The myth of benign, peaceful settlement persists today – even as historians reveal a far more sinister picture

by Paul Daley

by Paul Daley

A friend sent me a photograph he’d taken in north-west Queensland

of the memorial to the Kalkadoon warriors who, in 1884, fought what was

perhaps the biggest battle against government forces to unfold on this

continent.

Local oral history, black and white, has it that dozens of Indigenous fighters were shot dead after they charged native police contingents under the command of Sub-Inspector FC Urquhart at Battle Mountain, about 60km from Cloncurry.

My friend’s photograph of the monument, featuring the face of a warrior, arrived at the tail end of a protracted period of outrage from politicians about the vandalism of public statues of colonial English fellows, James Cook and Lachlan Macquarie, who were both responsible for extreme violence against Australia’s Indigenes.

These were “cowardly, criminal” acts, we were told. As the rhetoric of indignation boiled over, the then prime minister even labelled the vandalism a “deeply disturbing act of Stalinism”.

But beyond the objections of local blackfellas who are conversant with the Battle Mountain conflict’s critical place in the pantheon of Indigenous continental resistance, equivalent opprobrium never greets the regular desecration of that memorial on the Mount Isa-Cloncurry Road.

Local oral history, black and white, has it that dozens of Indigenous fighters were shot dead after they charged native police contingents under the command of Sub-Inspector FC Urquhart at Battle Mountain, about 60km from Cloncurry.

My friend’s photograph of the monument, featuring the face of a warrior, arrived at the tail end of a protracted period of outrage from politicians about the vandalism of public statues of colonial English fellows, James Cook and Lachlan Macquarie, who were both responsible for extreme violence against Australia’s Indigenes.

These were “cowardly, criminal” acts, we were told. As the rhetoric of indignation boiled over, the then prime minister even labelled the vandalism a “deeply disturbing act of Stalinism”.

But beyond the objections of local blackfellas who are conversant with the Battle Mountain conflict’s critical place in the pantheon of Indigenous continental resistance, equivalent opprobrium never greets the regular desecration of that memorial on the Mount Isa-Cloncurry Road.

One, it seems to me at least, is more Stalinist. Not to mention colonially consistent. Quite like the manner by which Australia has told itself the history of the violent colonial and post-federation frontier – a story that, for 200-plus years, has had as ballast a trope of benign continental European settlement featuring benevolent, enlightened governors, understanding and compassionate settlers and Indigenous people who just “died off” or somehow wandered into near extinction.

A critical part of this trope (the progeny at best, of an acute historical narcolepsy and at worst, wilful national ignorance) has been the efforts of our earliest myth makers to diminish the numbers of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who were killed defending their lands or otherwise murdered, with cordite and lead, cold steel, poison, sickness and deprivation born of war.

The Australian Museum estimates that pre-European invasion in 1788, about 750,000 Indigenous people (representing some 700 language groups) inhabited the continent that would become Australia. This figure may well be an underestimate.

"The wars that raged across this continent claimed more Indigenous lives than the 62,000 Australian soldiers who died in the first world war"

Little over a century later, by federation in 1901, the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island population had diminished to some 117,000. Black-white warfare and organised massacres, no matter how you define them, with police, British soldiers, native police, militia and raiding parties as the perpetrators, accounted for many tens of thousands of deaths. Individual acts of violence – including shootings, poisonings, torture and illegal incarceration – killed many more. Battle wounds, starvation (owing to the depletion of traditional hunting grounds) and disease – all of which can also be directly linked to invasion and frontier conflict – killed countless others.

Yet the historiographic confect of benign, peaceful settlement and the unexplained “passing” or “extinction” of the “natives” pervaded well into the 1960s, replete with the deception that very few Aboriginal people died violently during pastoral and urban expansion and dispossession. Things began to change with the emergence of a new, more inquisitive, less empire-centric cohort of historians and writers who, not content with the Anglophile colonial trope of terra nullius and benevolence to the Indigenes, began to commit truth to the page.

Stanner declared:

"It is a structural matter, a view from a window which has been carefully placed to exclude a whole quadrant of the landscape. What may well have begun as a simple forgetting of other possible views turned, under habit and over time, into something like a cult of forgetfulness practised on a national scale."

As the historian Anna Clark points out, Stanner’s words acted as something of a propellant, if not a challenge – to a nation and its history writers.

She writes:

"His lectures profoundly influenced historians partly because of the image he captured: for a practice based on documentation, archiving and storytelling, silence is a compelling idea. And a whole-scale silence … indicated a bold reimagining of a national historiography on Stanner’s part."

