Extract from The Guardian

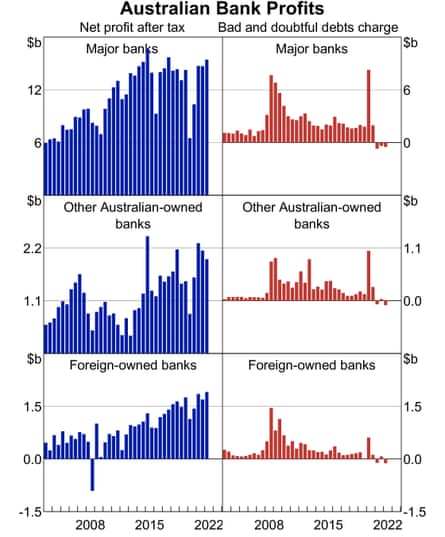

After being told to expect stable interest rates until at least 2024, mortgage borrowers have been hit with a string of increases in the Reserve Bank cash rate, rapidly passed on by the banks. A small reduction in the Commonwealth’s margin between deposit rates and lending rates was not enough to prevent a 9% increase in profits.

But is this just griping about a necessary part of our economic and social system? Are the banks, and the financial sector as a whole, making a contribution that justifies their handsome profits and the high salaries paid to executives?

The Australian Treasury certainly thinks so. In a 2016 report on the then-booming “fintech” sector, Treasury said it was the largest contributor to the national economy, adding about $140bn to the nation’s GDP over the last year. It has been a major driver of economic growth and considering it employs 450,000 people, it will continue to be a core sector of the economy in the future.

Recent failures of Buy Now, Pay Later services have taken some of the sheen off fintech, but there is no sign of a change in the view that the $140bn spent on financial services is good value for money.

Retail customers might well disagree. The last really big innovation provided by the banking sector was the introduction of credit cards in the 1970s. Most subsequent innovations (foreign currency loans, honeymoon rates, BNPL) have been little better than confidence tricks, leading people to take on more debt that they can afford, with the true costs hidden from view. Of course, there have been big technological changes resulting from the rise of the internet, but the cost savings from these changes haven’t flowed through to consumers.

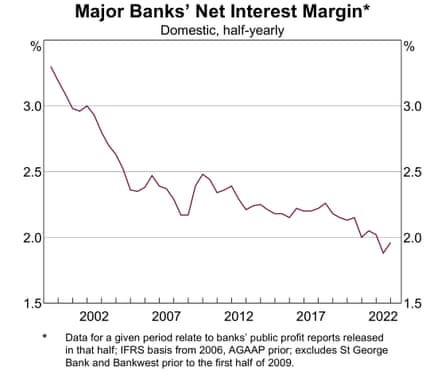

Bank margins have fallen somewhat over the past 20 years, as can be seen in the Reserve Bank’s own chart. But expressing the margin in percentage point terms obscures the fact that the size of the average mortgage has increased much faster than average wages or prices in general, which determine most of the banks’ operating costs.

The margin does include an allowance for bad debts, which would be expected to grow in line with the total amount of debt outstanding. But the banks’ losses from bad debts are tiny in relation to their profit margins and are almost entirely associated with business failures in periods of economic crisis. The rate of foreclosures and mortgage repossessions is tiny – as low as 0.1% of all loans in most years.

But while mortgage and deposit rates are what concern most of us directly, the central claim made in support of our massive financial sector is that, thanks to the deregulation of the 1970s and 1980s, the financial sector has been a major driver of economic growth. According to the claims made in support of deregulation, a dynamic financial sector will increase both the rate of business investment and the efficiency with which investment is allocated.

A central implication, which has formed the basis of public policy for the last three decades is that governments should get out of the business of capital investment and ownership. This claim has motivated privatisation, public-private partnership and the perceived urgency of reducing gross public debt.

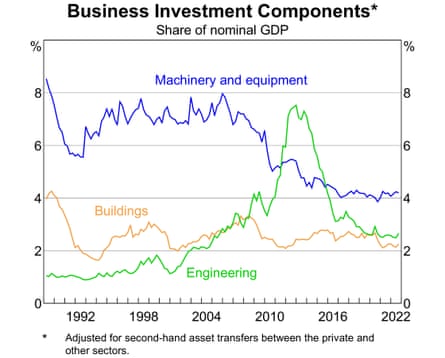

Sadly, there is little evidence to support this claim in Australia, or elsewhere in the world. With the exception of a brief spike in engineering investment during the mining boom, business investment has been declining steadily since the advent of financial deregulation.

There is no evidence that the allocation of investment capital has improved. The much-touted “productivity miracle” of the 1990s disappeared long ago. According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, capital productivity has actually fallen, declining by 20% since 1995. It is only the steadily declining price of (almost entirely imported) computing and communications technology that has prevented even poorer economic performance.

It is one thing to point out that the financial sector is not contributing as much to the Australian economy as it takes out. Unfortunately, it’s quite another to fix the problems, enmeshed as we are in a dysfunctional global financial economy. At a minimum, though, it’s time to recognise the financial sector as a drag on our economic and social welfare, rather than as a source of economic dynamism and policy guidance. Policies that reduce its size and profitability are more likely to be beneficial than otherwise.

No comments:

Post a Comment