Exclusive: Western Australian police data shows family violence a big concern in Wyndham and Kununurra, despite card’s introduction

The cashless debit card has failed to reduce family violence in one of the first trial sites and may have actually coincided with an increase in abuse, police data released under freedom of information laws suggests.

New figures obtained by the Australian National University researcher Elise Klein add more weight to critics’ claims that the card has not reduced reports of family violence about three years after welfare recipients were placed on to the card.

Western Australia police data released under FOI laws in 2018 had shown family violence-related assaults and police attendances in the East Kimberley communities of Wyndham and Kununurra rose after the card was introduced in April 2016.

“There are some questions about the data but it does still show it’s definitely not decreasing … and there is some increase,” Klein, who has studied the card’s impact in the Kimberley, told Guardian Australia.New figures obtained by the Australian National University researcher Elise Klein add more weight to critics’ claims that the card has not reduced reports of family violence about three years after welfare recipients were placed on to the card.

Western Australia police data released under FOI laws in 2018 had shown family violence-related assaults and police attendances in the East Kimberley communities of Wyndham and Kununurra rose after the card was introduced in April 2016.

“You can look at those numbers and say, something’s up here,” she added.

While she did not view the card as a “causal factor” for family violence, she said it was “an added factor of stress and hardship in families which may then lead to violence”.

“They [the government] should be researching this area and not proposing extending the cashless debit card until we know what’s happening more clearly,” Klein said, describing the proposal as “shameful”.

However, treating the data separately, the figures show that post July 2017 to April 2019, there has been no clear reduction in serious family assaults and general family assaults.

It follows a clear increase in family violence assaults in the pre-July 2017 data, which appears to begin when the card was introduced in the East Kimberley.

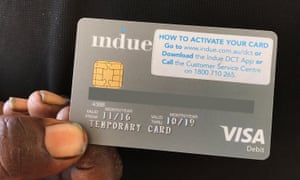

It comes as the government pushes for a nationwide rollout of the controversial policy, which quarantines 80% of a person’s welfare payments on to a card that cannot be used to withdraw cash or buy certain prohibited items.

The government is currently seeking to win support from the independent senator Jacqui Lambie to expand the card into the Northern Territory. Welfare recipients in the NT were placed on a similar form of income management, known as the Basics Card, during the Intervention.

“I myself have noticed the increase in youth crime, domestic violence, drinking, smoking, drugs, anxiety and depression, no wraparound services as promised,” she said.

“It is not making things any better,” Walley added. “It is not slowing down the alcohol intake and drug taking. They find a way around it.”

Guardian Australia has previously reported concerns about the card and its potential effect on domestic violence survivors. One woman, Jocelyn Wighton, from Ceduna, South Australia, told an event in 2018 she would not have been able to escape her abusive marriage under the income management scheme.

A spokeswoman for the social services minister, Anne Ruston, said the government had heavily invested in domestic violence programs, including specific support and prevention strategies for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities.

“The causes of domestic violence are complex and varied,” she said. “Evidence indicates Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women and children continue to experience disproportionally high rates of violence.”

The spokeswoman added the government had commissioned the University of Adelaide to undertake an evaluation of the cashless debit card trial sites.

“We expect results from three of the sites to be available in the first half of this year,” she said.

“The fact that reported [family violence] incidents have increased indicates a greater willingness for vulnerable/reluctant victims to report these incidents, thus allowing the police and other agencies to help break the FV cycle and support our most vulnerable members of community,” she said.

“In recent times within the Kimberley, police have certainly been pro-active in attempting to speak with persons and raise awareness in respect to FV, including strengthening relationships and giving victims the courage to report any incidents.”

In 2017, the Kimberley district police superintendent Allan Adams told a Senate inquiry there was a “lack of evidence to support the belief that the introduction of the cashless debit card has contributed to an increase in crime in Kununurra”.

However figures provided by WA police to state parliament in 2017 showed 277 theft offences in Kununurra in the year to May, up from 195 in the year leading up to the card’s introduction. Property offences and incidents of threatening behaviour and non-aggravated robbery also increased.

Lawford Benning, chair of the MG Corporation and an initial supporter of the card, told Guardian Australia in 2017 he had withdrawn his endorsement of the policy.

No comments:

Post a Comment