Truth telling about frontier violence, including the stories of dozens of massacres that killed hundreds of Aboriginal people, was happening pre-Stanner. But its proponents were mostly lone voices who were often denigrated or marginalised – they included the Danish journalist and environmentalist Carl Feilberg, who took on (to his detriment) colonial Queensland over its mass killings of first inhabitants.

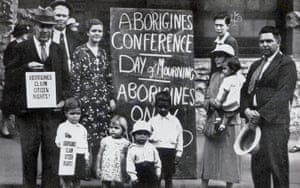

"The 26th January, 1938, is not a day of rejoicing for Australia’s Aborigines. It is a day of mourning. This festival of 150 years’ so-called ‘progress’ in Australia commemorates also 150 years of misery and degradation imposed upon the original native inhabitants by the white invaders of this country."

In the 1920s Anthony Martin Fernando, an Aboriginal man, protested widely in Europe, including in front of Australia House on the Strand in London, against the violence inflicted on his Indigenous brothers and sisters.

And there was also Douglas Grant, the Indigenous massacre survivor who served the empire in the first world war and afterwards argued vociferously for Aboriginal rights in the wake of the 1928 Coniston massacre, while his experience was already being unfairly written along the lines of that of another famous black man, Bennelong, as the tragic morality tale of a racial outcast who fell between the cracks of two worlds.

Anna Clark points out there is no clear seam in historiography to chart a precise segue from the “great Australian silence” to historical truth telling. She quotes the esteemed scholar Ann Curthoys, who has written extensively about Stanner: “There is neither complete silence before 1968, nor was it completely ended afterwards.”

In the 1970s and 1980s a number of historians – among them Henry Reynolds, Marilyn Lake and Richard Broome – began focusing on frontier violence, using the colonial records, newspaper archives and family histories (including generational oral accounts of killings).

Reynolds is acknowledged as the first Australian historian to make a calculated continental estimate of the number of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders who died violently in Australian frontier conflict. In his 1981 book, The Other Side of the Frontier, and after at least a decade’s research Reynolds estimated the figure at about 20,000.

It’s a figure I’ve referenced numerous times since about 2010 when writing about frontier history, and one that was for decades roundly – but unfairly – condemned by some reactionaries and historians of the right as a gross inflation. But subsequent scholarship, not least by the Queenslanders Raymond Evans and Robert Ørsted-Jensen, has rendered Reynolds’ figure conservative, perhaps by a multiple of three or four – or, if deaths attributable to disease and deprivation are included, by many times more.

It’s instructive speaking today to Reynolds – who is, to my mind, the living Australian historian who has done the most to uncover and highlight white Australia’s violent foundations – about his early research and how he arrived at the 20,000 figure.

He explains how he began researching The Other Side of the Frontier in 1970, while teaching at James Cook University in north Queensland. He began with local sources (the university then had no library to speak of), primarily the archive of the Port Denison Times of 1863 in the newspaper offices at Bowen.

“Once I began to immerse [myself] in the primary sources, such as newspapers, the nature and extent of the violence against Aborigines was inescapable,” Reynolds recalls. “I published my first piece based on that research in 1972 in Meanjin. It was titled Violence, the Aboriginals, and the Australian Historian.”

In Meanjin he wrote:

"White memories of racial violence have more often been expunged than preserved, while the decimating impact of disease and deprivation has often been accepted as a comprehensive explanation of a rapidly declining indigenous population. There is a very old belief that settlement was uniquely peaceful which can be traced back to the earliest writing on Australian colonisation."

Reynolds wrote that he believed “many more Aboriginals died in clashes with the settlers than the 1,000 to 2,000 who fell in the [New Zealand] Māori wars” and that in Queensland alone “I would think that 5,000 would be a conservative estimate”.

Another decade of work led to The Other Side of the Frontier, 10 years in which Reynolds “nationalised” his research, “looking all over Australia at Indigenous frontier conflict deaths, researching in every relevant public library and state archive, including the colonial records. I also researched at the British Library and the Royal Commonwealth Society in London. During that period I read almost everything conceivable that was available in the archives and the newspapers ...

“I felt it incumbent, as somebody who’d done research of such scope and breadth, to make some sort of public assessment of the number of Indigenous deaths in frontier conflict continent-wide. I also, in researching the book, counted all of the Europeans who were killed.

“My research led me to propose that the number killed was at least 20,000 Aborigines. At the time I felt that it was risky to put a figure on it because I anticipated that others – historians, but particularly the culture warriors – would heavily criticise me for that. I thought it was going out on a limb. But that is the conclusion I arrived at and that is what I published.

