.

The most recently available crime data suggests there has been a steady decline in the size of the youth offender population across Australia, including Queensland, for the past 15-20 years. Community concern is not misplaced, however, because a minority of about one in 10 offenders are committing more and more serious, violent offences – so many in fact that they account for about half of all youth crime.

The real problem is this minority of early onset, persistent, serious youth offenders. What we know from scientific research about these young people is that they are much more likely than non-offending young people to have suffered serious trauma while growing up, including adverse childhood events such as emotional, physical or sexual abuse, all kinds of neglect and lack of supervision, household substance abuse or mental illness, and having a parent in prison.

Incarceration does not, contrary to political rhetoric, deter or rehabilitate these traumatised young people or their peers. What it does do, however, is very effectively re-traumatise them by exposing them to violence that they witness or encounter in detention.

Detention, including the detention of young people in remand, produces higher rates of rearrest and reincarceration than community-based alternatives. In Queensland nearly 90% of children in detention are unsentenced. Studies in the US show that even after controlling for the effects of offending history and other key risk factors, pre-trial detention more than triples the likelihood that these young people will be imprisoned again, after their court adjudication.

To turn around the lives of serious repeat offenders and truly make communities safer, we have to deal with the causes of their offending. Getting serious about stopping serious repeat youth offenders means helping them to develop “psychosocial maturity” – which includes the skills to control their impulses (such as lashing out in anger when someone bullies or provokes them), weigh the consequences of their actions, consider others’ perspectives, delay gratification, and resist pressure from peers (Hey, let’s have a blast and steal a car tonight!).

The fundamental problem with youth incarceration as a crime policy is that it impedes young people’s ability to mature psychologically and participate in mainstream society.

As the US-based Sentencing Project’s latest review of the scientific evidence on the effects of youth incarceration states: “The purported solution (incarceration) does not address the underlying cause of the conduct (immaturity).” On the contrary, incarceration limits opportunities to gain a school qualification, acquire job skills, and live a healthy life physically and mentally.

What I have referred to as the political “Punch and Judy Show” or the “Law and Order Auction”, where politicians from both sides outbid each other to portray themselves as “tougher on youth crime”, is actually making the community less safe. The pantomime of the nightly news must give way to a bipartisan commitment to evidence-based youth crime policies, in partnership with and controlled by the most affected communities, particularly First Nations communities.

The emphasis should be on good science, primary prevention, and early intervention, with substantial investment in community mobilisation strategies such as Communities That Care, which, in Australia and around the world, has been proven to reduce youth crime and promote positive youth development at the whole-of-community level.

These types of interventions can divert children showing problematic behaviours at a young age, preventing a lifetime of needless suffering and community trauma.

Frustrated communities have every right to demand solutions. But they should be demanding solutions that work.

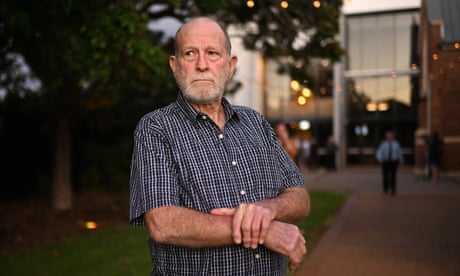

Ross Homel is an emeritus professor in criminology and criminal justice at Griffith University, and was awarded an Order of Australia honour in 2008 for services to education through research into the causes of crime, early intervention and prevention.

No comments:

Post a Comment