We used to have a thriving domestic sector. After this crisis, Australia should have one again

In a speech on Monday,

Labor leader Anthony Albanese called for Australia to build up its

domestic manufacturing capacity in the wake of the pandemic. Hallelujah –

Australia could not be more ready for it.

Shockwaves from coronavirus’ comet-like impact on the world economy have shattered the neoliberal assumptions of 40 years of economic policy in many directions, but staring at the rubble remaining from what used to be a thriving local manufacturing sector is one of its most confronting exposures.

For four decades, manufacturing in the English-speaking west has shrunk. A combination of policy wilfulness and carelessness allowed a four-decade erosion rooted in two orthodoxies. First, that localised misery of factory closures was an acceptable trade-off for the lower prices of cheaper imports. Second, that globalised trade made the world more safe. There isn’t a business student in Australia who hasn’t been taught the conventional wisdom of the post-second world war experience that globalised trade brings globalised peace.

The problem with smashing components of an economy to ensure one kind

of safety is that you can leave yourself directly exposed to face a

different kind of threat. Long international supply chains and trade

dependence are vulnerabilities in a world where pandemics demand an

instant supply of masks

and ventilators, not to mention the practical realities of closed

borders, immediate travel bans, “contact and trace” policy and the

struggle of sovereign governments to contain contagions.Shockwaves from coronavirus’ comet-like impact on the world economy have shattered the neoliberal assumptions of 40 years of economic policy in many directions, but staring at the rubble remaining from what used to be a thriving local manufacturing sector is one of its most confronting exposures.

For four decades, manufacturing in the English-speaking west has shrunk. A combination of policy wilfulness and carelessness allowed a four-decade erosion rooted in two orthodoxies. First, that localised misery of factory closures was an acceptable trade-off for the lower prices of cheaper imports. Second, that globalised trade made the world more safe. There isn’t a business student in Australia who hasn’t been taught the conventional wisdom of the post-second world war experience that globalised trade brings globalised peace.

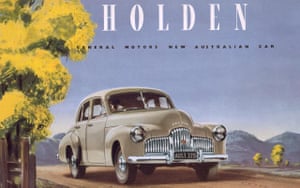

In this scenario, it becomes chilling to examine what items Australians may consider essential but which their country cannot make. That it’s even difficult to find a centralised list of the industries that have closed here reveals the blithe policy approach to domestic manufacturing capacity. But do head to the website of the “Australian Made” campaign and start searching for locally-made consumer goods; the results are startling. It’s hard to believe, but this country once made not only mass-market fridges, washing machines and toasters, but our own computers, televisions and even mobile phones. Before Joe Hockey and Tony Abbott, we made cars. Australia used to make tractors. We mass-produced shoes, and most of our own clothes.

Now, we don’t. Iconic Australian toastie-maker and appliance company Breville may be headquartered locally and do all their design and development here, but their branded products are manufactured in China. Remember Simpson washing machines? Simpson merged with Email, an Australian refrigerator company in the 1980s. By the 1990s, the company was bought and asset-stripped, the appliance brands bought by Swedish multinational Electrolux. Electrolux still make wall-ovens here, but the Simpson/Email factory in Orange, New South Wales was mothballed in 2016; 300 people lost their jobs. The washing machines, along with their other white goods, dropped off the local assembly line years ago.

"Closures and offshoring remain a painful, permanent scar in the living memory of the Australian working class"

And now that we’ve returned to corona-created, increasingly desperate levels of unemployment, we’re obliged to revisit the lost job opportunities that come with Hockey-Abbott style government “industry policy” that allows local factories to shut. Cities and towns across the continent have sad stories of what used to be made in them, but few descriptions of closure resonate with the clarity of Dennis Glover’s essay exploring the decline of Doveton, the industrial suburb of south-east Melbourne where he grew up. In 1970 there were three jobs in its factories for every local family, but by 2015 “just one job for every five families”. Closures and offshoring remain a painful, permanent scar in the living memory of the Australian working class.

Active, intersectional industry policy that mobilises Australia’s considerable education and training capacity could allow us to replicate the success of Germany, a western country that rejected the temptation of cheap offshoring and became an internationally competitive manufacturer by producing goods in which “innovation” is a measurable component.

History shows us that government investment in rebuilding an adaptive and innovative manufacturing base doesn’t just enable that sector to develop and improve. The experience of Germany and Scandinavia have demonstrated that industrial innovation cross-pollinates with enhanced job opportunities and spending, improving the economic performance of sectors in an economy from information technology to education and the arts.

But without proactive industry policy from government, Australia is in a weak position. We’re left without a rapid capacity to respond to crises, such as meeting demands for medical equipment. We’re left without industrial capacity to build our own defence equipment, we’re reliant on the French for submarines. We threaten the supply of things we need to survive in our own homes.

We’re also left denying Australia a powerful opportunity to secure prosperity if we don’t choose to reinvigorate the means for mass employment, continual upskilling and good wages that lifted up Australian living standards for the 50 years that followed the second world war. Manufacturing is the bedrock of a better Australian dream. When we wake up from coronavirus, will we realise it?

• Van Badham is a Guardian Australia columnist

No comments:

Post a Comment