“Of course, in the decades since then, a number of others have done significant research on the numbers, utilising new archival material and other information and it is obvious that the figure of 20,000 is no longer adequate. It must be more. The figure must be significantly higher.”

Reynolds speaks of the significance of Evans and Ørsted-Jensen’s research on the numbers of killings in colonial Queensland.

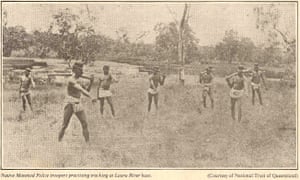

Based on an extrapolation of native police documentation, they estimated (conservatively) that as many as 60,000 Aboriginal people died in frontier violence in Queensland alone.

The national implications of the figure are profound; the wars that raged across this continent from 1788 did, it seem, claim more Indigenous lives than 62,000 Australian service personnel who died in the first world war.

Evans says their figure “has been assessed from the fullest spread of the data and a very careful, reductive reading of existing casualty figures”.

“The average death rate for native police attacks is around 11 and for private settler assaults around nine, making both fall well within the ambit of what is presently considered as a ‘massacre’ – but there were thousands of such ‘dispersals’ in Queensland alone.”

Ørsted-Jensen says the “higher level of violence in Queensland is, in our opinion, due solely to comparatively higher numbers of Indigenous people and tribes in that colony”.

“Yet probably Queensland is the only state which can provide material useful for the calculation of casualty estimates, the reason being that Queensland ran a government-funded force for 50 years, leaving us a small yet significant sequential series of records of conflict per police patrol.”

Ørsted-Jensen and Evans agree that, based on their Queensland calculations, “nationally the Australian frontier conflict during the 19th and into the early decades of the 20th century inflicted a death toll on Indigenous people probably no less than 100,000”.

Evans says: “Coincidentally, this figure is very close to the total death rate for Australian troops in all foreign military engagements combined.

"It appears the condemned were forced to gather wood for their own immolation"

Ørsted-Jensen points out that it “equates to 12% of the now commonly accepted pre-contact population estimates of 850,000”.

Reynolds says: “One has to take very seriously this great expansion of the accepted Aboriginal death rate in Queensland, based on the findings of Robert and Ray, given that the native police were roaming the countryside up there for 50 years ... remembering, however, that Queensland is quite unique in some ways because it is a place where settlers were given self-government, away from imperial restraint, when such a huge area of the territory was still in Aboriginal hands.”

He points out that official Australian commemoration for those who died in service in foreign wars includes many thousands killed as a result of disease and accident. By implication, he says, the official estimates of Indigenous deaths in the frontier wars should include the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people who died from indirect consequences of conflict such as disease and hunger.

This, potentially, adds many more thousands to even the most conservative estimates of Indigenous people killed in frontier conflicts.

Reynolds, now 81, also praises the importance of the writings about the Queensland frontier by the historians Timothy Bottoms – especially his book Conspiracy of Silence – and Jonathan Richards in The Secret War. He also highlights the contributions of a number of Western Australian academics, not least Chris Owen, whose book, Every Mother’s Son Is Guilty: Policing the Kimberley Frontier of Western Australia 1882 – 1905, methodically details the extreme violence, the political cover-ups and the complicity in murder of leading WA pioneering families including the Durack pastoral dynasty, who were lionised by the novelist Mary Durack in her Kings in Grass Castles and Sons in the Saddle books.

“The large and diverse Aboriginal groups of the Kimberley still refer to the colonisation period from the early 1880s right through to the 1920s as ‘the killing times’,” Owen says.

“This is because colonist and police killings were commonplace (as a tacitly accepted way of pacifying the largely lawless frontier) and often included incineration [for which] it appears the condemned were forced to gather wood for their own immolation. All to obliterate evidence that an Aboriginal body, that is a person, ever existed.

“Many of the killings were large-scale in what were called punitive expeditions, shooting Aboriginal people on sight after a colonist or prize stock had been killed. Notable recorded massacres followed the killing of miner Fred Marriot in July 1886, pastoralist John Durack in October 1886, George Barnett in July 1888, George Why at Mowla Bluff in 1916 and Fred Hay in the 1926 Forrest River massacre.

“However most of the killing was smaller scale (twos and threes) simply to remove Aboriginal people, usually the senior males, from the presence of cattle or to obtain Aboriginal women.”

Owen recounts the notorious cruelty of some Kimberley pioneering colonists, including Jack Carey, who, between 1919 and 1924, “threatened most Aboriginal people he met” and “shot and burnt large numbers of men, women and even children”.

“There appeared no limit to his pettiness. Carey once shot three Indigenous stockmen dead because they had left the goat yard gate open.”

No comments:

Post a Comment